|

| Apollo performed by Louis XIV, Ballet de la nuit 1653 |

In 1653, fourteen-year-old King Louis XIV of France took part in the Ballet Royal de la nuit, a ballet de cour which was highly elaborate and took 13 hours to perform. A twenty-one-year old Italian musician and dancer, Jean-Baptiste Lully (Giovanni Battista Lulli) danced with Louis in the ballet. The two got on and this relationship would have an important influence on opera in France. A strange mixture of politics and personal interest would ensure that, almost uniquely in Europe, the French rejected Italian opera and developed a style of opera very particular to France and the French language. And central to this process would by Lully.

But in 1653, opera hardly existed in France and the important genre was the ballet de cour, the name given to the 16th and 17th century ballets performed at the royal court, a distinctive French dance genre which mixed formalised and social dancing. Its influence was huge and French opera would combine elements of the ballet de cour, including the spectacular settings and large-scale portions for dancers.

And it would be Lully who codified the form of French opera, in his 13 tragédies lyriques or tragédies en musique. Of course, Italian courts in the 17th century had a love of spectacle too, but usually with less dance element to it. And opera in the two countries would be intriguingly linked, via a series of French royal marriages to members of the Medici family which ruled Florence.

Ballets de cour

Ballet de cour was a secular, not religious happening; it was a carefully crafted mixture of art, socialising, and politics, with its primary objective being to exalt the State (in the person of the ruler). Early French court ballet’s choreography was constructed as a series of patterns and geometric shapes that were intended to be viewed from overhead. Once the performance was through, the audience was encouraged to join the dancers on the floor to participate in a, "ball" which was designed to bring everyone in the hall into unanimity with the ideas expressed by the piece. As they developed through time, court ballets began to introduce comedy, went through a phase where they poked fun at manners and affectations of the time, and they moved into a phase where they became enamoured with pantomime.

|

| A 1592 engraving by Orazio Scarabelli depicting the mock sea battle, or naumachia, at the Palazzo Pitti |

Ballets de cour in France

When Catherine de’ Medici, the daughter of the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, married the French King Henri II in 1533, French and Italian culture enmeshed as Catherine brought from her native Italy her penchant for theatrical and ceremonial events, including elegant social dances. A more deliberate contribution to court ballet resulted from the Académie de Poésie et de Musique, founded in 1570 by the poet Jean-Antoine de Baif and the composer Thibault de Courville. The aim of the Académie was to revive the arts of the ancient world in order to harmonize dance, music, and language in a way that could result in a higher level of morality. It was from this marriage of traditional grand spectacle and conscious measured order that court ballets were born.

|

| Wedding ball of the Duc de Joyeuse and Marguerite of Lorraine, 1581 |

The first ballet de cour to fuse dance, poetry, music and design into a coherent dramatic statement was the Ballet Comique de la Royne Louise, performed in 1581 as part of the wedding celebration for the queen’s sister, Marguerite of Lorraine and the Duc de Joyeuse. The plot based on Ulysses’ encounter with Circe was symbolic of the country’s desire to heal old wounds and restore peace after the religious civil wars.

Reaching new heights in scale and diversity, the lavish five-hour production of the Ballet Comique de la Royne Louise included a three tiered fountain, palace, garden, townscape, and chariot-floats. As with the Ballet de Polonais, Beaujoyeulx choreographed using form, geometry, measure, and discipline as a foundation that would later develop into the codified ballet technique.

|

| Ballet Comique de la Reine of 1582 |

More French/Florentine royal marriages

In 1589 in Florence, Ferdinando I, Grand Duke of Tuscany married Christina of Lorraine, the grand-daughter of Catherine de Medici of France As part of the celebrations there was a performance of a play, La Pellegrina with musical entertainments between the acts, Intermedi. These Intermedi were worked on by some of the greatest writers, composers, and artists in Florence; the results weren't opera but those involved would go on to create the first operas. The Intermedi were a grand, complex theatrical musical sung entertainment, using mythological plots and utilising the latest advances in music and stagecraft. They were so popular that they were repeated, without the play and used at subsequent occasions as an event in their own right.

|

| The Florentine Intermedi of 1589 Design by Bernado Buontalenti for the Fourth Intermedio – a vision of Hell |

|

| Catherine de'Medici by Francois Clouet |

Catherine de Medici died in 1589, she would be the mother of three kings of France, Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III (the one who was King of Poland); she would see France convulsed in civil and religious wars, including the infamous St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. On the death of King Henry III in 1589, the kingdom would eventually be ruled by King Henry IV (a Protestant distant cousin whose grandmother was the sister of King Francis I of France). Henry IV converted from Protestant to Catholic to gain the crown after a bitter civil war; his reign would bring an element of stability to the country.

In 1600, the wedding, in Florence, of Marie de'Medici to King Henry IV

of France, included Jacopo Peri’s and Giulio Caccini’s opera Euridice

in the celebrations. The opera was a joint creation, and each composer

would subsequently create their own version. Operas written for such

grand occasions tended to be memorialised, as part of the wedding

display, which is why they survive in handsome printed copies.

On Henry IV’s death in 1610, he would be succeeded by his nine-year-old son, Louis XIII; Henry IV’s wife, Marie de Medici would act as regent from 1610 to 1617.

Louis XIII & Mazarin

King Louis XIII shared his mother, Marie de'Medici's love of the lute, developed in her childhood in Florence. One of his first toys was a lute and his personal doctor, Jean Héroard, reports him playing it for his mother in 1604, at the age of three. An important step towards the ballet de cour in its final form was taken during the reign of Louis XIII, with the creation of such rich and ravishing ballets de cour as La Délivrance de Renaud and the Ballet de la Merlaison.

In 1635, Louis XIII composed the music, wrote the libretto and designed the costumes for the Ballet de la Merlaison. In fact commentators dispute whether Louis XIII wrote the music apart from a couple of airs, and the majority may well be by Andre Danican Philidor, the elder. The king himself danced in two performances of the ballet the same year at Chantilly and at Royaumont.

King Louis XIII died in 1643, he was just 42. His chief minister since 1624 had been Cardinal Richelieu. Richelieu died in 1642 to be succeeded as chief minister by Cardinal Mazarin (born Giulio Mazzarino in the Abruzzo in Italy), who had worked for Richelieu. King Louis XIV was five years old at the time and his mother, Anne of Austria (in fact a Spanish princess) ruled in his place until he came of age. Mazarin helped Anne expand her power from the more limited power her husband had left her. Mazarin functioned essentially as the co-ruler of France alongside the queen during the regency of Anne, and, until his death in 1661 at Vincennes, Mazarin effectively directed French policy alongside the monarch.

The Fronde

Mazarin was not liked by ordinary Frenchmen. Paris was a city of about half a million people in the mid-seventeenth century, and in 1644 Mazarin tried to prevent the city growing further and to raise taxes by fining those who built houses outside the City Walls. This policy produced widespread resentment, and in 1648 popular discontent in the city erupted into open violence. The Fronde began in January 1648, when the Paris mob used children's slings (frondes) to hurl stones at the windows of Mazarin's associates. The civil wars lasted from 1648 to 1653, the second half being the Frond of the Nobles, the final attempt of the French nobility to do battle with the king, and they were humiliated.

The Fronde, as witnessed by the young King Louis XIV, made him come to dislike Paris and to distrust the higher aristocracy. In the long-term, the Fronde served to strengthen Royal authority, but weakened the economy; the Fronde facilitated the emergence of absolute monarchy.

Opera and Politics

|

| Set design by Torelli for Francesco Sacrati's La finta pazza, 1645, Paris |

Ercole Amante was a commission from Cardinal Mazarin to celebrate the wedding of Louis XIV and Maria Theresa of Spain. However, the grand preparations for the production resulted in delays and the opera was presented two years late. To cater to French taste eighteen ballet entrées and intermèdes with music by Isaac de Benserade and Jean-Baptiste Lully were inserted in Ercole Amante, mostly at the ends of acts. These were not merely diversions, but also served to further the plot. The theatre was built specifically to present the opera, and if the construction costs of the theatre are included, it was the most expensive of the French court's theatrical productions mounted up to that point.

This run of Italian opera would eventually come to a halt, partly through politics. Mazarin’s influence was disliked and the Fronde brought with it anti-Mazarin and hence anti-Italian feeling; Italian operas received a luke-warm reception. On the death of Mazarin, in March 1661 at the age of 23, Louis XIV assumed personal control of the reins of government and astonished his court by declaring that he would rule without a chief minister. One of his acts was to dispense with the Italian opera troupe (Cavalli was despatched back to Italy), and to support the creation of a French Academy of Poetry and Music.

The French also seem to have developed a dislike for the castrato voice, or perhaps the operation necessary.

|

| View of the early home of the Académie Royal de la Musique |

Académie Royal de la Musique

The poet Pierre Perrin began thinking and writing about the possibility of French opera in 1655, more than a decade before the official founding of the Paris Opera as an institution. The prevailing opinion of the time was the French language was fundamentally unmusical, but Perrin believed that this was completely incorrect. Seventeenth-century France offered Perrin essentially two types of organization for realizing his vision of French opera: a royal academy or a public theatre. In 1666 he proposed to the minister Colbert that "the king decree 'the establishment of an Academy of Poetry and Music' whose goal would be to synthesize the French language and French music into an entirely new lyric form." The result, established in 1669, would be the Académie Royal de la Musique, still in existence today as the Paris Opera.

Perrin converted the Bouteille tennis court, located on the Rue des Fossés de Nesles (now 42 Rue Mazarine), into a rectangular facility with provisions for stage machinery and scenery changes and a capacity of about 1200 spectators. His first opera Pomone with music by Robert Cambert opened on 3 March 1671 and ran for 146 performances. A second work, Les peines et les plaisirs de l'amour, with a libretto by Gabriel Gilbert and music by Cambert, was performed in 1672. Despite this early success, Cambert and two other associates did not hesitate to swindle Perrin, who was imprisoned for debt and forced to concede his privilege on 13 March 1672 to the surintendant of the king's music Jean-Baptiste Lully.

In 1673 Jean-Baptiste Lully took over and for the rest of his life he had the monopoly of large scale opera in France. During Lully's tenure, the only works performed were his own. The first productions were the pastorale Les fêtes de l'Amour et de Bacchus (November 1672) and his first tragédie lyrique called Cadmus et Hermione (27 April 1673)

|

| Theatre du Palais Royale: the home of the Academie Royale de la Musique |

Bigger premises

After the actor and playwright Molière's death in 1673, his acting troupe merged with the players at the Théâtre du Marais to form the Théâtre Guénégaud, and no longer needed the theatre built by Richelieu at his residence the Palais-Royal, near the Louvre. Lully greatly desired a better theatre and persuaded the king to let him use the one at the Palais-Royal free of charge

The first production in the new theatre was Alceste on 19 January 1674. The opera was bitterly attacked by those enraged at the restrictions that Lully, always jealous of his privilege, had caused to be placed on the French and Italian comedians. Louis XIV arranged for new works to be premiered at the court, usually at the Chateau Vieux of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. This had the further advantage of subsidizing the cost of rehearsals, as well as most of the machinery, sets, and costumes, which were donated to the Opéra for use in Paris.

|

| Jean-Baptiste Lully and Philippe Quinault's opera Alceste being performed in the marble courtyard at the Palace of Versailles, 1674 |

Lully

Lully was born on November 28, 1632, in Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, to a family of millers. His general education and his musical training during his youth in Florence remain uncertain, but his adult handwriting suggests that he manipulated a quill pen with ease. He used to say that a Franciscan friar gave him his first music lessons and taught him guitar. He also learned to play the violin. In 1646, dressed as Harlequin during Mardi Gras and amusing bystanders with his clowning and his violin, the boy attracted the attention of Roger de Lorraine, chevalier de Guise, son of Charles, Duke of Guise, who was returning to France and was looking for someone to converse in Italian with his niece, Mademoiselle de Montpensier (la Grande Mademoiselle).

|

| Portrait of Several Musicians and Artists by By François Puget 1688 Traditionally the two main figures have been identified as Lully & librettist Philippe Quinault. |

By February 1653, Lully had attracted the attention of young Louis XIV, dancing with him in the Ballet royal de la nuit. By March 16, 1653, Lully had been made royal composer for instrumental music. Between 1654 and 1685, his music would appear in nearly 30 ballets at court, some ballets du cour and others' ballets written to appear between the acts of stage works. The inclusion of dance movements, intermèdes, in plays led to the creation of the a mixed genre, the comedie-ballet.

In 1661, the playwright Moliere described comedie-ballets as "ornaments which have been mixed with the comedy" in his preface to Les Fâcheux Also, to avoid breaking the thread of the piece by these interludes, it was deemed advisable to weave the ballet in the best manner one could into the subject, and make but one thing of it and the play.

Intermèdes by Lully began to appear regularly in Molière's plays: for those performances there were six intermèdes, two at the beginning and two at the end, and one between each of the three acts. Lully's intermèdes reached their apogee in 1670–1671, with the elaborate incidental music he composed for Le Bourgeois gentilhomme and for Psyché. And most of Molière's plays were first performed for the royal court.

In 1672 Lully broke with Molière, who turned to Marc-Antoine Charpentier. Having acquired Pierre Perrin's opera privilege, Lully became the director of the Académie Royale de Musique.

After Queen Marie-Thérèse's death in 1683 and the king's secret marriage to Mme de Maintenon, devotion came to the fore at court. The king's enthusiasm for opera dissipated. There is nothing more intolerant than a reformed raked, and the king was now revolted by Lully's dissolute life and homosexual encounters. In 1686, to show his displeasure, Louis XIV made a point of not inviting Lully to perform Armide at Versailles

Lully died from gangrene, having struck his foot with his long conducting staff during a performance of his Te Deum to celebrate Louis XIV's recovery from surgery. Lully refused to have his leg amputated so he could still dance. This resulted in gangrene propagating through his body and ultimately infecting the greater part of his brain, causing his death,

|

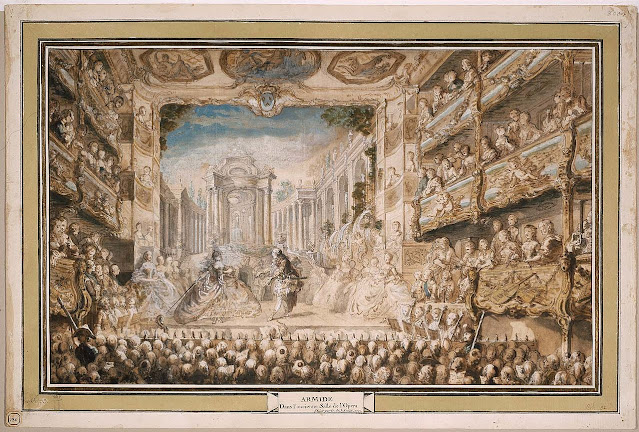

| Lully's Armide at the Palais-Royal Opera House in 1761 watercolour by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin |

Philippe Quinault

Quinault's first play was produced at the Hôtel de Bourgogne in 1653, when he was only eighteen; the piece succeeded, and Quinault followed it up, but he also read for the bar. In 1660, when he married a widow with money, he bought himself a place in the Cour des Comptes. Then he tried tragedies with more success. But in 1671 he contributed to the singular miscellany of Psyché, in which Pierre Corneille and Molière also had a hand, and which was set to the music of Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Here Quinault showed a remarkable faculty for lyrical drama, and from this time till just before his death he confined himself to composing libretti for Lully's work. This was not only very profitable (for he is said to have received four thousand livres for each, which was much more than was usually paid even for tragedy), but it established Quinault's reputation as the master of a new style, His libretti are among the very few which are readable without the music, and which are yet carefully adapted to it; they certainly do not contain very exalted poetry or very perfect drama.

Tragédie en musique

Operas in this genre are usually based on stories from Classical mythology or the Italian romantic epics of Tasso and Ariosto. The stories may not have a tragic ending – in fact, they generally don't – but the atmosphere must be noble and elevated. Lully and Quinault replaced the confusingly elaborate Baroque plots favoured by the Italians with a much clearer five-act structure. Earlier works in the genre were preceded by an allegorical prologue and, during the lifetime of Louis XIV, these generally celebrated the king's noble qualities and his prowess in war.

Each of the five acts usually follows a basic pattern, opening with an aria in which one of the main characters expresses their feelings, followed by dialogue in recitative interspersed with short arias (petits airs), in which the main business of the plot occurs. Each act traditionally ends with a divertissement, offering great opportunities for the chorus and the ballet troupe, which allowed the composer to satisfy the public's love of dance, huge choruses and gorgeous visual spectacle.

The recitative, too, was adapted and moulded to the unique rhythms of the French language and was often singled out for special praise by critics. The tragédie en musique was a form in which all the arts, not just music, played a crucial role. Quinault's verse combined with the set designs of Carlo Vigarani or Jean Bérain and the choreography of Pierre Beauchamp (ballet master at the Académie Royale de Musique and Compositeur des Ballets du Roi) and Hilaire d'Olivet, as well as the elaborate stage effects known as the machinery. As one of its detractors, the German-born French journalist Melchior Grimm, was forced to admit: "To judge of it, it is not enough to see it on paper and read the score; one must have seen the picture on the stage".

|

| Lully: Amadis - The Prison of Amadis in the original 1684 production |

Later developments

It was only after Lully's death that other opera composers emerged from his shadow. The most noteworthy was probably Marc-Antoine Charpentier,whose sole tragédie en musique, Médée, appeared in Paris in 1693 to a decidedly mixed reception. Lully's supporters were dismayed at Charpentier's inclusion of Italian elements in his opera, particularly the rich and dissonant harmony the composer had learned from his teacher Carissimi in Rome. Nevertheless, Médée has been acclaimed as "arguably the finest French opera of the 17th century". Other composers tried their hand at the genre, including Marin Marais and Andre Campra.

Jean-Philippe Rameau was the most important opera composer to appear in France after Lully. He was also a highly controversial figure and his operas were subject to attacks by both the defenders of the French, Lullian tradition and the champions of Italian music. Rameau was almost fifty when he composed his first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie, in 1733 (46 years after Lully’s death). Rameau died in 1764 by which time his operas were being attacked as old-fashioned.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Renowned as a pedagogue & the Royal Academy of Music's first cello professor, there is a lot more to Alfredo Piatti: I chat to cellist Adrian Bradbury about rediscovering Piatti's forgotten operatic fantasies - interview

- Smoked beer, ETA Hoffmann and the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra: Tony explores the picturesque Upper Franconian town of Bamberg - feature article

- Icelandic experimentalism: Guðmundur Steinn Gunnarsson's Sinfonia explores non-traditional tunings and alternative notations - CD review

- Best

known as a conductor and orchestral composer, Sir Hamilton Harty's

expressively melodic songs are explored by Kathryn Rudge and Christopher

Glynn - CD review

- Intimate beauty: Iestyn Davies and Elizabeth Kenny in Elizabethan lute song, Purcell, Mozart and Schubert at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- Deliberately going against the grain:

Nicholas Collon, artistic director of Aurora Orchestra, on eclectic

programming, performing from memory and music of the spheres - interview

- A work usually starts with a conversation: I chat to percussionist Joby Burgess about new repertoire, collaborating with composers and playing during lockdown - interview

- Venice's Fragrance: this delightful disc from Nurial Rial and Artemandoline celebrates the 18th century's love affair with the mandolin - CD review

- A journey over the rainbow: Ailish Tynan & Iain Burnside take us from mature Grieg to Harold Arlen - concert review

- Contemporary re-invention: the String Orchestra of Brooklyn's debut disc features two works which re-invent fragments of classics - CD review

- A picture of a musical collaboration: In Seven Days from Thomas Adès and Kirill Gerstein - CD review

- 'Home

No comments:

Post a Comment