|

| Vincent Larderet (Photo Karis Kennedy) |

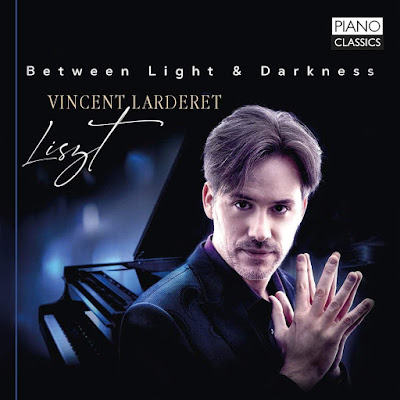

The French pianist Vincent Larderet's most recent discs have involved the music of his countrymen, notably a pair of discs of the music of Maurice Ravel. But for his latest recording he has turned to a rather different composer, Franz Liszt, and Vincent's recital, Between Light and Darkness on Piano Classics pairs some of Liszt's larger-scale mature works such as Après une Lecture de Dante and Ballade no. 2 with a selection of the more enigmatic late pieces. I spoke to Vincent by Zoom to find out more about the thinking behind the programme. Vincent is someone who thinks deeply about the music he is playing and the programmes he is constructing, and in person (or via Zoom) he is a charming conversationalist so that the results were a lively and thought-provoking hour.

|

| Earliest known photograph of Liszt (1843) |

Regarding interpretation, Vincent describes himself as something of a perfectionist, he wants to take this time to develop his interpretation. He comments that performers are interpreters but not geniuses like the composer, so need time to think to get involved with the work's natural language. In an ideal situation, Vincent would practice a work, play it, put it on one side and repeat the process, each time his interpretation develops maturity, and then finally record. It is, he admits, a long process but one during which there is the possibility of reaching the meaning of the work and playing it at the highest level. He also admits that it is possible to play a work in a few months, but this is not a good strategy for him.

Whilst there are thematic links between the works on the recording relating to the light and darkness of the title, Vincent also wanted to put the great masterpieces alongside the shorter, late works which are more abstract, and Vincent found it fascinating to confront the two styles.

Our first image of Liszt is as the great virtuoso who invented the piano recital as a genre, but this is only one part of a multi-faceted composer, and Vincent sees in the late works a composer stripped of all artificiality. Thus the programme features a series of mirrored dualities, not just dark and light, but romanticism and aesthetic abstraction, passion and despair, sentimentality and religious mysticism.

Our image of Liszt the virtuoso is the composer in the first part of his life, lauded and feted, very much the modern-style superstar. This is important, but Vincent points out that the composer finished his life alone and separate, an Abbé in prayer. This religious mysticism is apparent in his oratorios Christus (1862-1866) and The Legend of St Elizabeth (1857-1862), but for Vincent, you can also find it in the instrumental music. There is a mournful quality to the late piano works, a very poetic quality. But they are difficult works for the audience, abstract and extremely introverted. Vincent describes it as futuristic music, the harmony is very dissonant and some pieces, such as Nuages Gris (which was written in 1881 but only published in 1927) have no tonality. Even Liszt when he was writing it seemed conscious that it as the music of the future. So we have an entirely different facet of Liszt, the visionary innovator.

As the late works are not played very often, Vincent was keen to programme them. Too often, he comments they are added almost as an addendum to sets of Liszt's piano music but Vincent wanted to approach them in a new way, to bring out the contrast between the orchestral piano writing in the earlier works and the abstract, near minimalism in the late works. So the austere and mournful late works form a mirror to their complete opposite, the early works such as the Hungarian Rhapsodies, the opera fantasies, the transcendental studies.

|

| Vincent Larderet performing in Germany, 2013 (Photo Martin Teschner) |

We start to consider La lugubre gondola (1883) but first Vincent comments on the title being in French. Whilst Liszt spoke French, German, Italian, German and Hungarian, it was French that he used regularly and he was very influenced by French poetry. When considering the music of La lugubre gondola, Liszt uses the marking piangendo which means crying out. The work itself is austere, there are not many notes, but the expression is very intense, sometimes Liszt uses just the right hand alone like a recitative. For Vincent, it is completely amazing music, and when choosing the late works for the disc, Vincent chose the ones he loves, the ones he finds eloquent and futuristic.

The title, Between Light & Darkness, is also a reference to Liszt's religiousness, with light symbolising paradise for Christians, and the dark, hell and the devil. By the time he came to write these late works, Liszt had suffered; he lost his son Daniel in 1859 and daughter Blandine in 1862, and he took refuge in religion to deal with the suffering (in the monastery Madonna del Rosario, just outside Rome) and was ordained in four minor orders, becoming known as Abbé Liszt. And whilst there is not that much light in the programme, Vincent points out that you can find it even in terrible works like Funérailles (written 1849).

In a work like La Notte (performed in its final version of 1866) there is the musical illustration of death whilst the Après une Lecture de Dante (written 1849, inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy) includes a musical illustration of hell and death, it even begins with a tritone, the diabolus in musica, the devil in music. This is why we call it programme music.

|

| Liszt in March 1886, four months before his death, photographed by Nadar |

But Liszt's virtuosity is interesting as well, after all, he revolutionised pianistic technique. Chopin, for Vincent, is a very classically-inspired composer and Schumann is very romantic, inspired by Beethoven and Mendelssohn, whereas Liszt's piano music with its almost orchestral texture is closer to Brahms' piano writing. Vincent goes on to tell the story of Liszt going to see Brahms, who fell asleep during Liszt's performance of his B minor Sonata.

Virtuosity for its own sake, for Vincent, is of no interest, except perhaps for music written just for the left hand, which is always a challenge. But he then asks me to consider what is the virtuosic, technical aspect to Liszt? In all the virtuoso music there is always meaning so that in the operatic paraphrases virtuosity is a means of serving the lyricism of the opera.

Of more interest to Vincent are other technical aspects to playing Liszt, such as the sound. Liszt's creation of an orchestral sound in the piano means the player needs lots of colours, it is important for the player and the audience to imagine both orchestral power and the range of orchestral colours. This is the sort of challenge which appeals to Vincent.

La Notte, which is effectively ten minutes of mournful music, presents a different sort of technical difficulty, so that technical difficulty is certainly not simply coping with lots of notes. Vincent points out the Mozart remains one of the most difficult composers, the purity of his music makes it so if you put a finger wrong it can be catastrophic. And playing legato on the piano is another highly technical challenge.

|

| Vincent Larderet with conductor Daniel Kawka (Photo Thierry Kawka) |

Looking at Vincent's biography, he has quite a wide repertoire. As a Frenchman, he feels connected to French music in his soul, but in fact, this did not come naturally. During his studies, he played a wide variety of repertoire and his teacher never focused specifically on French music. After his studies, his first focus was Romanticism, the music of Beethoven, Brahms, Liszt, Schumann, Chopin, and then late Romanticism including the music of Russian composers such as Scriabin and Rachmaninov. But with maturity and the passing of the years, he felt that he could focus on French music more.

At this time he wanted to do a disc of Szymanowski's music but the record company refused, they would prefer a Polish pianist to play the composer. Instead, he was offered a disc of music by the French composer Florent Schmitt (1870-1958). Like many people, Vincent knew Schmitt's orchestral works such as La tragédie de Salome but was unfamiliar with his piano music. He comments that he finds that when it comes to music history, the French are not particularly interested in exploring their own music beyond the well-known composers so that performances in France of music by composers such as Honegger and Roussel are rare.

From Schmitt, Vincent started to further explore French impressionism in music, and was amazed at this new conception of piano writing and decided to focus on the music. In a way, it is surprising that it took him such a time to reach this point, as his teaching came in a direct line from Ravel. Vincent's teacher was a pupil of the Lithuanian-born French pianist Vlado Perlemuter (1904-2002) who was a student of Ravel's from 1927 to 1929 when he studied all the composer's piano music. In fact, the 19-year-old Vincent met Perlemuter at a competition but did not realise the senior pianist's direct connection to Ravel. Looking at Perlemuter's scores of Ravel's music, there are no notes from the composer but Perlemuter notes down what Ravel says, and Vincent describes Ravel's comments as being very detailed and exigent.

When Vincent recorded discs of Ravel's music, his reputation grew. And he admits that since playing French music regularly, his technique has improved as he finds French music so very detailed, refined and exigent.

Looking ahead, he has plans for recording music by Scriabin and would like to extend his exploration of Ravel's music to include the complete piano works though plans for this are not firm. When discussing his recordings, Vincent comments that recordings are like photographs, a moment captured, and that if he played the pieces now, details would be different.

|

| Vincent Larderet performing Ravel's Piano Concerto for the left hand at La Roque d’Anthéron 35th international festival, 2015 (Photo Christophe Grémiot) |

Vincent's father was a musicologist, so Vincent grew up in a musical family with access to books and recordings. He started to play without having lessons, but his first impulse was to be a composer. His father was supportive but demanding, and Vincent did progress somewhat. At the conservatoire, he studied both piano and composition, but regarding this latter, he was told that though he was talented, more study was needed. Vincent decided that studying counterpoint was boring, he would concentrate on something else.

In fact, besides music, there had been another possible strand to Vincent's career. Throughout his youth, he had drawn cartoons and won a European prize when he was 13, but he now admits that his two sons are far more talented at this than he ever was.

In the end, Vincent decided to concentrate on the piano but he doesn't like the name pianist and prefers musician which is as much a philosophy or religion. For Vincent, the piano is a means to serve the composer, and this means respecting the detail of the text. As an example, Vincent mentions Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, which he is revisiting for a future concert. Looking at the score and listening to performances, Vincent comments that the second theme is marked piu lento and most pianists play it at the same tempo as the first theme, yet it is not written like that.

Whilst he does not want to be too strict or a puritan, for Vincent the performer is only a mirror and should serve the text and the composer. Vincent's approach involves not just the text, but understanding why it was written like that and what is the meaning. And all the parameters of your playing depend on the work, so the Vincent uses a different sound for the music of Prokofiev, Debussy or Ravel, and not just sound but a different aesthetic and colour, there will be more rubato in Debussy than Ravel.

Vincent isn't interested in narcissism, he just wants to understand the meaning of the score. Each performer has their particular sound, their soul, and expresses their own feelings inside the music. Perhaps his approach seems intellectual, he says of himself that he is intellectual yet intuitive. But he is not a puritan and is interested in the soul of the music, to communicate with the audience.

When I ask about his heroes, he mentions the composers Ravel and Liszt. For pianists, he first mentions Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and Claudio Arrau, two of the greatest musical technicians, and adds Emil Gillels. Regarding conductors, he mentions Carlo Maria Giulini and Sergiu Celibidache, plus Herbert von Karajan before 1970.

At home he listens to more orchestral music than piano, and he is

something of an audiophile. He has a big sound system, and a collection

of LPs which numbers over 2000, concentrating on Columbia and Decca from

the 1960s.

- Between Light and Darkenss - Liszt - Vincent Larderet - Piano Classics, available from Amazon,

- Debussy Centenary - Vincent Larderet - ARS Produktion, available from Amazon,

- Brahms, Berg - Vincent Larderet - ARS Produktion - available from Amazon,

- Ravel: Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, Schmitt: J’entends dans le lointain… - Vincent Larderet, Ose Symphonic Orchestra, Daniel Kawka - ARS Produktion, available from Amazon,

- Ravel - Vincent Larderet - ARS Produktion, available from Amazon,

- Schmitt piano music - Vincent Larderet - Naxos, available from Amazon,

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

- Donizetti on the cusp: never a success in his lifetime, Opera Rara reveals much to enjoy in the composer's 1829 opera Il Paria - CD review

- A beguiling disc: Aberdene 1662

from Maria Valdmaa & Mikko Perkola on ERP explores songs from the

only book of secular music published in Scotland in the 17th century - CD review

- Virtuosity and Protest: Frederic Rzewski's Songs of Insurrection receives its first recording - CD review

- Re-inventing Kurt Weill: How

Lotte Lenya's performances of her husband's music in the 1950s, born of

expediency, came to define how the songs were performed - feature article

- Mysteries: Luxembourg-born

pianist Sabine Weyer on how combining music by a Soviet Russian

composer and contemporary French one made a satisfying new disc - Interview

- The missing link: romances by Alexander Dargomyzhshky, a friend of Glinka and an influence on a later generation of Russian composers - CD review

- If Haydn went to Scotland: the Maxwell Quartet continues its exploration of Haydn's London quartets alongside 18th century Scots traditional tunes - CD review

- A surprisingly complex work: Puccini's late Verismo classic, Il Tabarro, in a new studio recording from Dresden - CD review

- Dowland transmuted: Time Stands Still from Portuguese composer Nuno Côrte-Real - CD review

- The pocket watch and the news periodical: how the public concert developed in 17th and 18th century London - feature article

- Researching the mathematics of emotions: composer Arash Safaian on his recent fantasy about Beethoven's music, This is (Not) Beethoven - interview

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment