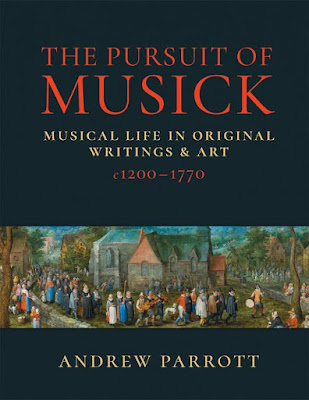

Andrew Parrott's The Pursuit of Musick: musical life in original writings & art c1200-1770, published by Taverner, is a somewhat deceptive book. Its substantial size and generous illustrations seem to suggest a coffee table book, but Parrott's name as the author implies deeper scholarship and you might think it a book of his collected writings. Both ideas are wide of the mark. It is rather an amazing book, full of deep scholarship but without a single word of Parrott's own its 544 pages, apart from the Introduction.

Instead, it is an exploration of music and music's place in society over 500 years looked at through the words and images of contemporaries. In his Introduction, Parrott explains that the book arose originally from a commission for an 'Early Music' book, but that he struggled to bring together original images and modern text. Finally, he dropped the modern text; what we have is a consideration of music using the images and words of the time.

One of Parrott's themes is that music during the period of consideration, roughly 1200 to 1770, is more varied and more surprising than might first be thought. And what better way to explore than to read what others had to say about it. His net is cast very wide indeed, so for instance to take just one section ('Virtues & Vices' within Voices), there is Verelst's portrait of Handel's soprano, Anna Maria Strada, and writings by Jacopo da Bologna (c1350), John Dowland's 1609 translation of Ornithoparcus (1517), Hermann Finck (1556), Giovanni de'Bardi (c1580), Christoph Praetorius (1581), Bacilly (1668), J-J Rousseau (1753), Conrad von Zabern (1474), Zacconi (1592), Tosi (1723), Mattheson (1739), Quantz (1752), Francesco Bagnacavallo (1492, writing to Isabella d'Este), Zaarlino (1558) and John Evelyn (1685).

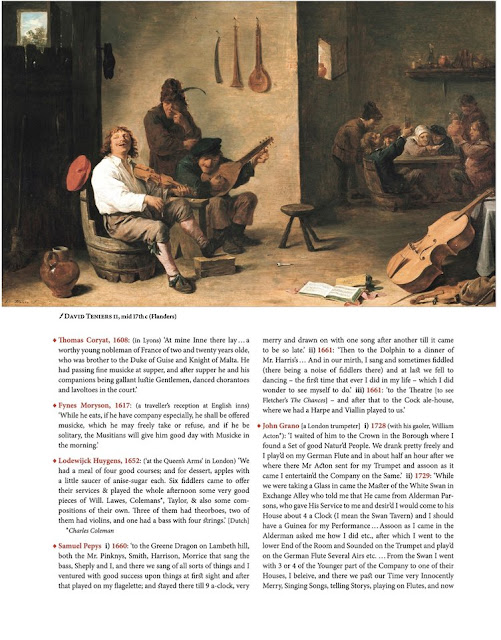

The images are as fascinating as the text and of course, the truism that a picture is worth a thousand words comes to mind. Some I was familiar with, others not - Charles II's private music, ten-year-old Mozart playing whilst Princesse de Conti had tea in Paris. Images of music and performance, performers and theatricality, manuscripts and documents, that all tell us a little about how people thought about music at the time.

The foreign language texts have all been translated, whilst the English texts are left unmodernised. There is a full image list at the back of the book, but full bibliographic information for the texts is held on the Taverner website along with the original language texts.

The book is divided into three parts, Music & Society, Music & Ideas, Music & Performance and within each of these there are thematic sections, up to eight large ones per part plus a far larger number of small ones. So that Music & Performance takes us in detail through voices and classifications, different types of instruments, and performances from voices, and instruments, consideration of improvisation, rehearsals and the composers' intentions, pitch and tuning, tempo and rhythm, and ornamentations, along with 15 shorter sections on everything from obscure instruments such as the bandora to recitative, cadenzas and vibrato. Thus we can get to read Matheson talking about the lute-like calichon used in churches in 1713, Rousseau on vibrato in 1768, 'The undulation that in beautiful voices is constant & moderate makes itself all too evident in voices that are tremulous & feeble', or G. B. Doni on the same subject from his Trattato della musica scenica of 1635, 'this trembling of the voice that some people make (like an imperfect trillo) is not to be used except when the subject matter is low & concerns women'.

Of course, what is equally telling is what is not said. Different eras had different approaches to the same subject, so Egidius de Zamora could write around 1270 'The music of the world is the contemplation by reason of those things which occur in heavens & in the elements and in the changes & alterations of the seasons', and Johannes Kepler wrote in 1619, 'The motions of the heavens, therefore, are nothing but a perpetual harmony (of reason rather than voices) which moves through dissonant tensions'.

The writings on opera include several relating to performances in London, and we learn much about the novelty, and the politics (Lord Hervey on the feud between Cuzzoni and Faustina), but few of the details that we might long for but which, for contemporaries, were rather taken for granted. It is, however, fascinating to read Pierre-Jacques Fougeroux, a French visitor writing in 1728, 'As there is no spectacle at all by way of dances, scenic decoration & stage machinery, and the stage is clear of choruses and that great assemblage of singers who lend dignity to the scene, one may say that the name of opera is wrongly attached to this spectacle; it is rather a fine concert on a stage.'

The book is studied with gems, the Earl of Perth writing of a visit to Cardinal Ottoboni at Albano Laziale near Rome, and hearing Corelli. Perth notes that Corelli was a 'fidler' but waited on Ottoboni as a gentleman, with another musician and three 'eunuchs' sing and play every night 'and nothing can be finer'. This might be from 1695, but it gives us a little window into the world that Handel dropped into a few years later.

Or A. Guidotti, writing in the preface to Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo in 1600, 'to be proportionate to this musical recitation, its [the hall or theatre] capacity should not be more than a thousand persons, who should be comfortably seated, so as to reduce the noise and increase their own satisfaction; since for performances in very large halls, it is not possible to make the words audible for everyone. Hence it would be necessary for the singer to force the voice, and this means that the feeling loses its intensity; without words that can be heard, so much music becomes tedious.' Wonderful words which ought to be remembered more today.

The book's associate editor is Hugh Griffiths, and he has contributed introductions to each of the sections, putting the assembled text and images into context. This form a lucid mini-history of music and society. There are some 560 images (over 300 in colour), and over 2,800 text entries.

This is an amazing book. Not so much one to read from cover to cover as to dip into. But it is also a research tool, a valuable insight into what was important (and what was not important) in music for people in past eras.

Full details of the book from Taverner.org, and it is available online from them for £65 (hardback) and £35 (paperback), which frankly seems like a bargain.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- What came after: Schütz' telling of the Resurrection story in Historia der Auferstehung Jesu Christi proves masterly - record review

- Filmic vividness: Bjørn Morten Christophersen's Darwin-inspired oratorio The Lapse of Time is a complex, large-scale piece of writing - record review

- A joyous Easter celebration from Florilegium at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- A tale of two passions: Sebastiani's St Matthew Passion at Wigmore Hall and Bach's St John Passion at St Martin in the Fields - concert review

- A multiplicity of possibilities: pianist Edna Stern on Bach and the art of Zen - interview

- The sheer sense of engagement from the young choral singers was a joy: Bach's St Matthew Passion from Choir of King's College, London at St John's Smith Square - concert review

- Clarity & suppleness: Frank Martin's Mass & Maurice Duruflé's Requiem from the Maîtrise de Toulouse - record review

- Hindemith & beyond: Trio Brax's debut disc takes the Trio for Viola, Tenor Saxophone & Piano as starting point for an imaginative recital - record review

- Imaginative programme & unusual repertoire: The Fourth Choir's The Only Planet at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse - concert review

- Reclaiming Handel's first thoughts: Peter Whelan directs Irish Baroque Orchestra in the Dublin version of Messiah - concert review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment