|

| Soprano Caroline Branchu as Julia in Spontini's La Vestale |

Gaspare Spontini was born in 1774 and trained at one of the conservatories in Naples, and his early career was in Italy where he wrote ten operas. Travelling to Paris in 1804, he had success with his Italian comedies and wrote three French comic operas. But he came to the attention of the Imperial court and in 1805 was made compositeur particulier de la chambre to Empress Josephine. This is where some of Spontini's ill-luck comes in, because his two major operas La Vestale and Fernand Cortez would be strongly identified with the Napoleonic regime.

La Vestale was written in 1805 evidently with the encouragement of the Empress. It seems to be Spontini's first serious opera and is a three-act tragédie lyrique where Spontini's admiration for the French operas of Gluck shines through. It wasn't premiered at the Paris Opera until 1807 because of politicking and it was thanks to the Empress' support that it was finally performed. The highly regarded libretto was by the French dramatist Étienne de Jouy, who would go on to write librettos for Rossini (Moïse et Pharaon in 1827, Guillaume Tell in 1829). La Vestale ran for a hundred nights and, owing in part to its libretto, was characterised by the Institut de France as the best lyric drama of the day. In the title role was the French diva of the period, Caroline Branchu who sang in both Spontini's Fernand Cortez and Olimpie, and who was briefly Napoleon's mistress. There is also a suggestion that contemporary audiences would have identified Licinus, the Roman general hero, with Napoleon.

Hugely admired by his contemporaries, not just Berlioz but Wagner, the opera's Gluckian classicism has meant that it struggles somewhat in the present day and like Cherubini's Médée (which premiered in Paris in 1797), La Vestale has been reliant on a leading soprano to champion it, notably of course Maria Callas. And like Médée, La Vestale has become better known in its Italian translation, though French versions are becoming more common. The opera perhaps also suffers because the plot (about a vestal virgin who transgresses on her vows) is a bit too reminiscent of Bellini's Norma. There have been historically informed performances of the La Vestale (the work was conducted by Jérémie Rhorer at Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in 2013 with Ermonela Jaho in the title role, see on-line review, which was the work's first staging in Paris for 160 years!). But none has made it to disc so that if you are interested in hearing the original French version then the choice inevitably falls on Riccardo Muti's 1993 recording from La Scala, Milan with no Francophone singers in the cast.

The work is being given in concert next June at Théâtre des Champs-Elysées with Christophe Rousset conducting Les Talens Lyriques with Marina Rebeka and Stanislas de Barbeyrac as Julia and Licinus, see the theatre's website.

|

| Gaspare Spontini |

The premiere of Fernand Cortez was not unproblematic and Spontini evidently kept tinkering with the work, which was challenging for singers and orchestra. But with the failure of the Spanish campaign in 1812, Napoleon ordered the opera's removal from the stage, though it had already been performed in Vienna, Berlin and Budapest. But then it disappeared.

Fernand Cortez might simply be an intriguing political footnote in musical history if the opera wasn't so important and so influential. Essentially, Spontini and De Jouy seem to have invented the genre of French Grand Opera, avant la lettre. Here we have a grand historical subject (rather than something mythological or set in the ancient world), two characters from opposing sides whose love is set against conflict (here the Spanish invader Cortez and the Aztec princess Amazily), the conflict between public duty and private desires, the use of religion as the backdrop, the extensive use of the chorus, ballet and large-scale scenic effects. French Grand Opera would very much be a product of the France of the 1820s and 1830s, but Fernand Cortez showed the way.

With its element of political propaganda for a failed campaign by a failed ruler, Fernand Cortez could not stand as it was and Spontini made wholesale revisions, moving whole sections and introducing a major new character, to create a revised version of the work which was presented in Paris in 1817. It was well received and remained in the repertoire for 20 years, reaching 225 performances. He would revise it again for Berlin in the 1820s and when in 1840 the Paris Opera planned to perform it, Spontini wanted to revise it again (they seem to have ignored him and performed their traditional 1817 version).

It is in the 1817 revised version that the work has become known, but it is the original which has the most dramatic cogency. Shorn of his 1809 quasi Napoleonic role, the figure of Fernand Cortez becomes something of a cypher in the 1817 opera. We can now see this for ourselves as the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino performed the work in 2019 in the 1809 version (based on a new critical edition) and conducted by Jean-Luc TIngaud this is now on DVD [Amazon], with a largely Italian-speaking cast singing in French. The opera is not unproblematic for 21st-century audiences, the depiction of the Aztecs as bloodthirsty savages who need civilising is a tricky one, and you suspect the opera will always remain on the fringes, however its importance in 19th century France and Germany cannot be overstated. The young Richard Wagner would see the opera in Berlin and it would be one of the inspirations for his own French Grand Opera-inspired work, Rienzi.

|

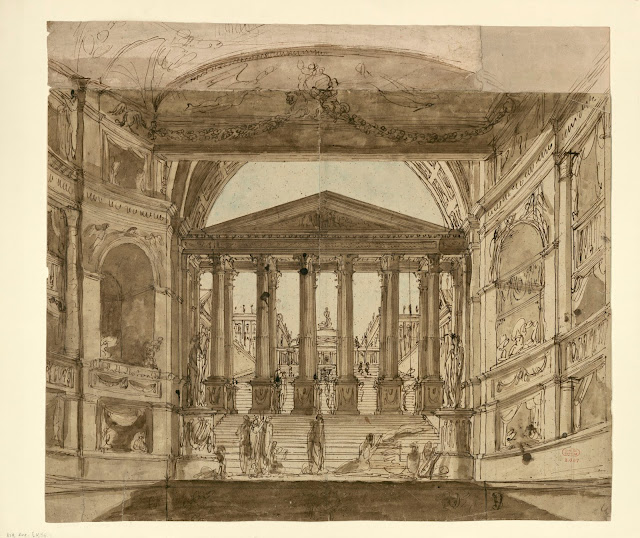

| Sketch by Ignazio Degotti of the décor for Act 1 of the 1819 production of Spontini's Olimpie in Paris |

Spontini's final work for the Paris Opera was Olimpie, based on a play by Voltaire. In its classicism, the setting is just after the death of Alexander the Great, the work seems a step back and the temple setting rather evokes Gluck's Iphigenie en Tauride (premiered in Paris in 1779). Yet Spontini would carry over his large-scale use of chorus from Fernand Cortez, as well as writing for a huge orchestra and including spectacular scenic effects (at the work's Berlin premiere Cassandre rode in on a live elephant).

The work was not well-received (very much mixed reviews) and it was withdrawn after seven performances. Part of the problem was perhaps the work's subject matter. For all the spectacular effects, neo-classical subjects were on their way out, but also Spontini was inevitably linked closely to the previous regime.

This was the period of the Bourbon Restoration, which lasted from the fall of Napoleon in 1814 to the July Revolution in 1830 (with an interregnum of Napoleon's 100 days in 1815). It is this period that sees the rise of French Grand Opera, as the bourgeois audiences become more important and the Paris Opera sought new ways to attract and entertain. Opera was no longer the preserve of the elite aristocrats knowledgeable about the classical world, the works needed to be more immediate. This gives us something of the background to Olimpie, and helps explain why Spontini, as a composer intimately linked to Napoleon's regime, struggled to capitalise on the changes.

Luckily for Spontini, in the audience for Fernand Cortez in 1817 was King Frederick William III of Prussia, who was struck by the music's power and offered the composer the post of General Musik-Direktor in Berlin. Spontini would be there from 1820 to 1840, would oversee new versions of both Olimpie and Fernand Cortez (in German). In fact, the German version of Olimpie, with a text translated and revised by the German Romantic author E. T. A. Hoffmann, was so successful in Berlin in 1821 that a new French version was produced based on this and given in Paris in 1826 when it was again met with indifference despite a new happy ending. Olimpie has been recorded in a scholarly historically-informed fashion by Palazzetto Bru Zane (see my review), but we are unable to compare versions as only the final version seems to survive.

|

| Dario Schmunck in the title role of Spontini's Fernand Cortez in Florence in 2019 (Photo Michele Monasta) |

When you look at Spontini's mature catalogue (the Wikipedia page is excellent ) you can grasp why his mature output is so small, Fernand Cortez went through four versions, Olimpie through three and his final opera, Agnes von Hohenstaufen through three. He seems to have been a compulsive reviser!

Premiered in 1829, Agnes von Hohenstaufen came just six years after Weber's Euryanthe [see my article] and exists in a similar historical-romantic world with its setting in Germany in the Middle Ages, though undoubtedly Spontini brings elements of French Grand Opera too. Most modern revivals of the work have been in Italian and that is the only way you can experience it on disc, though there have been performances of the work in its original language in Germany. It was given in German for the first time since the 19th century in Erfurt in 2018.

Spontini's time in Berlin was soured by his relations with Meyerbeer. Berlin-born, Italian-trained, Paris-based, Meyerbeer remained true to his native city and had a court appointment from 1832. But Spontini, as director of the Court Opera, seems to have dragged his feet over the premiere of Meyerbeer's 1831 opera, Robert le Diable, but censorship also prevented Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots from being performed. Finally, in 1841 a new Prussian king, Frederick William IV was more liberal, Spontini was replaced by Meyerbeer as director of the Court Opera, Les Huguenots received its Berlin premiere, and Spontini returned to Italy, where he died in 1851.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

- A strong affinity for Russian music: I chat to pianist Sonya Bach about her recent Rachmaninov disc, studying with Lazar Berman and more - interview

- Engaging, imaginative and beautifully thought out: four online recitals from Robin Tritschler, Jess Dandy, Julien van Mellaerts, Harriet Burns and Ian Tindale - online review

- American Quintets: Kaleidescope

Chamber Collective's debut recording features the 1st recording of a

mature Florence Price work alongside Amy Beach and Samuel Barber - record review

- Piazzolla explorations: celebrating the composer's centenary with recordings from Lithuania, Switzerland and the USA - record review

- Janacek's The Diary of One Who Disappeared alongside his Moravian songs and Dvorak's Gypsy Songs from Nicky Spence, Fleur Barron, Dylan Perez and friends at Opera Holland Park - concert review

- A light touch, yet full of character: Mascagni's L'amico Fritz proves an engaging discovery at Opera Holland Park - opera review

- To focus on the journey, on the people and their stories: Julia Burbach directs Wagner's Die Walküre for the Grimeborn Festival - interview

- Janacek's forest could easily be on a London estate around the corner from the theatre: The Cunning Little Vixen at Opera Holland Park - opera review

- The piece conveys the idea that women should be listened to: composer Gráinne Mulvey & soprano Elizabeth Hilliard chat about their latest collaboration Great Women - interview

- Seven Ages: Mark Padmore, Roderick Williams, Julius Drake, Victoria Newlyn at Temple Music - concert review

- The Call: six young artists showcased in the first recital disc from Momentum - record review

- Encounters: York Early Music Festival with Tudor motets, Elizabethan viol music, baroque cantatas and the madrigal re-imagined - review

- Young contemporary composers to late Haydn: London Oriana Choir at Opera Holland Park - concert review

- Home

.jpg)

I have an old (ancient!) Cetra-Soria LP recording of La Vestale with Maria Vitale and Renato Gavarini, conducted by Previtali.

ReplyDelete