|

| Cecilia Bartoli and John Osborn in Norma - Photo: Hans Jörg Michel |

Baritone Ricardo Panela looks at how the 1950s Bel Canto revival has influenced the way we listen to Bellini's Norma

The year of 2016 was a terrific year for Bellini lovers: the United Kingdom offered three productions of what is considered to be the pinnacle of Bel Canto opera: Norma. We had English National Opera’s production earlier in the year [see the review on this blog], followed by Cecilia Bartoli’s historically informed approach to the role for the Edinburgh International Festival, and ended with the Royal Opera House’s much anticipated new production starring Sonya Yoncheva [see the review on this blog]. I was lucky enough to attend two of these productions (ENO and ROH) and, inevitably, read the reviews of Cecilia Bartoli’s performance at the Edinburgh Festival.

This variety in offering of such an iconic opera leads to much comparison: this is, after all, a role which served as a vehicle for some of the most remarkable leading ladies of the XXth Century - Maria Callas, Montserrat Caballé and Joan Sutherland. From a singer’s perspective, I find the variety of ways in which one can tackle such an enormous role, absolutely fascinating: a woman who’s simultaneously a strong willed leader, a wronged lover and the torn mother of two children whose father she grows to loathe throughout the course of the plot. The emotional range required for this role is huge and that’s where much of its allure lies: the possibilities are endless.

However, what prompted me to write this article wasn’t so much to come up with a guide of ‘How To Sing Norma’, but to reflect about how this opera is perceived by the greater public and how biased we are (or aren’t) when someone tries to do something new with it. Cecilia Bartoli’s Norma is obviously very controversial and everyone has an opinion about whether or not it’s an adequate casting choice. However, focusing on that is missing the bigger picture of what is being attempted here.

For a very long time, we have listened to Bel Canto opera as it was rediscovered in the 1950’s, within a musical tradition which was essentially devoted to heavier repertoire, both German and Italian. Bel Canto music had been largely neglected for the previous fifty plus years and also singing technique had evolved in quite a different way, with emphasis being put on heft and volume rather than agility. These were after all the qualities necessary to tackle more declamatory roles against ever increasing orchestral forces.

When Callas began reviving these roles with Tulio Serafin, they did so in a musical context which was much different from the original aesthetic in which these roles were originally conceived. We can generally place early-romantic Italian repertoire between 1800 and 1850 and, in terms of development, as a direct development of the Classical tradition.

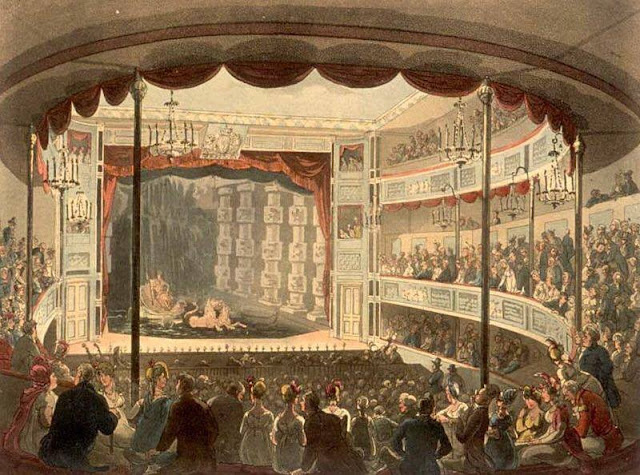

This influence of Classicism isn’t only relevant from a musical and stylistic point of view, but also when it comes to the layout of the theatre. In the 1950’s we already had the present layout which we’re so familiar with: orchestra in the pit and receded proscenium (a natural answer to managing the logistics of a bigger orchestra). This wasn’t, however, the case in the XIXth century where the theatre layout was still pretty much that of Baroque opera, with a proscenium that extended outside the stage box, and with the orchestra placed on the first rows of the stalls. The below image from the Sadler’s Wells in the 19th century illustrates the point perfectly.

|

| Sadler's Wells Theatre in the 19th century |

Bellini wrote the role of Norma for Giuditta Pasta who, by analysing some of the other roles written for her (Donizetti’s Anna Bolena, amongst others), would probably have a voice of similar range and colour to that Maria Callas: a dark-hued soprano, with terrific agility and an extended lower range. If we think about it, that sort of vocality perfectly suits the character which requires that huge emotional palette we discussed earlier. Nevertheless, Bellini did not write Adalgisa for a mezzo-soprano. This character is supposed to be one of the younger druid virgins and definitely younger than Norma, both in age and also in temperament. That sort of innocence just isn’t suggested by a mezzo-soprano sound, no matter how bright and how beautiful it is, and that is why Bellini’s original Adalgisa was Giulia Grisi (also Donizetti’s first Norina in Don Pasquale), for whom he wrote none other than Elvira in I Puritani, a role which we today rightly associate with a Lyric Coloratura soprano. This immediately changes the sonority of the duets and the musical dynamic between both roles and how they sing together.

As such, I believe that Cecilia Bartoli’s approach to the role by going back to the original manuscripts and trying to find the real Norma behind 60 years of modern tradition is perfectly valid. Whether or not the audience likes her in the role, the musicological and artistic value of her endeavour is undeniable and she deserves all the praise from trying to leave the Opera scene richer and more knowledgeable than she found it. After all, what she is doing with this music isn’t at all different of what Nikolaus Harnoncourt or Sir John Eliot Gardiner did with Mozart back in the 1980’s and 1990’s. If we compare what we now usually hear in the performance of a Mozart opera - period instruments and a generally more "sparkling" approach to the music -we realise how much the aesthetics of the "big music" were intrusive to the true nature of these works. This is also especially obvious in the studio recording of Bartoli’s Norma, where the amount of detail one can hear in Bellini’s orchestration and texture is truly astonishing. This is only possible when we have period instruments with their peculiar sound and mechanics executing this music.

Personally, I believe that this re-thinking these iconic works is part of a much needed re-imagining and re-discovery of this repertoire: we have incredible resources at our disposal today and all the tools we need to go back to the drawing board and defy conventions and expectations. The sources definitely exist: composers' letter reporting not only the rehearsal process but also the composition of the works and their relationships with the singers, exist in abundance. We have written records of the ornamentation and embellishments used by the great singers, which provide us a tremendous insight into how the variation of written music would work.

Bel Canto needs to find its true colours once more and I really believe it’s time for a Norma away from the norm.

Elsewhere on this blog:

- Christmas with the choir of St John's College: Choral at Cadogan - concert review

- Telling stories: Sir John Tomlinson in Schubert's Swansong at the Wigmore Hall - Concert review

- Magic and mystery: Society of Strange and Ancient Instruments at Spitalfields - concert review

- Rising to the challenge: W11 Opera perform Russell Hepplewhite and Helen Eastman's The Price - opera review

- Writing in her own style: I chat to harpist, clarsach player and composer Ailie Roberson - interview

- Circular music: Catches, rounds and ground bass from Pellingman's Saraband - CD review

- Dark story: Violinist Linus Roth in Shostakovich and Tchaikovsky - CD review

- Verbal acuity: Ben Johnson's Sonnets on Champs Hill Records - Cd review

- Stolen kisses: Songs of Alberto Ginastera - concert review

- Winning charm: Raphaela Papadakis and Sholto Kynoch at Omnibus Clapham - concert review

- Fifty mad minutes: Gerald Barry Alice's Adventures Under Ground - opera review

- Crossing boundaries: My interview with conductor Robert Ames - interview

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment