.jpg) |

| Christine Plubeau, Violaine Cochard & Reginald Mobley at the Bayreuth Baroque Opera Festival in September 2023 (Photo Bayreuth.Media) |

We caught American countertenor Reginald Mobley in recital at the Bayreuth Baroque Opera Festival in September [see my review], when he performed a programme of music by Purcell, Handel and Ignatius Sancho, a former slave who in the 18th century became the first known British African to have voted in Britain. Reginald will be returning to Sancho's music in 2024 as part of his project Sons of England with the Academy of Ancient Music. Reginald became the first-ever programming consultant for the Handel & Haydn Society following several years of leading its community engagement Every Voice concerts. He also holds the position of Visiting Artist for Diversity Outreach with the Baroque ensemble Apollo’s Fire and is also leading a research project supported by the UK's Arts and Humanities Research Council to uncover music by composers from diverse backgrounds (of which his Sons of England is a part). I caught up with Reginald last month when we chatted about Ignatius Sancho and the wider subject of the importance of diversity in music, as well as spirituals and how there is still a conversation to be had around the performance of them.

|

| Reginald Mobley |

Reginald has been working with the Boston (USA) based Handel & Haydn Society (founded in 1815 and the longest-serving such performing arts organization in the USA) as programming consultant, helping to expand and diversify the repertoire. With Harry Christophers, the Handel & Haydn Society's artistic director until 2022, Reginald commissioned Jonathan Woody’s Suite for Orchestra, a suite of dances based on Sancho's music, which the orchestra recorded during the Pandemic. Reginald did a similar project in September 2022 at The Juilliard School when violinist Rachel Podger directed a Suite of Dances and Songs, arranged by Nicola Canzano. Reginald loves the idea of capping a programme with some music by Ignatius Sancho, as it gives audiences a way to understand the diversity of places like 18th-century London.

Born in Florida and brought up singing jazz and gospel, Reginald doesn't just perform 17th and 18th-century classical music. At that Bayreuth concert, he rounded things off with a wonderful performance of a song by Duke Ellington. His debut album, Because, on Alpha Classics [see my review] featured a partnership with jazz pianist/composer Baptiste Trotignon performing spirituals and gospel in a style that deliberately sat between classical and jazz. The fact that the disc isn't strictly classical or jazz was just the point, and it proved both easy and difficult for people to deal with. When Reginald and Baptiste Trotignon did a concert tour to launch the disc, the opening concert was in Paris at Le Bal Blomet, the oldest jazz club in Europe where Josephine Baker had performed, and the next concert was at the National Centre for Early Music in York.

Part of Reginald's point is that spirituals are early music. The Atlantic slave trade began in the 17th century and by the 1690s, the English were shipping the most slaves from West Africa. When Handel was writing his music in London, Reginald's ancestors were working in the slave fields and singing the music that we came to know as spirituals.

Of course, the performance of spirituals is an issue freighted with significance. Reginald comments that he wears a passport on his skin, he sings them from first-hand experience. But he also feels that this music should be shared and that though there is something of a stigma around non-Blacks and non-Americans singing this music, we should share it. This means that we need a conversation, particularly in the English-speaking countries that were involved in the slave trade, about the issue, and resolve the sense of disenfranchisement. He admits that there is still a lot of anger in the air around the issue, but it is not from want of trying to achieve dialogue and he points to the way Dvorak in the USA in the 1890s was so inspired by spirituals, that he heard by way of the collecting of Harry Burleigh.

There is something here that still needs exploring, and Reginald points out that other musics that have their origins in slavery and the slave trade, such as barbershop, blues, rock and so on, are widely shared without any problem. So, when are we going to break the veil that complicates the issue around spirituals, after all, that is what musicians are for.

|

| Reginald Mobley performing with Baptiste Trotignon in June 2023 |

One of the things that Reginald picked me up on during our discussions was not simply conflating diversity with Black composers. For Reginald, diversity means casting the net around Black, Queer, Women, Latino and Hispanic artists. There are plenty of such composers in the historical record, including Vincente Lusitano (16th century), Ignatius Sancho and Chevalier de St Georges (18th century), Esteban Salas y Castro (in 18th century Cuba), African-American songwriter James Bland (19th century), Samuel Coleridge Taylor, and many more.

Casting the net so widely can make things difficult, but it is worth it. We need to grasp these composers and their music to understand society and their place in it. We must accept that the world is awake now and we need to show that this music is important, it is not just about dead white Germans. People that look like you and me are part of it. When introducing the work of Ignatius Sancho at the Bayreuth concert, Reginald explained to the audience that he felt it was important to share the work of someone, amongst all those great musicians, who happened to look like him.

Not every historical circumstance was good, you only have to think of Slavery, and the Spanish colonisation of South America, but throughout all these events, music spread. Music knows no borders - the lute is based on the Arabic oud, and the sarabande was originally a Central American dance. And music can be heard by everyone, it cannot be owned. As such, it is a very equalising art form, there is no way of owning sound. Performing music allows sharing ideas in a way that cannot be done simply through words. This is the magic of music, and we don't always tap into this.

Reginald has found that people are generally receptive to his ideas, but he adds that a lot of the work is being done behind the scenes by the very things that prove we need such diversity. The deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, for instance, proved that there was still a lot of work to be done. People approached him and other people of colour, the deaths caused a moment of reflection, making people consider what needed to be done to fix things. The arts wanted to be seen as a safe haven for people of colour and understood work was required to achieve this. These sorts of events made it possible for him to get a foot in the door.

And of course, Reginald arrives carrying two flags, Black Lives Matter, and the Rainbow Flag.

|

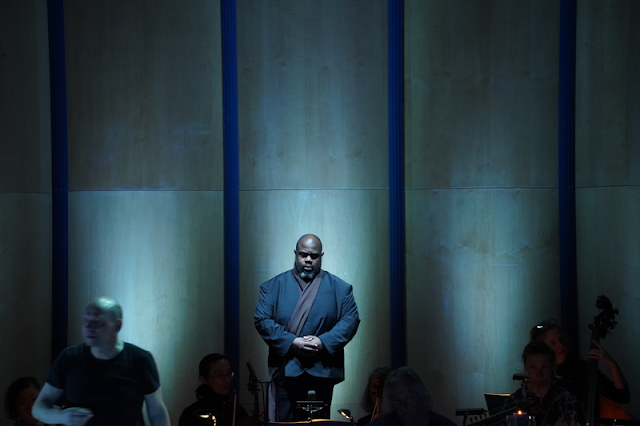

| Reginald Mobley as Christus with SingFest Choral Academy Hong Kong & lautten compagney BERLIN in Bach's St John Passion at the Thuringia Bach Festival |

He points out that the arts still have some way to go before they are fully accepting of Queer and Trans composers, this is particularly true of composers who were active before the social construct of homosexuality. For instance, we know from Ellen Harris' work that significant parts of Handel's life were spent in a queer sphere, though at the time the idea of a homosexual or a gay man did not exist.

Reginald feels that all this is about representation. Whether we are talking about a young person of colour or a young queer person, it is about seeing that someone who looks like you has always been here. Straight white men just don't need to think about the issue of representation in the same way, they are already part of the narrative.

At the Queer Arts Festival in Vancouver, Reginald gave a recital with Early Music Vancouver entitled A Queen’s Music that explored just some of these issues, presenting music by composers who existed before the social construct of homosexuality was created but whose lives can be seen as in some way queer. We existed before there was a name for us, and it is important that we speak out. However, Reginald's approach to diversity is not one of quotas and box ticking. His whole desire is freedom, the freedom to find and explore this music if it appeals.

Reginald was born and grew up in Gainsville, Florida and the music of his childhood was gospel and jazz; as a boy, he sang at the Seventh-day Adventist Church. In the sixth grade, in Middle School, he heard a Bach fugue played by the school's concert band and this started a life-long obsession, even though he was told by people including his family that this wasn't his music. He feels it important that whatever their background, people should not feel this societal block.

His decision to study music was a relatively late one. In his senior year in High School, he sang classical music in a choir for the first time, and he saw the Three Tenors on television and wanted to do that. He went to college to study tenor, but it was never easy for him to do and then his voice professor heard him singing barbershop where Reginald sang the top line which is usually called tenor but is in the alto range. The professor made Reginald sing to him in that range. Reginald had no idea of the countertenor voice but found the experience liberating so that what he heard and felt inside of himself could be opened out and let out. But he made no stylistic changes, he performed the same range of music as a countertenor - gospel, spirituals, jazz, musical theatre as well as classical. His professor insisted that everything that comes out of you is your voice, and this is the creed by which Reginal lives. Whether you hear him in Purcell, Handel or Duke Ellington, he is always Reginald Mobley.

As he started by singing jazz and gospel before he even discovered his countertenor voice, he always returns to these and he feel that it keeps him honest, this music is an instinctual thing, reflecting how he processes and moves through life. He reiterates that though style and genre might change, it is important that he remain himself. He regards this as the ultimate gift as a singer, to be vulnerable, to show yourself as you are. People are more willing to trust you when you are being honest.

During October 2023 he joined the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists, conductor Dinis Sousa, for Bach's Mass in B Minor in Chicago, New York, Princeton, and Ottowa (Canada). Then looking ahead he has plenty of Messiah performances coming up. In 2022, he performed as Christus with SingFest Choral Academy Hong Kong and lautten compagney BERLIN in a staging of Bach's St John Passion at the Thuringia Bach Festival, and they are mounting it again in Hong Kong next year. Reginald describes is as an incredible show and the original performance is available on Vimeo.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on thisblog

- An evening of wit, delight and magic: Silent Slapsticks at The Ritzy with Brixton Chamber Orchestra - film review

- The level of polish & perfection is remarkable: Apollo5's Haven - record review

- Engaging & involving: Christophe Rousset & Les Talens Lyriques release Thésée as their 12th Lully opera album - record review

- Two Cities: Ned Rorem in Paris & New York - centenary celebrations at London Song Festival - concert review

- Exploring his musical roots: conductor Duncan Ward chats about his jazz-inspired, Eastern European & French music coming up with the London Symphony Orchestra - interview

- Piatti Quartet launches its Rush Hour Lates at Kings Place with Dvorak and Schubert - concert review

- Stories in music in Oxford: visual inspirations from the Mendelssohn siblings, William Blake in song & image, vivid story-telling from Wolf & Mörike - concert review

- Golden Jubilee: Pianist Piers Lane joins Norwich-based orchestra, the Academy of St Thomas for celebrations - concert review

- Fierce & intense: Peter Konwitschny's production of La traviata returns to ENO with a mesmerising account of the title role from Nicole Chevalier - opera review

- Long may they continue! Kronos Quartet's celebratory 50th anniversary concert at the Barbican - concert review

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment