|

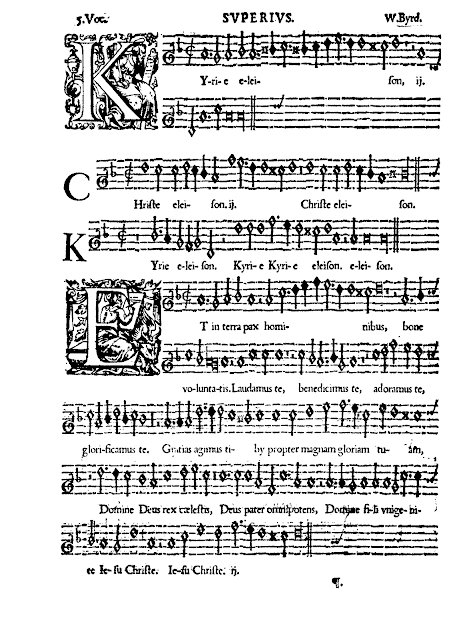

| William Byrd: Mass for five voices Kyrie - Superius part |

Reviewed 21 December 2022 (★★★½)

Almost into its 50th-anniversary celebrations, the ensemble gave us a gloriously mixed bag of polyphony, from early to late Tudor, plus Italy and beyond, a rich and vibrant diet

A capacity house at St John's Smith Square's Christmas Festival on Wednesday 21 December 2022 heard Peter Phillips and the Tallis Scholars giving their final concert in what is their 49th anniversary year; next year the ensemble celebrates being 50.

It wasn't particularly a Christmas programme, though a Marian theme ran through a number of items. There was William Byrd's Mass for five voices alongside Nicolas Gombert's Magnificat III and Regina Coeli, Robert Fayrfax's O Maria deo gratia, Taverner's O splendor gloriae and Gesualdo's Ave dulcissima Maria. There were ten singers, two to a part in the Byrd, and the other music moved smoothly between different numbers of voices, the ten singers re-configuring to suit so that the Gombert Magnificat moved from three voices to eight, whilst his Regina Coeli was a whopping ten voices.

Byrd's mass dates from the 1590s, written for Catholic recusants during the later period of Queen Elizabeth I's reign when to be a Catholic was a major political statement. The form of Byrd's masses seems to have been somewhat influenced by the music of English composers of the earlier generations, and the Mass for Five Voices has suggestions of the structure of Taverner's music. But the masses also reflect the needs of the recusant community. Relatively short, and flexible forces with a style and structure suitable for masses said by Continental trained priests who did not use the Sarum rite that had been so prevalent in England.

The masses, for all their masterly writing, are not without challenges. Byrd's part writing does not always seem to take account of the fallibility of voices, and it has been argued that the Mass for four voices works best when transposed down and sung not SATB but ATBaB. For this performance of the Mass for five voices, the Tallis Scholars used the standard SATTB edition familiar to most choristers.

We began with the Kyrie and Gloria from the mass, the Credo came at the end of Part One and the remaining movements began Part Two. This was a poised and elegantly shaped performance, each voice moulding the phrases. There was also a relaxed quality, though speeds were not slow, and throughout the movements of the mass, we could hear the words clearly. In the Gloria, there was a nice contrast between the sections for smaller groups and the tutti moments. In these latter, the ensemble made a vibrant rather direct sound which was very much tenor-led. This was unsurprising, there are two tenor parts and both sit quite high, but there were times when I wished the tenors would take more of a back seat in the overall mix. This continued in the Credo, which Phillips kept moving yet ensured clarity of words, and there was a lovely affirmative quality to the closing pages. The Sanctus was beautifully realised, with a vigorous Hosanna, and a Benedictus that slowly unfolded, ending with the finely moulded phrases of the Agnus Dei. But for all the performance's beauties and sensibilities, my notes kept coming back to the tenors and their over-prominence in the mix.

Robert Fayrfax's O Maria deo grata is a large-scale antiphon in the style familiar from the Eton Choir Book, though this antiphon has a somewhat curious history. It was originally for St Alban, O Albande deo grate but later adapted presumably to give it wider appeal. The treble and tenor parts do not survive and are modern reconstructions. Phillips directed as if there was all the time in the world, allowing the sombre polyphony to unfold. Despite the enlivening of highly rhythmic writing, the overall effect was sober and the long-breathed writing and remarkable long-distance architecture with syllables seeming to last pages represented a major difference to the Byrd.

By contrast, Carlo Gesualdo's Ave dulcissima Maria sounded positively madrigalian and was certainly far less anguished than much of this composer's work. It was simply lovely, with mobile textures and malleable harmonies.

Nicolas Gombert's Magnificat III is the third of his cycle of eight Magnificats. The story goes that after Gombert was sentenced to hard labour on the galleys for sexual misconduct with a boy in his care, these Magnificats are the works that won him a reprieve. Almost certainly only a story, the music is however supremely wonderful. Gombert alternates plainchant with polyphony and each new polyphonic verse adds a voice, moving in a stately fashion from three to five voices, creating wonderful, rich and vigorous polyphonic textures. The tone from all the men (tenors and basses) was very vibrant indeed and was sometimes in striking contrast to the more modulated tones of the women (sopranos and altos). Gombert's Regina Coeli moved us to ten voices (the composer also wrote a 12-voice setting of the text), here in a piece of gloriously imaginative writing, the busy polyphony was sung strongly by all voices.

John Taverner's O splendor gloriae is a glorious, large-scale piece preserved in the part books from Taverner's time at Cardinal College (now Christ Church, Oxford). The piece is attributed to Taverner and Christopher Tye, which is relatively unusual for the time and may indicate that they each worked on different sections. Again, we felt that there was all the time in the world, with strong, big-boned polyphony sung with great robustness. And, sorry for seeming to harp on, but I came away from this performance again with a feeling of lack of balance in the vocal lines with the men, tenors particularly, overdominant.

There was an encore, a delightful double-choir version of Joseph lieber, Joseph mein by Hieronymous Praetorius.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A daring and refreshing project: 12 composers, 12 different approaches - Carols after a Plague from The Crossing - record review

- In fine fettle: conductor Maxim Emelyanychev brings an interesting element of period style to the latest Magic Flute revival at Covent Garden - opera review

- Natalya Romaniw, Freddie De Tommaso, & Erwin Schrott in Puccini's Tosca at Covent Garden - opera review

- A lovely way to begin the Christmas season: Handel's Messiah from Laurence Cummings & Academy of Ancient Music at Barbican Centre - concert review

- Making ancient music sound modern: Franck-Emmanuel Comte on Le Concert de l'Hostel de Dieu's mixing old & new music, collaborating with beatboxers, hip-hop and more - interview

- 20 Christmas pieces by 19 women composers from the 20th and 21st centuries: Somerville College Choir's The Dawn of Grace - record review

- To enter White's world is to enter a parallel universe: Alastair White's opera Rune recorded live on Metier - record review

- Manic energy and musical vision: Alex Paxton's ilolli-pop on nonclassical - record review

- How Cold the Wind doth Blow: songs by RVW, friends and pupils at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- A tricky relationship: the friendship of Benjamin Britten and W H Auden examined in London Song Festival's final event of the season - concert review

- Persephone: young film composer Veronika Hanl's lockdown project began as the stripped-back telling of a classic tale from Greek mythology - interview

- Music that barely survived, brought back to life: Ensemble Pro Victoria's Tudor Music Afterlives - record review

- Home

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment