|

| The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1991-91 (replica of 1915-23 original) Moderna Museet, Stockholm |

The Bride and the Bachelors: Duchamp with Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns (Barbican Art Gallery 14 February - 9 June 2013) is an exhibition about the exchange of ideas across art-forms. It attempts to articulate the complex web of influence, friendship and artistic sharing that arose between the French artist Marcel Duchamp, responsible for a remarkable, revolutionary body of work up to 1923, and the American artistic constellation of John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns from the 1940's onwards.

Duchamp remains an elusive figure, starting out working mainly in paint, he worked extensively on his sculpture/painting The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, before abandoning painting and producing a series of ready-mades, which questioned the very nature of art, then finally in 1923 he abandoned art entirely and devoted the remainder of his life to chess.

The American artists, who collaborated and exchanged ideas from the 1940's onwards, created a body of work which helped redefine what 20th century art was. Whilst Cage and Cunningham are still linked in our consciousness, we tend to see the works of Johns and Rauschenberg as separate entities, but the four artists were close collaborators. And the links to the work of Duchamp are remarkable, links both artistic and personal.

But it is the way that the ideas of Duchamp chimed in with and pre-figured the work of these artists that is the remarkable heard to this exhibition. The questioning of the role of the artist, the use of chance, the blurring of the distinctions between art and life.

The difficulty the exhibition has is that it is trying to convey to us, at many years removed, the burning excitement of an idea, the intensity of sharing where artistic personalities become mixed and life becomes art, or vice versa.

It does not help that two of the art forms involved are evanescent. To combat this the exhibition has a programme of dance events based on the work of Merce Cunningham. And composer Philippe Parreno has arranged an aural backdrop which uses works by Cage, himself, Duchamp and others. Yes, another correspondence Duchamp produced some chance based music works well before Cage.

The art gallery is painted white, of course. The lower level is divided into two sections, the first is devoted to Duchamp's enigmatic masterwork, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even though what we see is not the original but a copy from the 1990's. Around it are a number of Duchamp's paintings including Nude descending a staircase but also The Fountain perhaps his most infamous ready-made.

|

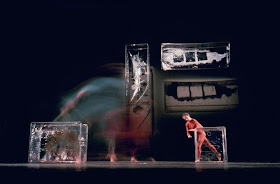

| Walkaround Time (1968) Choreography: Merce Cunningham and stage set and costumes: Jasper Johns (c) 1972 by James Klosty |

The remainder of the downstairs gallery is given over to a performance space surrounded by sets by Johns and Rauschenberg for Cunningham's works - the plastic boxes covered with images taken from Duchamp's Bride, and serried ranks of seats and bicycle wheels which also pay homage to another Duchamp ready made. Though we had live dance whilst I was there, what I would dearly have loved was some video images of the total concept filmed at the time.

The upstairs galleries explore themes, showing how Duchamp's ideas influenced the younger men. This influence stretches through time so that the time-span of works in the exhibition is quite wide ranging. If someone came to this exhibition knowing mainly the more recent works of Johns and Rauschenberg, then I would be very interested in what they thought of the new perspectives the exhibition brings.

Here sound is made visual, some of Cage's wonderfully graphic looks scores can be heard playing on a player pianos in the lower gallery and there are Duchamp's earlier efforts there for comparison. Some of Cage's scores extend our concept of what music is (and what performance is), just as Duchamp had challenged and extended our view of visual art. A further link between these two is chess, which subject gets a gallery all of its own. The idea of ready-mades is common to both Duchamp and to the work of Johns and Rauschenberg, and another gallery looks at these. There is also a picture of Duchamp, by Man-Ray, dressed as his female alter-ego in the guise of La Belle Haleine (another tricksy bith of the Duchamp persona which ties in with the rest with difficulty).

The gallery on Dance Collaborations includes not only Rauschenberg sets for Cunningham, but Johns paintings Dancers on a Plane which mimic the movement of Cunningham's dancers. Alongside these Cage's notes for scores commissioned for Cunningham's dance pieces. Cunningham's working methods were distinctive, his collaborators knew very little about the detail of the finished work, with music, set, costumes and dance sharing the stage for the first time during the premiere.

A busy gallery space is perhaps not the best place to encounter Merce Cunningham's work, but the young dancers who were performing impressed me. Choreography is an enigmatic art, it is hard to discern how it links with other works of art. Elsewhere we can trace the complex interrelationships, with Cunningham's choreography we music work hard to pick up the excitement of original creation.

Some of the works on display are profoundly beautiful, many are patently fragile, and quite a few have travelled far. So we must be grateful for the opportunity to be able to experience them together like this. Two things worried me. Though there was discussion of the use of the I Ching by Cage and Cunningham, the wider influence of Zen (which became particularly important to Cage) was not explored at all (Kay Larson in her book on the composer has a lot to say on this topic, including the influence of Duchamp). And perhaps more important, the rather intense web of personal relationships and their influence on the creative impulse is hardly mentioned at all. There may be more coverage in the catalogue, but the information in the gallery was at a very impersonal level. We never learn who these people were and why they created this fascinating art. Would it be obvious to an outsider viewing the exhibition that Cage and Cunningham were lovers as were Johns and Rauschenberg.

Ultimately I found the exhibition fascinating, but rather too intellectual. It evoked connections and presented us with a network of influences and artistic collaborations, but in a rather cool way which did not quite bring out the people or the passion underneath.

- Medea music - feature article

- I fagiolini - concert review

- Getting it Right 2013 - conference report

- Love Abide - Roxanna Panufnik - CD review

- Drama Queens - Joyce DiDonato at Barbican Hall

- Shakespeare Songs - Nicky Spence - CD review

- Great sets, shame about the opera - Montemezzi's Nave

- Alex Esposito at Rosenblatt Recitals

- La Traviata - Peter Konwitschny - ENO

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment