|

| Meyerbeer: Le prophète - Deutsche Oper Berlin(Photo Bettina Stöß) |

In fact, it seemed a year for rarities because New Sussex Opera gave the first performances of Stanford's The Travelling Companion since the 1920s, and further back in time I caught Haydn's Armida in his former place of work, Schloss Esterházy. Early Verdi came up trumps too with I Lombardi in Heidenheim, and Alzira in Stephen Barlow's swansong season at Buxton. Whilst at Glyndebourne, Barber's Vanessa was finally brought in from the cold. And in the concert hall, Martyn Brabbins heroically stood in at the last minute for a rare performance of Ethel Smyth's mass with BBC forces at the Barbican, whilst Ruth heard Opera Rara in the original version of Puccini's first opera, Le Willis.

It was also a year for French grand opera, not only the Meyerbeer (who virtually invented the genre), but Verdi's Don Carlos in French and in the original 1867 version in Lyons, and in Italian in the later 1884 version in an intimate setting from Fulham Opera. And in The Hague, Opera2Day presented a radical new version of Ambrose Thomas' Hamlet.

New operas included Alex Mills' striking piece based on the work of Marie Stopes and premiered at the Wellcome Collection, and David Sawer's The Skating Rink at Garsington, not to forget George Benjamin's Lessons in Love and Violence at Covent Garden.

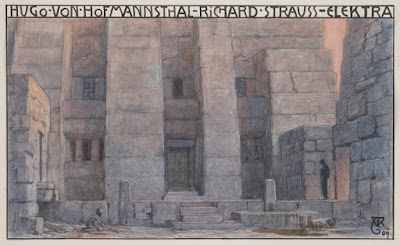

It was a strong year at Opera Holland Park both on the main stage, which included the company's first Richard Strauss, and with the Young Artists performance. Chelsea Opera Group gave us a world-class performance of Bellini's Norma.

The Dunedin Consort showed that Bach's Mass in B minor has terrific power when performed on a smaller scale and Adam Fischer opened Kings Place's 2018 season with a joyous small-scale account of The Creation. In song, it was a good year for Schubert with terrific performances from Robin Tritschler and from Gerald Finley.

Below, Anthony, Ruth, Tony and I have all made our selections from 2018's memorable performances.