|

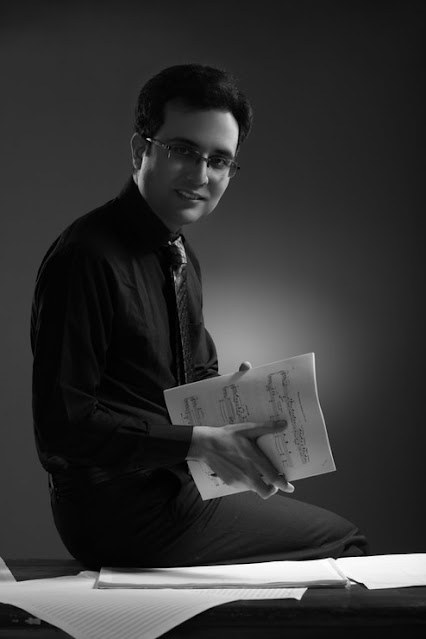

| Farhad Poupel |

Farhad writes music in the Western classical tradition, and I was interested to find out how Iranian he considered his music to be. He does not write music using traditional improvisation and quarter-tone scales, but that is to give a rather limited definition of Iranian music. There is a rich Persian culture to draw on and he feels that his music is Iranian in the sense that when he plays his music for Iranians, to them it sounds Iranian. He uses structural elements from Iranian music, his cadences often have an Iranian style to them, he uses the major third rather a lot and writes cadences based on the submediant (sixth degree) rather than the dominant (fifth degree). But he tries to be himself when he writes music, and he mostly listens to Western classical music.

Farhad grew up in quite a diverse musical environment. His childhood memories of music all come from the cinema, American music, and from Persian pop music. After the Revolution, most Persian pop artists went to the USA and their music was shared in Iran via cassettes recorded in the USA. Farhad studied Persian classical music, whilst his mother played the piano and had lots of recordings. Farhad grew up open to everything.

His 2019 work, Childhood Memories (Persian Suite) which premieres in 2022 in the USA, is based on Persian folklore. He has always been interested in Persian literature, and he mentions Matthew Arnold's poem, Sohrab and Rustum which is based on a story from the Persian Book of Kings. The book preserves Persian culture after the rise of Islam, preserving the Persian identity. And after the recent political upheavals in the country, people used characters from the Book of Kings as symbols. Farhad's 2020 work for piano and orchestra, the Legend of Bijan and Manijeh, which premieres in Canada in November 2022, uses a lot of characters from the Book of Kings. Another of Farhad's recent works, Kaveh the Blacksmith, is based on another character from the book who shows resistance to tyranny. His new piano concerto, with Peter Jablonski as soloist, The Seven Labours of Rustam is also based on characters from the Book of Kings. But Farhad is also planning a children's opera based on a Swedish story.

In Iran, his underlying passion was for Western classical music, and he studied composition for five years, even though this required a journey of six hours in each direction. But the Iranian government is very anti-art and classical music needs to be propagandist and popular, dumbed down. There is a Western classical orchestra and many performers, but the government works against it, and it is difficult with one professional orchestra and just one or two venues. All this makes for a very complicated background, but he has never tried to break his contacts with the country.

He has never used traditional instruments, but he is open to using them though his main interest is Western classical music. His music often takes a story as inspiration, and even when it doesn't the story can be there. He wrote a work for violin and piano for Bradley Creswick and Margaret Fingerhut (to be performed in November 2022) which Farhad was going to call it a sonata for violin and piano, but in the end, he decided on the title, Dance of the Butterfly and Flame. Fingerhut commented that his work has a narrative sense to it, and he usually sees music with an underlying narrative structure.

|

| Farhad Poupel and pianist Peter Jablonski |

He became a composer because he simply could not stop writing music. A memorable moment was when he heard Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 16 when he was around 13 and it blew his mind. He wrote a classical rondo after this and though he studied the piano, he continued composing. However, this was not his main focus of study, he has a Pharm D in pharmaceutical science. When he was 23, whilst he was studying pharmaceutical science, he went to Saeed Sharifian's class, and it just clicked; he realised he wanted to be a composer. Whilst in Iran, he needed to make an income from something other than music and he was a part-time pharmacist (few if any composers in Iran make a living from composition). He also studied by himself, he had internet access to scores and read books, either in the original language or translated into Persian from Russian and French.

When I ask about influences, he comments that if I had asked the question two years ago his answer would have been Ralph Vaughan Williams, but now his influences spread wider including Ravel, Sibelius, John Adams and Jonathan Dove. English music has always been a big influence on him, though this is gradually becoming less. Saeed Sharifian was, of course, very influential when Farhad was studying, especially Sharifian's free attitude to Persian music, and his not trying to be Persian. Farhad and Sharifian had lots of disagreements, but Farhad feels that this shows how good a teacher Sharifian was, encouraging Farhad to be independent. Older composers who are heroes include Dvorak, for the sense that you don't have to be miserable to be a great composer, and Britten, for his attitude, independence and high standards whilst trying to reach both ordinary people and connoisseurs. And Farhad adds that the distinction between these is very idiotic.

He is looking forward to the premieres of Kaveh the Blacksmith for brass and percussion, and Persian Love for mezzo-soprano and piano, and he is writing a new piano trio, Prelude and Demonic Waltz.

- Margaret Fingerhut (piano) and Bradley Creswick (violin) give the premiere of Dance of the Butterfly and the Flame at Sage Gateshead (12/11/22)

- Portland Youth Philharmonic, conductor David Hattner give the premiere of Childhood Memories Persian Suite in Portland, Oregon (12/1/22)

- Windsor Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, pianist Jeffrey Biegel, and conductor Robert Franz give the premiere of the Legend of Bijan and Manijeh in Windsor, Ontario (19 & 20/11/22), and the work gets its USA premiere in Feb 2024

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- An evening of story-telling: soprano Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha & pianist Simon Lepper at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- Highly persuasive: pianist Iyad Sughayer in Aram Khachaturian's Piano Concerto and Concerto-Rhapsody - record review

- Music, merriment and mayhem: a day at the Oxford Lieder Festival - concert review

- Coleridge-Taylor & Friends: Elizabeth Llewellyn and Simon Lepper at the Oxford Lieder Festival - concert review

- Serenade to Music: Nash Ensemble and a fine array of soloists celebrate Vaughan Williams' 150th birthday - concert review

- Doing it with the requisite seriousness is key: composer Noah Max & director Guido Martin-Brandis on bringing Holocaust story, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas to the operatic stage - interview

- Up close and personal with Farinelli: A Queer Georgian Social Season at Burgh House - concert review

- The Roadside Fire: Ossian Huskinson & Matthew Fletcher in Vaughan Williams and more on Linn Records - record review

- A question of transcendence: conductor Simone Menezes' Metanoia project - interview

- A new benchmark: the first new recording of Tippett's The Midsummer Marriage for over 50 years brings out all the work's intoxicating brilliance - record review

- Composers' Academy: new works from Hollie Harding, Joel Järventausta & Jocelyn Campbell with Philharmonia Orchestra & Patrick Bailey on NMC Recording - record review

- A tremendous achievement: Handel's Tamerlano from English Touring Opera in performance that really drew you into the drama - opera review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment