|

| Bruce Ford as Rossini's Otello |

Bruce is working with the young singers of the festival academy on the vocal pedagogy that goes with the bel canto style. For bel canto, Bruce points out that you need to have the right style of technique to sing the music. He adds that whilst bel canto is known as beautiful singing, what is left out is that the style is more vocal calisthenics, showing off what the voice can do, so that singing in the true bel canto style can involve incredibly difficult melismas, high and low notes, to show off the virtuosity of the human voice. Bel canto is the ultimate presentation of athleticism and virtuosity in the human voice.

When I ask about his students' knowledge of bel canto, Bruce comments that the ones who are interested will educate themselves, and that is the way it is with anything. Such students are interested in their voices and are well rehearsed. For Bruce, bel canto is simply a specialism, a style used for music between 1810 and 1850 but after this opera under Verdi became something different.

|

| Bruce with his mentor Patric Schmid who tragically died in November of 2005 |

Bruce feels that there is a lot that modern students can learn from historical background, he points out that the 19th century singers sometimes received the music just before the first stage rehearsal of a piece. Such was their developed sense of the bel canto style that they would be able to sing this new music at such short notice, and he doesn't think that modern singers can compare in this skill.

He points out that it is very different with modern orchestral players, who at a recording session can pick up the music and busk through it, tidy it up, do a take, clean this up and then move on to the next passage. This was something that Bruce learned whilst recording roles with Opera Rara, that as a singer he needed to have everything ready to be able to do it this fast. This must have been the way singers were in the 19th century, so familiar with the style that they were just able to do it. He feels that young singers need to realise quite how the artists of the 19th century dedicated themselves to their craft, starting the training very early.

Bruce's career started with the roles that a young lyric tenor is obliged to sing in order to appear on the stage, becoming known for Mozart and for Rossini roles like Count Almaviva. It was in London that he was able to explore the rarer repertoire. For him, London has a rich tradition of doing the unusual and Opera Rara, and obliging philanthropists, made this happen. An enterprise like Opera Rara required a combination of vision and money, Patric Schmid (who founded Opera Rara with Don White) supplied the first whilst the philanthropist Peter Moores supplied the second. Moores was passionate about bel canto as an art form, he and Schmid would come together over breakfast and plan a recording. Both Moores and Schmid became friends of Bruce's and he still misses them.

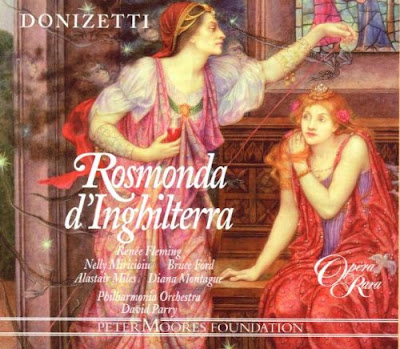

Many of the operas that Bruce recorded with Opera Rara were only ever done in the recording studio, and we would have loved the chance to perform them on stage and that some are simply phenomenal pieces. He mentions Donizetti's Rosmonda d'Inghilterra which is a somewhat problematic opera as it requires two divas and so is costly to mount. But for Bruce, it was one of the most exciting operas that he performed with Renee Fleming as the 'innocent' Rosamund and Nelly Miricioiu as the 'evil' queen. Bruce speaks fondly of Miricioiu, a singer with whom he worked quite a bit at Opera Rara, and refers to the fire and the phenomenal range of colours that she brought to a role.

Donizetti is a composer whose serious operas are rarely done on the stage, though Bruce has performed the comedies. He found Don Pasquale hugely enjoyable to perform, though the tenor role of Ernesto is tough to sing. As well as Rossini, Bruce recorded a lot of Donizetti for Opera Rara but also operas by his contemporaries Mercadante and Pacini. Bruce finds both wrote beautifully, and some of Pacini's writing was almost Verdian. At times Pacini used a thicker orchestration and takes the baritone really high and the tenors even higher. Bruce recorded Pacini's Carlo di Borgogna and recalls the way the top Cs came out of nowhere. Bruce loved performing this repertoire, being able to experiment and to examine the contemporaries to the more famous composers.

Another, slightly different role for which Bruce became known, particularly in London, was the title role in Mozart's Mitridate, Re di Ponto in Graham Vick's 1991 production at Covent Garden. Mozart was only 14 when he wrote the opera, and so had not yet made the change to the classical style and the opera is very much written in the late Baroque style which demanded great virtuosity. That said, Bruce finds the accompanied recitatives are works of real genius, though he comments that the ordinary recitatives are so awful that he feels they must have been the work of Mozart's father, Leopold.

For Bruce, Mitridate's last aria 'Vado incontro' is an interesting point. The original tenor wanted to sing 'his' aria (all singers of the period had arias which were their signatures which they carried from opera to opera) and instead of the original aria which Mozart had written, Mozart replaced it with his version of the other composer's aria. Here, Bruce demonstrates part of the melody to me (one of the delightful things of the interview was how Bruce would break into music to demonstrate a point).

This replacement of arias continued into the 19th century, and is a familiar occurrence in the musical history of Rossini's operas. It reflects the power of the singers in the era, something unlikely to happen in contemporary opera!

Bruce's career was always firmly in the Mozart and bel canto roles, he never ventured into more recent operas. His only Verdi role was Fenton in Falstaff and in fact he loved it, but he knew he would never be a Verdi singer, Verdi's orchestration had a thickness to it which requires a different voice. Bruce's abilities lay in the melismatic and high-flying music, rather than in the thicker middle voice. He was once asked to sing Alfredo in Verdi's La traviata, but this needs a ringing middle voice and Bruce feels that a lot of bel canto tenors have done it with varying degrees of success!

In Rossini operas, Bruce specialised in the roles written for Andrea Nozzari whose voice went up to the modern tenor's high G and down to A flat, but above G Nozzari would use the famous 'voix mixte' (very different in sound to the high Cs of a modern tenor like Luciano Pavarotti). This repertoire required some thickness to the middle voice but Bruce never pushed it and felt that a role like Alfredo would take things too far.

When Bruce performed the roles with the period instrument ensembles at historical pitch, this made an enormous difference to a high roles. When trying his first roles at historical pitch, Bruce thought 'gosh, this is easy to sing'. Modern, higher pitch, makes some roles trickier to sing and means that a singer needs to adjust techniques to suit. One technique that he learned from the great mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne (herself something of a specialist and pioneer in singing Rossini) was to re-centre the voice depending on the types of role he was singing (high or low), so that when he was singing the roles written for Andrea Nozzari the centre of his voice went down.

Bruce feels that it is good for a singer to know their limitations, he had a good top D but E flat would have been pushing it. He warns against the technical dangers in trying to stretch the voice too far, taking it up too high and down too far which can result in a split between top and bottom. And it is difficult for voice teachers to make sure that they are doing no damage. With later Italian opera, such as Verismo, a singer needs to add more stress to get the sound so that the voice has squillo, cutting edge, to rise through or above the heavier orchestrations. And creating this sort of sound makes it harder to get the high notes. Manrico's aria 'Di quella pira' in Verdi's Il trovatore famously does not include the high C in Verdi's original score, though it is added by later tenors, and Bruce feels that Verdi would never have expected it. When the tenor Gilbert Duprez sang the role of Arnold in Rossini's Guillaume Tell and used the chest high C, rather than the then traditional lighter 'voix mixte', Rossini hated it and said it sounded like a rooster being castrated!

I wondered whether Bruce had every cast an envious glance at tenors who had been able to move to these heavier roles. This is particularly true of the role of Otello, where Bruce became known for his performances at Rossini's Otello, but not Verdi's. He mentions his colleague Gregory Kunde who is one of the few tenors to have sung (very successfully) both Rossini's and Verdi's Otello. Something that Bruce finds utterly amazing. Bruce talks about the way the music that Verdi writes for Otello is descriptive in a way that Rossini's music is not, and here he vividly sings/talks me through Otello's final entrance in Verdi's opera, just before his murder of Desdemona. Bruce would have loved to have done Verdi's Otello, and finds this entrance phenomenal but he finds the ending of Rossini's opera in many ways better than Verdi's (heresy for a Verdi lover, he admits).

There are other roles which escaped him, ones which are more central to his repertoire. He would have loved to sing the title role in Rossini's final comedy, Comte Ory. He finds it a wonderful opera, and feels that a singer can have real fun in the role pointing to the recent production at the Metropolitan Opera in New York with Juan Diego Florez [see review in the New York Times]. Bruce recorded the trio from Comte Ory in English for his recital on Chandos Records, but never had the chance to explore the full role.

|

| Bruce as Tito in Mozart's Le Clemenza di Tito (Photo Bill Cooper) |

Bruce grew up listening to the great Swedish tenor Jussi Björling because Bruce's brother listening to him. Bruce loved what Björling did with his voice, and regards Björling as a bel canto tenor who was successful at singing heavier roles. When Bruce listens to Björling's recording of Canio in Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, he can hear how Björling is right at the edge of his ability. Whereas Puccini's La boheme is easly for a young voice, but in some roles a young or lighter voice can get into trouble. So many young singers get into trouble because they think, 'I can sing that'.

Bruce feels that in terms of the voice you should take what you have, use it to the best of your abilities, work hard and study your craft. He comments that a singer needs to pay their dues, and not cut corners going onto 'Britains Got Talent'.

One of the things that Bruce loves about the UK is that a large majority of the audiences at the opera know the repertoire and what the singers are singing. Bruce was based in the UK for 14 years and opera goers had true knowledge of what singers were doing, and appreciated it. In Italy, whilst some of the larger houses have audiences dominated by tourists, in many theatres the audience is similarly knowledgable. He comments that in somewhere like Parma the audience expects the best and, if they don't feel they are getting it will whistle you out the house. One of the things Bruce likes to look back on in his time singing in Italy is that during his career singing at Teatro alla Scala, in Milan (and he sang there a lot) he was never once whistled or booed, so at least the audience were content with what he did! Though he talks about a production of Rossini's Maometto II in which one of the other singers was booed and whistled each night. Singing in Italy was thus frightening and nerve wracking.

Bruce always thought of the Royal Opera House has his true artistic home, though he enjoyed his time working at Glyndebourne and thinks Graham Vick is a genius. Vick directed Bruce both in Rossini's Ermione at Glyndebourne and in Mozart's Mitridate at Covent Garden. This latter role was exhausting because of the costume, which weighed 40 lbs, and made worse by the logistics of getting round the back-stage areas of pre-renovation Covent Garden. But it was fun too, he assures me.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Large scale, striking & engaging: Mozart's Die Zauberflöte in an historic quarry in Austria (★★★★) - opera review

- Surprisingly, Tannhäuser has received only a handful of

productions at the Bayreuth Festival and this new production by Tobias

Kratzer chalks up its ninth outing -

(★★★★★) Opera review - Prom 34: Schubert, Tchaikovsky, Lutoslawski from Daniel Barenboim, Martha Argerich and West-Eastern Divan Orchestra (★★★★★) - concert review

- A strong message on anti-semitism: Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg at the Bayreuth Festival (★★★★★) - opera review

- Helen Habershon: Found in Winter (★★★) - CD review

- Prom 26: Mozart's Requiem, Brahms and Wagner from BBC National Orchestra of Wales (★★★) - concert review

- A stupendous achievement for a small opera company: Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg from Fulham Opera (★★★★) - opera review

- Exciting, colourful & a challenge: Clarinettist Mark van de Wiel talks about Joseph Phibbs' new concerto which he premiered & has just recorded - interview

- Strip Jack Naked: Stephen McNeff's music theatre piece for Lore Lixenberg (★★★★) - CD review

- Tête à Tête: dance, Chinese folk tales, and the Apollo Mission to the moon - opera review

- Tête à Tête: Yolande Snaith, Roswitha Gerlitz & Kris Apple's Of Body and Ghost, and Alastair White's ROBE - opera review

- Bewitched, bothered and bewildered: Mozart's The Magic Flute broadcast from Glyndebourne (★★★) - opera review

- More than just a stepping stone: Marschner's Hans Heiling in fine new recording from Essen - (★★★★) CD review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment