|

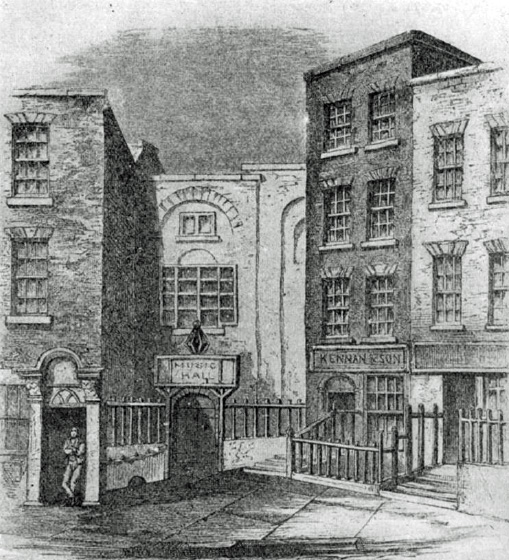

| The Great Music Hall in Fishamble Street, Dublin, where Messiah was first performed |

Handel: Messiah (1742 version); Hilary Cronin, Helen Charlston, Anthony Gregory, Edward Grint, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Peter Whelan; Wigmore Hall

A wonderfully vital and compelling account of Handel's original version of Messiah where the performers' sheer sense of joy came over in every note.

Handel's Messiah has become so ubiquitous at Christmas that we can often forget that the work encompasses not just Christ's birth, but his passion and resurrection, and that Handel's oratorios were typically performed during Lent or Eastertide. The premiere of Messiah took place some three weeks after Easter in Dublin in 1742, at the Great Music Hall, Fishamble Street, Dublin. Only the entrance arch of this building survives, so we have no idea of size, but we have to assume that it was rather closer to the Wigmore Hall than the Royal Festival Hall.

So, the performance of Handel's Messiah at Wigmore Hall on Sunday 2 April 2023 (Palm Sunday) by the Irish Baroque Orchestra, directed from the harpsichord by Peter Whelan, is not so strange after all. The performance used Handel's original 1742 version of Messiah, with a small instrumental ensemble (nine strings, organ, harpsichord, no woodwind, trumpets & timpani) and a vocal ensemble of 12 including the soloists Hilary Cronin, Helen Charlston, Anthony Gregory and Edward Grint.

In an age when we seem to love investigating the original versions of things, it seems strange that the original version of Messiah remains so very rarely performed. It gives us Handel's first thoughts, written, unusually for him, before he knew who his soloists were. The work is completely recognisable, yet there are differences, moments in recitative which would become arias, versions of arias which would be replaced and some missing items like 'Their sound is gone out' (which was added in 1743). I remain rather fond of the original, triple-time version of 'Rejoice greatly' and the alto duet version of 'How beautiful are the feet'.

Handel used 16 boys and 16 men for his first performance of Messiah, plus two female soloists (the male solos being sung, probably, by men from the choir); at Wigmore Hall we had 12 singers in total on an extremely full platform. Anyone worrying that the work would lack impact, however, was profoundly mistaken. This was a performance that took full account of the forces and the space, and the great moments had a terrific impact, not through sheer weight or mass but because of the remarkable control of the singers and the acuity of Whelan's direction.

Choruses were full of crisp articulation and clarity, words were always prominent and singers were highly responsive. With 12 professional singers and a balancing number of instrumentalists, Whelan was about to bring out a remarkable amount of detail in the music, and weight was achieved by emphasis rather than sheer numbers. And there was excitement too, he and his performers made moments like the Hallelujah Chorus into pieces of sustained excitement. Speeds were often swift, and there were plenty of times when I marvelled at the singers' control, not just in the solos but in the choruses too. However, unlike some period instrument performances of the work, I never got the feeling here that speed was for the sake of it, there was no sense of 'look aren't we clever', Whelan's speeds always felt organic. What was also noticeable was how much enjoyment the singers seemed to be having, and this communicated itself throughout the performance.

The soloists were able to take far more risks, singing rather quieter than is often the case in a larger hall, bringing a sense of intimacy, and confiding in the audience. Hilary Cronin brought a richly warm sound to the soprano solos. Her Angel in part one was poised yet feminine and demure, with a real sense of excitement at the message culminating in a joyous account of 'Rejoice greatly'. In 'I know that my Redeemer liveth' she combined a confident sense of the text's meaning with a rather nice swing to the rhythm.

Helen Charlston sang the alto solos with a lovely straight tone and nice directness. 'O thou that tellest' combined seriousness of purpose with a nice rhythmic bounce, whilst 'He shall feed his flock' had a telling sense of understatement. 'He was despised' had a sense of movement to it, with shape to the accompaniment and Charlston's remarkably intimate delivery. Throughout her performance, you sensed the commitment to the words, which came over right through her final solo 'If God be for us.

Tenor Anthony Gregory sang with a fine sense of line and burnished tone, with a wonderful strength to his words. 'Ev'ry valley' was serious of purpose, with fine passagework indeed. In part two, he made notable contributions, bringing out sense and meaning in the various recitatives, culminating in a remarkably trenchant 'He that dwelleth in Heav'n'.

Bass-baritone Edward Grint's opening recitative was finely trenchant, whilst 'For behold' had a lovely veiled intimacy. In part two, 'Though art gone up on high' flowed beautifully. 'The trumpet shall sound', preceded by rather intimate account of the recitative, was strong, yet flowing and full of character with a real sense of triumph at the end.

Altos Nathan Mercieca and Mark Chambers sang 'How beautiful are the feet' with gentle tone and swaying rhythm, whilst Chambers and Anthony Gregory made 'O death, where is thy sting' nicely light. Bass Frederick Long sang 'Why to the nations' with concentrated power and superb passagework, despite the fast speed.

This was one of those performances where the words mattered. You could hear every word, no matter how quietly the soloists sang, nor how fast the chorus passagework was. Words were at the forefront, just as they should be in an oratorio.

Throughout the performance, there was that sense of enjoyment from the performers and an invigorating vitality. Whelan was not shy of bringing out the underlying dance structures of the music, even in the most serious of pieces. Overall, this was a remarkable ensemble performance, turning Messiah into a compelling piece of story-telling where small scale did not mean a lack of commitment, drama or power.

Singers: Hilary Cronin, Alison Ponsford-Hill, Julie Cooper - soprano, Helen Charlston, Mark Chambers, Nathan Mercieca - alto, Anthony Gregory, Stuart Kinsella, Tom Kelly - tenor, Edward Grint, Frederick Long, Dan D’Souza - bass

Instrumental ensemble: Matthew Truscott, Alice Earll, Marja Gaynor, Henry Tong, Anita Vedres - violin, Oliver Wilson viola, Sarah McMahon, Aoife Nic Athlaoich - cello, Malachy Robinson - double bass, Malcolm Proud - organ, Darren Cornish Moore, Paul Bosworth - trumpet, Robert Kendall - timpani, Peter Whelan - director, harpsichord

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Korngold looks back: the lushness & extravagance of fin-de-siecle Vienna evoked in The Dead City at English National Opera - opera review

- Focus on Manchester:

- A joy in telling stories in music: the Manchester Camerata, the Monastery & music - feature

- Successfully integrated into the same eco-system, The Stoller Hall and Chetham's School of Music - feature

- Let other pens dwell on misery and grief - a joyous ensemble performance of Jonathan Dove's Mansfield Park from RNCM Opera - opera review

- The latest in Manchester Camerata's Mozart, Made in Manchester series featured a lovely creative dialogue between Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Gábor Takács-Nagy and the players - concert review

- Henning Kraggerud & RNCM Chamber Orchestra in RNCM's Original Voices Festival - concert review

- Every phrase has a story behind it: Gábor Takács-Nagy on conducting Mozart and more - interview

- Handel in Rome: Nardus Williams and the Dunedin Consort at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- After Byrd: HEXAD Collective launches its concert series exploring hidden music for voices - concert review

- The go-to place for information about opera performances across the globe: we chat to Operabase's new CEO, Ulrike Köstinger - interview

- A lockdown success story: St Mary's Perivale and its amazing programme of 120 recitals per year, viewed live and online - interview

- Late romanticism and youthful vitality: Cello Concertos by Enrique Casals & Édouard Lalo from Jan Vogler & Moritzburg Festival Orchestra - record review

- Home

.jpg)

%20Craig%20Fuller.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment