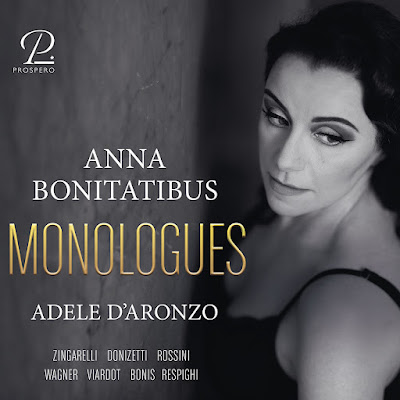

Monologues - Zingarelli, Donizetti, Rossini, Wagner, Viardot, Mel Bonis, Respighi; Anna Bonitatibus, Adele d'Aronzo; Prospero

A terrific disc in which the Italian mezzo casts her net wide for a series of vivid solos, each from a different era, and each providing us with a different voice for a woman addressing us directly

On her new double-disc set, Monologues on Prospero, mezzo-soprano Anna Bonitatibus is joined by pianist Adele d'Aronzo for a programme of dramatic monologues from 1804 to around 1911 with music by Zingarelli, Donizetti, Rossini, Wagner, Viardot, Mel Bonis and Respighi.

The monologue, as a dramatic device, dates back to classical antiquity and here we hear how composers have transferred these ideas to a solo voice and keyboard, into a 'scena drammatica'. Unsurprisingly, many of the subjects and protagonists are classical in their origins - Hero (& Leander), Sappho, Hermione, Arethusa, plus Joan of Arc, Mary Stuart and Salome. But whatever the dramatic origins, there is no doubting the era that the music of each piece belongs to.

Niccolo Zingarelli (1752-1837) was a Neapolitan opera composer. His sojourn in Paris to write Antigone was cut short by the Revolution and he would go on to have posts in Milan, Rome and Naples, ending as Director of the Conservatory. His Ero, based on the story of Hero and Leander, was written between 1804 and 1812, whilst he was based in Rome. It exists in versions with orchestra and with piano (this latter recorded for the first time here). In a sequence of recitatives, arias and ariosi, he explores Ero's state of mind, creating a wonderfully elegant work. Many of the arias are quite short, and the recitatives play an important role. Overall there is quite a classical feel to the piece, and Bonitatibus respects this. She sings with a lovely vibrant sense of line and often quite gentle tone, for all the intensity of the words, the music retains the classicism of composers like Spontini, though that is not to say that there are not virtuoso moments. Bonitatibus and d'Aronzo easily sustain the work's twenty-something-minute duration, never letting it sag.

They follow this with a youthful work by Donizetti, written some ten years after the Zingarelli, though Donizetti (1797-1848) was some 45 years younger. Donizetti was in Naples, where he was writing operas for the Royal theatres. He was thinking of Madamigella Virginia Vasselli, who he would eventually marry, and wrote a cantata for voice and piano, Saffo for her. The author of the words is unknown and may indeed be the composer himself. We begin with an extensive and fluid recitative, certainly not music by rote, and then a substantial aria, 'Come virgine rosa', which from the opening line could not be by anyone else. Here we have the familiar elegant sense of long-breathed melodic line, and Donizetti largely eschews the more elaborate coloratura in favour of chromaticism, leaps and more elegant decoration. As the verses pass by, Donizetti uses these to really intensify the drama.

Rossini was born five years before Donizetti but was successful far earlier in his career than the younger composer. By 1829, Rossini was in Paris, his opera Guillaume Tell was a great success, but the 1830 revolution deprived the composer of the continuation of his contract. This combined with illness seems to have encouraged him to slow down. There were no more operas, but in 1832 he wrote the cantata Giovanna d'Arco. It was almost certainly not performed by Rossini's mistress and later wife, Olympe Pellisier in 1832, but we do know that the cantata was sung by the celebrated singer Marietta Alboni in 1859. This is a relatively unknown piece of mature Rossini, the composer at the height of his powers. The work requires a wide vocal range and great control for the virtuoso moments. Bonitatibus is terrific throughout, conjuring forth some spectacular vocal histrionics yet always making them part of the drama. Despite the bravura moments (of which there are plenty), in Bonitatibus and d'Aronzo's hands this remains a work about Giovanna d'Arco [see my recent review of Bonitatibus' performance of Rossini's Giovanna d'Arco at Wigmore Hall]..

Still in Paris, but now in 1839, a young German composer was trying (unsuccessfully) to make his way up the ladder. Despite a letter of introduction from Meyerbeer, Richard Wagner fails to generate any interest at the Paris Opera for his operas, and he resorts to song-writing and hack work to make ends meet. He writes eight melodies, in French, of which the most ambitious is Les Adieux de Marie Stuart. Less than eight minutes long, it gives us the young Wagner who still idolised Meyerbeer and who wanted to write French opera for French and Italian opera for the Italians. Bonitatibus is finely elegant and makes the piece seem, perhaps, more than it is.

In 1849, Meyerbeer's Le prophète premiered at the Paris Opera, it garnered great success and incited the profound envy of Wagner (who heard a performance in February 1850). The important role of Fidès was created by Pauline Viardot, a great singing actress whose salons became a musical hub and whose compositions, often written for her students, are now coming out of the cold. Her Scene de Hermione was published in 1887 but almost certainly written earlier. It exists in versions for contralto and piano, soprano and piano, and also in an orchestral version, perhaps indicating the importance of the work to Viardot.

It is a seven-minute scene, setting the monologue by Racine. Viardot largely avoids recitative, simply creating a fluid musical flow where one of the influences might seem to be Berlioz (who at one point was considering Viardot for Didon in Les Troyens). It is a rather terrific piece and deserves to be better known.

The composer Mel Bonis (1858-1937), a pupil of Franck and Guiraud, studied at the Conservatoire alongside Debussy, but intense family pressure limited her compositional work. Her danse pour piano, Salome dates from 1909 when she premiered it herself. It reveals an intriguing late-Romantic French voice.

The disc ends with Respighi's poemetto per voce e pianoforte, Aretusa from 1911. Inspired by Shelley's Arethusa, the work sets an Italian text by Robert Ascoli. It exists in versions with piano and with orchestra, and the piano version is recorded here for the first time. It is quite a substantial and dense piano part, and you feel that the orchestral version would be closer to a tone poem with voice. Here, the performers bring out the drama of the work, as d'Aronzo's piano thunders and sparkles, whilst Bonitatibus emotes wonderfully.

This is a terrific disc. Many of the works were written for virtuoso singers with large ranges, all difficulties that Bonitatibus surmounts with apparent ease. Instead, she and d'Aronzo use the music to create real drama. In each work, no matter the musical style, you feel Bonitatibus communicating directly with you, there is a lovely immediacy to the performances. The music on the disc varies between the unusual to the positively unknown, and the performers make a brilliant case for each and in the process have created a terrific recital.

Niccolo Zingarelli (1752-1837) - Ero (1804-1812) [24.19]

Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848) - Saffo (1824) [9.23]

Giocchino Rossini (1792-1868) - Giovanna d'Arco (1832) [17.01]

Richard Wagner (1813-1883) - Les Adieux de Marie Stuart (1840) [7:46]

Pauline Viardot (1821-1910) - Scene d'Hermione (1887) [6:53]

Mel Bonis (1858-1937) - Salome (1909) [4:41]

Ottorini Respighi (1879-1936) - Aretus (1911) [11:53]

Anna Bonitatibus (mezzo-soprano)

Adele d'Aronzo (piano)

Recorded 20 August, 15 November 2021, 24 January, 28 February 2022, Griffa & Figli Srl, Milano, Italy

PROSPERO PROSPO068 2CDs [50:45, 31:14]

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Steeping listeners in Indian classical music without them knowing it: sitar player Jasdeep Singh Degun on his new disc, Anomaly, working on Opera North's Orpheus and more - feature

- Then I play'd upon the Harpsichord: Ensemble Hesperi's engaging look at the musical life of Queen Charlotte - video review

- A love of telling stories: Norwegian composer Bjørn Morten Christophersen on setting Charles Darwin's 'On the Origin of Species' to music - interview

- Finding his way: Opera Rara's revival of Donizetti's relatively early L'esule di Roma showed a composer finding his own voice - opera review

- Giovanni Legrenzi: Rinaldo Alessandrini and Concerto Italiano explore motets by one of Venice's most prominent composers - record review

- The Library of a Prussian Princess: Ensemble Augelletti at the Newbury Spring Festival - concert review

- Meditating, listening & letting the music unfold: Syrian composer & musician Maya Youssef on the inspirations behind her music - interview

- Cautionary Tales: the current cohort of Young Artists from the National Opera Studio in an evening of contemporary opera - opera review

- Temple Song: Kate Royal, Christine Rice & Julius Drake in Brahms, Schumann and Weill - concert review

- Silence, texture and atmosphere: music by John Luther Adams, Kaija Saariaho, Judith Weir, and Gary Carpenter at Royal Academy of Music's Fragile Festival - concert review

- Casta Diva: trumpeter Matilda Lloyd showing just what her instrument can do with elegant yet dazzling accounts of Italian bel canto arias - concert & record review

- Home

%20Bill%20Smith_Norwich%20Cathedral.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment