|

| Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies recording (Photo Richard Hughes) |

I first came across the name of the cellist Alfredo Piatti (1822-1901) in connection with the Cello Concerto which Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) wrote for Piatti. But Piatti was also a composer, and as such seems to be having something of a moment. Cellist Josephine Knight's recent disc for Dutton coupled Schumann's Cello Concerto with Alfredo Piatti's Cello Concerto No. 2 and Concertino for cello and orchestra, and in July, Meridian is issuing the second of cellist Adrian Bradbury and pianist Oliver Davies' two disc set of Piatti's operatic fantasies, 12 pieces in all, works which Bradbury and Davies have edited from Piatti's original manuscripts. I recently chatted with Adrian to learn more about Alfredo Piatti and his cello music.

|

| Alfredo Piatti, Lithograph by Eduard Kaiser, 1858 |

More seriously, he comments that his familiarity with the operatic fantasy as a genre goes back to his youth when his father, principal clarinet with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, would play such repertoire with Oliver Davies accompanying (Oliver is something of a family friend). So 30 years later things have come full circle, with Adrian playing the similar repertoire with the same pianist.

The immediate catalyst was a request from the London Cello Society to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Royal Academy of Music's (RAM) present building in Marylebone Road with an illustrated concert on Alfredo Piatti who was cello professor at the RAM (initially he was the only cello professor), and was there for 25 years. Piatti is a name familiar to cellists as all players love Piatti's Caprices (12 Caprices for solo cello, Op.25, written in 1865 and first published in 1875). Thanks to a colleague, Adrian already had the standard book on Piatti by Dr Annalisa Barzanò. Re-reading it, Adrian realised that for the RAM event they had to perform an operatic fantasy, a form for which Piatti was popular and famous. So they looked out what Piatti had played on his first visit to London, and it as an operatic fantasy based on the opera Beatrice di Tenda by Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) [Piatti's Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda is on Adrian and Oliver's first volume of Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies on Meridian]. First of all they had to acquire the music.

Alfredo Piatti was born of humble parentage in Bergamo (where Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848) was also born), and the young Piatti benefited from the encouragement of the composer Giovanni Simone Mayr (1763-1845), who was also Donizetti's teacher, and Piatti's manuscripts are now housed in the Donizetti Library in Bergamo, looked after by Dr Annalisa Barzanò and it was she who was able to provide a copy of Piatti's Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda. Adrian refers to Dr Barzanò as an amazing person, and her ability to quickly source and email copies of Piatti's manuscripts has been central to the project.

Piatti's Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda existed as something of a jigsaw, with different versions for piano and for orchestra. So, Oliver edited it, and he and Adrian performed the work at the Royal Academy of Music, and in Bergamo. There the project might have stopped, except that we come to the 'mid-life crisis' bit. Adrian and Oliver enjoyed the repertoire and started talking about performing, and recording, more of Piatti's fantasies. There were twelve in all, so that meant two discs.

A By-Fellowship at Churchill College, Cambridge enabled Adrian and Oliver to do more research on the operatic fantasies (Adrian had been an undergraduate at Churchill College). The college was very supportive of the project, Adrian and Oliver were not resident but gave concerts at the college, taught and recorded the music there.

At this point we start talking more generally about Piatti the composer, and the subject of Josephine Knight's new disc comes up and Adrian informs me that that Josephine Knight in fact is the current holder of the Piatti Chair at the Royal Academy of Music.

|

| Adrian Bradbury & Oliver Davies performing in Sala Piatti, Bergamo |

So what of Piatti's music? Having lived with the music for such a time, Adrian finds it beautiful. He also comments that when writing an operatic fantasy, the act of composition is a different one than when using only original material, and that Piatti has great respect for his original material. Adrian feels that you can see this quality in Piatti's transcription of Baroque sonatas. Piatti spent a lot of time looking at manuscripts in the British Museum, and his piano reductions of Baroque and early classical pieces, such as works by Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805), are honest and true to the original, they celebrate the music even though Piatti does add the odd florid flourish.

Piatti took his composing seriously and he had studied at the Milan Conservatoire, then whilst he was at the RAM he took composition lessons. And he had success with his work in England, particularly his songs. Adrian finds Piatti's music endearing, and comments that some of the operatic fantasies by Piatti's contemporaries are far less musically rewarding.

When playing an operatic fantasy, how aware do you need to be of the way singers would perform the music? Adrian feels that this sort of awareness is very necessary in this style of music, and he points to the fact that Piatti was very aware of singers himself and modelled his tone on that of singers. Eduard Hanslick (the 19th century critic) commented that Piatti did not use a sickly sweet vibrato all the time, but used a real cantabile to delight. Another critic said 'Piatti delights as much as he dazzled'. And from a young age, Piatti worked with all the great singers. Another writer said of him that he 'formed his cantabile on the singers from his own country'.

In the operatic fantasies that Piatti published, such as the one on Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, he uses a special ligature to refer to a bel canto singer's portato (a way of linking notes, related to portamento), and when Adrian and Oliver were rehearsing Piatti's Souvenir de la Sonnambula (based on Vincenzo Bellini's opera La Sonnambula), Oliver made Adrian go an listen to Bellini's opera live at Covent Garden (though familiar with the work, Adrian had never heard it live as an audience member). And Adrian found that he learned a lot by hearing singers performing the music and understood that that is what Piatti and his contemporaries would have done. The great Italian tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini was a good friend of Piatti's and in fact Piatti knew all of the so-called 'Puritani Quartet', the four leading singers of their day who had premiered Bellini's I Puritani in 1835, Giulia Grisi, Antonio Tamburini, Luigi Lablache and Rubini.

|

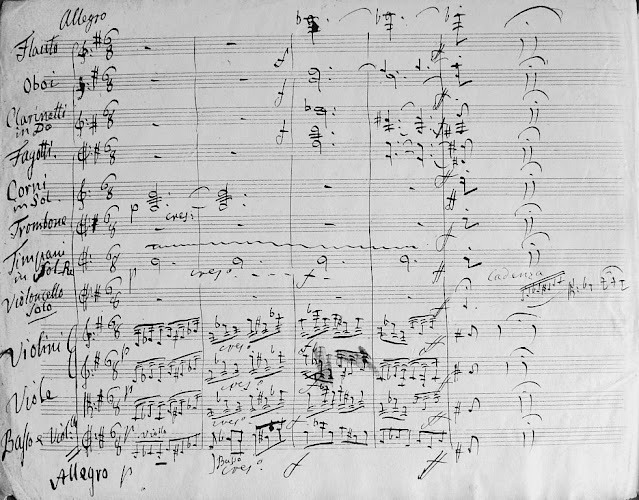

| Autograph manuscript of Alfredo Piatti's Parafrasi sulla Barcarola del Marino Faliero ©️Annalisa Barzanò |

And did Piatti write anything else? Pages and pages is Adrian's response. For a start he wrote a series of fantasies on national themes, Scottish, Russian and so on, and Adrian would love to have a look at these.

But as a cellist, Adrian's interest is not solely fixed on the 19th century. He enjoys studying repertoire from any era, and he performs a lot of contemporary repertoire with the London Sinfonietta and with the Composers Ensemble. He loves performing new pieces, loves the excitement of it even though he understands that much of what they perform will not last. He would be lost without it.

|

| Adrian Bradbury (Photo Richard Hughes) |

As for the future, well there is plenty more Piatti which could be recorded and Adrian also has another project bubbling under, related to early 20th century British music. But in the current situation, it is difficult to plan and he comments that the talk in the profession is a bit dismal, though Adrian feels on the whole optimistic, providing we have learned the right lessons. And he is looking forward to sharing the discoveries he has been making when normal life returns again.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Smoked beer, ETA Hoffmann and the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra: Tony explores the picturesque Upper Franconian town of Bamberg - feature article

- Icelandic experimentalism: Guðmundur Steinn Gunnarsson's Sinfonia explores non-traditional tunings and alternative notations - CD review

- Best

known as a conductor and orchestral composer, Sir Hamilton Harty's

expressively melodic songs are explored by Kathryn Rudge and Christopher

Glynn - CD review

- Intimate beauty: Iestyn Davies and Elizabeth Kenny in Elizabethan lute song, Purcell, Mozart and Schubert at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- Deliberately going against the grain:

Nicholas Collon, artistic director of Aurora Orchestra, on eclectic

programming, performing from memory and music of the spheres - interview

- A work usually starts with a conversation: I chat to percussionist Joby Burgess about new repertoire, collaborating with composers and playing during lockdown - interview

- Venice's Fragrance: this delightful disc from Nurial Rial and Artemandoline celebrates the 18th century's love affair with the mandolin - CD review

- A journey over the rainbow: Ailish Tynan & Iain Burnside take us from mature Grieg to Harold Arlen - concert review

- Contemporary re-invention: the String Orchestra of Brooklyn's debut disc features two works which re-invent fragments of classics - CD review

- A picture of a musical collaboration: In Seven Days from Thomas Adès and Kirill Gerstein - CD review

- Richard Wagner's heir, innovative festival director, opera composer, homosexual: the complex tale of Siegfried Wagner - feature article

- 'Home

%20as%20Leporello%20and%20Erik%20Tofte%20(back%20to%20camera%20in%20garnet%20shirt)%20as%20Giovanni%20-%20Don%20Giovanni.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment