|

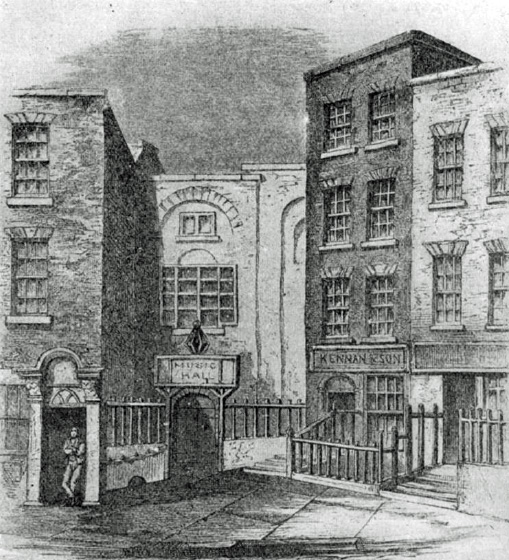

| The Great Music Hall in Fishamble Street, Dublin, where Messiah was first performed in 1741 |

Handel Messiah; Harriet Eyley, Jess Dandy, Stuart Jackson, James Newby, Choir of Jesus College, Cambridge, Britten Sinfonia, David Watkin; Barbican Centre

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on 17 December 2021 Star rating: (★★★★½)

A team of young soloists and a young choir in a performance that relished the litheness of the instrumental forces and reinforced the real message of Charles Jennens' selection of texts

Feeling like something of a little miracle in its own right, Britten Sinfonia brought their performance of Handel's Messiah to the Barbican on Friday 17 December 2021 (the second of three performances in Norwich, London and Saffron Walden). David Watkin conducted the Britten Sinfonia and Choir of Jesus College, Cambridge (director Richard Pinel who played the organ in the performance) with a fine team of young soloists Harriet Eyley (soprano), Jess Dandy (contralto), Stuart Jackson (tenor) and James Newby (baritone).

We heard the familiar Watkins Shaw edition, and there were cuts (four numbers in Part Two, and three numbers in Part Three), bringing the performance in at a little over two hours 30 minutes. The whole had a compact, lithe feel to it with the Britten Sinfonia fielding eleven strings (led by Thomas Gould) and the choir of Jesus College (with women and men) fielding 25 singers. All clearly relished the clarity this brought and there was a vivid litheness to the orchestra's playing that never felt underpowered, quite the opposite in fact as with out the luxuriant sheen of myriad strings the result had a strength and vibrancy. From the opening notes of the overture, it was clear that whilst that was an historically inspired performance the players were intelligently in the modern era, with fine phrasing and articulations to suit the instruments.

I was heartened to see Britten Sinfonia using a team of talent young artists rather than reaching for the familiar, distinguished older faces. All four singers brought something special to the performance, each strongly characterised their music. But it was as if they had got together at the beginning and decided that the most important thing was the text and its message. This is entirely true, of course, Charles Jennens' assemblage of Bible texts for Messiah had a didactic purpose, the idea of bringing the word to people in the concert hall.

From the first notes of tenor Stuart Jackson's recitative, 'Comfort ye', it was clear that he was propounding the words, conveying the meaning of the libretto; you felt he believed them and was intent on us doing so too. So that we moved from the controlled power of the recitative to the real joy of 'Comfort ye', with terrific runs. Here and during the rest of the piece, Jackson gave a strong sense of the religious comfort the words were meant to bring.

For the sequence of recitatives and arias in Part Two, Jackson moved from trenchant words, to compelling drama in 'Behold, and see', and a sense of joy, with terrific articulation' in 'But Thou didst no leave'. For his final aria in Part Two, Jackson's strength was mirrored by the strings who were really digging in; terrific.

Baritone James Newby's opening recitative, 'Thus saith the Lord' was similarly very text based with a great sense of drama, and terrific runs too conveying emotion and meaning. And his second recitative, projecting a definitive message, led to the contained yet compelling 'The people that walked in darkness'.

In Part Two, 'Why do the nations' was vivid with fine, fluent runs, then in Part Three he moved from mystery in the recitative, a clear story to tell, to focused power and strength in 'The trumpet shall sound' complemented by Imogen Whitehead's fine trumpet playing, a real duet.

Jess Dandy has that relatively rare voice nowadays, a fine contralto instrument with superb lower register (which is not to imply that her upper is not lovely too). 'But who may abide' combined fine phrases with well shaped words. Throughout the work Dandy combined a sense of dignity with a feeling of quasi-operatic drama, very much demonstrated in 'he shall feed his flock'. 'He was despised' was serious yet fluid, with shapely phrases and rich dark tone; moving yet modern feeling in tone.

Handel makes us wait for the soprano entry, saving her for the super recitative sequence around the Shepherds, and Harriet Eyley did not disappoint. She has a warm, vibrant voice and used this to fine effect in creating a sense of drama here. 'Rejoice greatly' was crisp, articulated and vital, whilst her final aria in Part One was serious and intent.

She made 'How beautiful are the feet' quite serious yet with a nice lilt to it, whilst in Part Three 'I know that my Redeemer liveth' was firm with a strong sense of purpose. And the soprano has the final aria, and Eyley was warm and considered in 'If God be for us'.

The chorus brought a bright, youthful sound to the mix, lovely clarity in the faster choruses and a sense of commitment and drama. There was never any feeling of 'Oh Lord, here we go with Messiah again', they seemed wonderfully involved. David Watkin's speeds were sometimes fluent and he kept the piece moving, but you never felt anything was too fast. There was, thank goodness, never a sense of look at us, how clever the chorus is at singing very fast.

This was a wonderfully engaged and engaging performance. It evoked the sort of smaller scale Messiah that Handel might have recognised, but with a modern exploration of the music and its meaning.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Something more raw, that goes back to the origins of the stories: I chat to composer Glen Gabriel about his new album, Norse Mythology - my interview

- The comfort of the familiar mixed with the intriguing, the lesser known and the downright unfamiliar: The Sixteen at Christmas - concert review

- Poetic imagination: Andri Björn Róbertsson and Ástríður Alda Sigurðardóttir in songs by Árni Thorsteinson & Robert Schumann - record review

- Bird Portraits: Edward Cowie's amazing musical exploration of birdlife - record review

- Meyerbeer's first opera, written when he was just 21, is finally available in a modern recording that enables us to begin to appreciate what we've been missing - record review

- Celebrating the 300th anniversary of their publication in 1720, Bridget Cunningham records Handel's Eight Great Harpsichord Suites - record review

- A festive feast of Bach for Christmas: Gabrieli Consort & Players at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- Dancing a pas de deux with Tchaikovsky and holidaying in North Africa: rumours swirled around Saint-Saens even before his death - feature

- Being able to see Brahms as he was at the time: I chat to Jérémie Rhorer about recording historically informed Brahms with Le Cercle de l’Harmonie - interview

- La Bonne Cuisine: Lotte Betts-Dean and Harry Rylance at Fidelio Cafe on OnJam Lounge - concert review

- Christmas disc round-up: from Christmas Matins in Bavaria & Nine Lessons & Carols at King's College, Cambridge to festive brass from Canada & the Wexford Carols - record review

- A story to tell: the new recording of Handel's Messiah from Eboracum Baroque - record review

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment