|

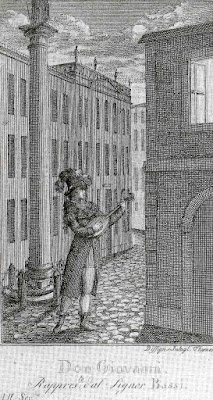

| Luigi Bassi in the title role of Don Giovanni in 1787. |

Audiences of the time would not have made anything of this type of doubling, operas with large casts frequently had singers playing multiple roles. The fact that the same person appeared as, say, Masetto and the Commendatore did not say anything special about either character.

But modern audiences can experience a different kind of creative doubling, where having the same singer playing multiple roles links the roles psychologically, making them seem as if they are aspects of the same person, or in some cases creating a single composite character from multiple disparate roles.

|

| Britten: Death in Venice - Gerald Finley and the players - Royal Opera ((c) ROH 2019 photographed by Catherine Ashmore) |

Les Contes d'Hoffman, with libretto by Jules Barbier, is based on short stories by ETA Hoffman. By making the same singers play the four heroines, and the four villains, Offenbach and Barbier provided an interesting psychological linkage between the stories, making each an aspect of the poet hero's psychological disintegration. The use of the word psychological may be anachronistic (whilst the word has been around since the 17th century it is only from the end of the 19th century it came to be seen as the science of the mind), but clearly some such similar thought was going through Barbier's head. And by combining these roles, and writing different style music for each, Offenbach created single multifaceted roles which become a supreme challenge for the singers.

And conversely, if the linkages are unpicked then the psychological aspects of the opera are reduced. The sheer challenge of performing the four soprano roles or the four baritone roles means that some companies choose to cast with different singers, with the result that one underlying aspect to the drama is reduced and the opera can appear to be little more than a picaresque narrative.

Such a psychological interpretation can be applied even if the composer did not envisage it. In his 1987 production of Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel for English National Opera, David Pountney set the piece in the 1950s and made the witch and her house simply glamorous, prosperous versions of the mother and the children's house. Mother is downtrodden, struggling financially, testy of temper but ultimately deeply caring, whilst the Witch is glamorous, prosperous, and apparently friendly but ultimately evil. This combined role also provides an interesting challenge for the performer, Humperdinck wrote the Mother as a soprano and the Witch as a mezzo-soprano (this latter role is sometimes taken by tenors and I have seen it sung by a counter-tenor), but combining the two requires a soprano with a wide range, thus creating an interesting vocal challenge for the singer in addition to the multi-faceted dramatic role.

|

| Gwynneth Jones as Venus in Wagner's Tannhauser at the Bayreuth Festival |

Perhaps the most intriguing Richard Strauss doubling came about by accident, when a singer pulled out at the very last minute for a concert performance of Strauss' Die Frau ohne Schatten, and Gwyneth Jones agreed to sing both the Empress and the Dyer's Wife. The two DO share a limited amount of stage time so this would not make a viable production, to say nothing of the sheer physical stamina needed to sing both roles. But it provides an interestingly different way into the story.

Of course, this does not always work. Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana and Leoncavallo's Pagliacci are now almost universally performed as a double bill, but they were not written so. But from quite early on, these two Verismo classics have been linked, in fact the two operas virtually define Italian Verismo opera. This has led producers to try to make sense of the double bill by having the same singers in each (quite a challenge for the tenor), but dramatically this concept usually struggles to add coherence to what are in fact two rather disparate stories. At Opera Holland Park in 2013 Stephen Barlow played the two in the same village, but with a time-lapse and the play-within-a-play in Pagliacci became a farcical version of Cavalleria Rusticana [see my review], whereas other directors (Ian Judge in the old English National Opera production, Damiano Michieletto at Covent Garden [see my review]) create a simpler linkage by setting the two in the same village.

When Barrie Kosky directed Handel's Saul at Glyndebourne in 2015 [see my review], his vividly conceived, yet abstract production was set in a loosely Georgian setting. Whilst the mis-en-scene kept the basis of the original plot, Kosky combined four of the smaller tenor roles (Abner, the High Priest, the Amalekite and Doeg) into a single role which became a sort of Shakespearian fool, thus giving the singer (at the premiere Benjamin Hulett) a far greater dramatic challenge and making something satisfyingly complex out of a group relatively ordinary roles. Of course, this required adjustments to the dramaturgy which not everyone would enjoy, but after all Saul was not originally written to be staged. Here we see not the creation of a psychological view, but rather the assemblage of a single composite character.

|

| Puccini: Manon Lescaut Act 3 - Elizabeth Llewellyn - Opera Holland Park 2019 (Photo Robert Workman) |

When used intelligently, creative doubling can provide new and different insights into existing works, as well as giving singer some interesting challenges. With myth and fairy tale based stories, such doubling of roles can dig into some of the more psychological aspects of the piece in ways which are fascinatingly creative.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Pianist Iyad Sughayer in Khachaturian, Mozart and Liszt for the City Music Foundation (★★★★) - concert review

- Spareness, clarity, quirkiness: William Howard plays Howard Skempton (★★★★) - cd review

- The cello sonata from early Beethoven to Shostakovich: Anglo-French duo Lydia Shelley & Nicolas Stavy at Conway Hall - concert review

- The shipwrecked world, and nature extinct: Musica Antica Rotherhithe gives the UK premiere of Michelangelo Falvetti's Il Diluvio Universale in aid of Operation Noah - concert review

- The two are very different disciplines: best known as a film & TV composer, I chat to Stuart Hancock about 'Raptures' his new disc of concert music - interview

- The art of the lute: Thomas Dunford and the Academy of

Ancient Music put the Baroque lute in the spotlight from concertos to

trio sonatas and a solo suite (★★★★) - concert review

- Wild Waves & Woods from Sweden: the Västerås Sinfonietta at Kings Place (★★★★) - concert review

- Ductus est Jesus: music from the Portuguese Golden Age from Gramophone Award-winning Portuguese ensemble Cupertinos (★★★★½) - concert review

- Welcome rarity: Verdi's Luisa Miller receives a strong musical performance in Barbora Horáková's new production at ENO (★★★★½) - opera review

- Extinction, Nature overwhelmed and toxic masculinity: music by Aaron Holloway-Nahum, Laurence Osborn, Liza Lim from the Riot Ensemble at Kings Place (★★★½) - concert review

- Teamwork, resilience, self-discipline: teaching life-skills through music, I chat to Truda White of MiSST (Music in Secondary Schools Trust) - interview

- Vividly engaged: Schubert's Death and the Maiden from the conductorless string orchestra, 12 Ensemble (★★★★) - CD review

- Home

The Frau Ohne Schatten where Gwynneth sang both the wife and empress was NOT a concert! It was a fully staged opera. The Empress was performed by an actress whilst Gwynneth sang (either with her back turned, or behind a scrim). They only sing together at the end, where another soprano sang from the pit.

ReplyDelete