|

| Eímear Noone (Photo: Andy Paradise) |

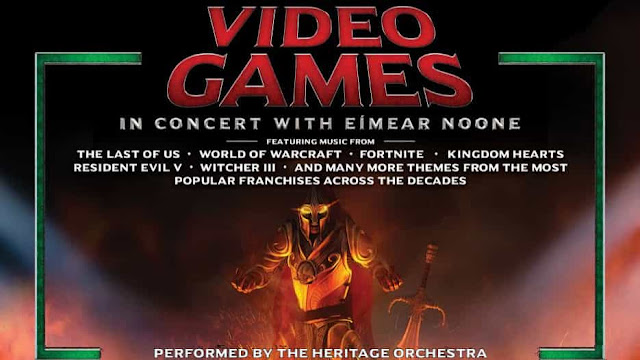

Dublin and LA-based composer Eímear Noone is known for her scores for video games, films and TV. She received a Hollywood Music in Media Award for Best Video Game Score, and recent work also includes the score for Maxine the drama series on Channel 5 and the new production by Stephen Fry based on Oscar Wilde’s short story The Canterville Ghost. Her music from World of Warcraft featured in the 2023 BBC Prom celebrating soundtracks from the worlds of film, TV and gaming. But she can also be found regularly on the concert platform and in May 2024, Eimear will be conducting The Heritage Orchestra in Video Games in Concert, an orchestral tour visiting Brighton, Liverpool, Wolverhampton, Manchester and Bournemouth.

The idea of presenting music from video games in concert, without the visuals from the games, is a deliberate one on Eímear's part, she loves the orchestra and wants the audience to appreciate it. The orchestra is theatre enough; she has done plenty of synch screen concerts, but found that the audience members simply stare at the screen and as far as Eímear is concerned, they can do that at home. So she decided to do without and found that in the orchestra-only format, the audience comes with her and the results are fun and get a great reception.

It helps that she is a classically trained musician, and sees the concerts as a way of sharing her love of the orchestra with a massive audience. But audiences also appreciate the human element in the performance; it is not out of a box and people experience something that feels real. And, as in her experience of classical performances, every performance is different.

Music has multiple uses in games, some linked directly to specifics of the way games work and others more general. Music has a rather cinematic use in setting up the game, and the lore, and it can also be used to fully immerse the player in the imaginary world by creating a sonic landscape, helping the player to leave the everyday. This sense of full immersion, getting into the imaginations of the players by using music, is an important one in modern games. She comments that the human spirit loves to play, and this is something she guards when writing music for a game.

There are also interactive elements that are more game-specific, these need to be a series of elements that work separately or in combinations, rather like a puzzle. The exact usages depend on what things the player has triggered, and some elements might need to be able to loop. A more recent innovation is the idea of using AI to add an element of chance to the mix, based on what the characters are doing at the time. Eímear views this usage creatively, likening it to the development of indeterminate music, using aleatoricism or chance.

There is one final usage for music, dialectic music or situational music. Here the music is happening within the game, whether it be lift music, background music in a hotel foyer, a cabaret or similar. This requires the composer to write in a style based on the event; in a film, this music might simply be licensed but in video games, the composer tends to write it, which is a nice challenge. And Eímear comments, rather proudly, that she recently wrote a French chanson! All this is fun because it means you have to stretch your creativity to do what the developers want.

Eímear studied at Trinity College, Dublin and whilst in college she was not aware of video game music. As a teenager, she had been drawn to atonal and serial music but attended a Summer school given by Finnish composer Kalevi Aho (who studied with Einojuhani Rautavaara and Boris Blacher). Aho warned against boxing yourself in stylistically, with no use of traditional harmonies or melody. Eímear thought about going further and simply blowing the box to pieces.

.jpg) |

| Video Games in Concert at the Royal Albert Hall in 2023, Video Games in Concert - Eímear Noone & the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra (Photo: Andy Paradise) |

Whilst at Trinity College, UCLA opened an outpost which enabled Eímear to do film music modules. Her first big credit came about by accident; she was rehearsing with the chapel choir and afterwards, one of the senior students asked for singers who could sight-read to record some choral music. She had no idea what the recording was for, and only later learned that it was for part of the score for the game Metal Gear Solid.

The UCLA extension programme also brought a Hollywood orchestrator to teach some modules and based on her work for these modules the orchestrator asked her to assist him on what would be the first World of Warcraft. Here the music was purely choral and orchestral, using just an orchestra, what she calls 'a machine that we love'. The score would be heard by 100,000 players during the game's 10th anniversary. At the time of originally working on it, she had no idea it was going to be a hit.

She describes gaming as running alongside the regular work with separate rules, and the gaming audience is fantastic.

When I ask whether she encountered any issues being a female composer in the gaming world, she says that she sneaked in when they weren't looking. Growing up in her family, in a small village, she was not aware of her gender, nor did she consider that what she wanted to do was noteworthy. Whilst issues relating to gender remain a professional concern, she does not feel particularly gendered on a daily basis, she is aware but it does not influence her internally.

There is some overlap between film music and game music, and some differences too. In a film, you are governed by the vision of the director, whilst in a game the lore sets the style of the music. Both of these situations set the context, the harmonic language and instrumentation. She also enjoys things that she has not done before, and both film and video game music use similar or the same technical tools. You can also produce music similarly, so that in an action film you might record musical stems, much as you do for the interactive sections of a video game, so that there is more flexibility when it comes to the dubbing stage.

But the scoring of the game also gives more creative freedom, within the game environment there is nothing to constrain you. The scene-setting music from games is what is often chosen for the concert performances, creating suites of themes. The game music needs to be as creative as possible, and the challenges can stimulate different thought processes. The situation and purpose of the music might be different between film and game, but to the audience, they can often seem the same.

Her background and training refer back to writing purely concert music, though she admits that she has not done it for a while. But she is excited that there is a concert project coming up, though it is a challenge to find her own voice which can change at different periods of your life. With concert music she relishes that there is no-one else leading the creativity, it is all down to her. That said, she loves the collaborative aspect of film and game music.

When composing, if it is an orchestral score then she composes directly into the notation programme because she needs to see the notes, she needs every detail there, to see and feel the orchestra. She has spent so much time conducting orchestras that she sees and hears the orchestra. When mixing the soundtrack, she wants the orchestra to sound big, spatially the same as the conductor hears. This is the sound that she is trying to recreate.

|

| Eimear Noone (Photo: Frances Marshall) |

Video Games in Concert UK Tour with Eímear Noone will run throughout May, featuring scores from classics such as The Last of Us, Uncharted, and World of Warcraft as well as new arrangements from recent hit games including God of War: Ragnarök, Starfield, and more.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- As chilling and emotional as ever: Kate Lindsey returns as Offred in ENO's strong revival of Poul Ruders' The Handmaid's Tale - opera review

- Fiery & fully committed: Manchester Collective in Freya Waley-Cohen's Spell Book at the Barbican - concert review

- Being themselves: the young artists of the National Opera Studio in Simple Gifts, a programme of song from across the globe - concert review

- Identity, displacement and homesickness: Raymond Yiu's new violin concerto inspired by the experiences of Chinese violinist and composer, Ma Sicong - feature

- Back with vengeance: Nina Stemme in Richard Strauss' Elektra at Covent Garden - opera review

- What happens when a conductor best known for his operatic work, conducts Mendelssohn's Elijah: Sir Antonio Pappano & the London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican with Gerald Finley - concert review

- Awash with musical history: Thea Musgrave's Mary, Queen of Scots at Oper Leipzig, Shostakovich celebrated by Gewandhausorchester, Leipzig Music Trail, Mendelssohn Haus, Bach Archiv & more - feature

- Home

- From Classical to Romantic: I chat to Michael Sanderling about the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra - interview

- A winter week focusing on the piano yet hosted by an orchestra: intendant Numa Bischof Ullmann introduces Lucerne's Le Piano Symphonique & looks forward to the 2025 festival - interview

- Homage to Liszt: pianist Benjamin Grosvenor on astonishing form in Liszt and Brett Dean - concert review

- Liszt Cycle 2: From large-scale Liszt and Wagner to intimate Schumann and Schubert - concert review

- Made in Switzerland: tenor Daniel Behle and pianist Oliver Schnyder combine musicality and intelligence - concert review

- Liszt Cycle 1: From poetic Liszt and Grieg concertos to a little bit of magic from Martha Argerich and friends - concert review

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment