Karen Henson; Opera Acts: Singers and Performance in the Late Nineteeth Century; Cambridge University Press

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on Aug 31 2015

Star rating:

Fascinating account of opera singing in the late 19th century, focussing on four key singers and the physicality of their performances

The late 19th century is often regarded as a low-point in operatic singing, the singers falling into a gap between the last generation to work collaboratively with composers (such as Giuditta Pasta with Bellini), and the 20th century singers whose career was defined by the recording process. But I have long been fascinated by such figures as Celestine Galli-Marie who created the role of Bizet's Carmen, about whom a great deal of myth and legend as accumulated, and Jean de Reske whose repertoire ranged from Gounod's Romeo and Wagner's Tristan (in the same season). So I was eager to see this new study in Cambridge University Press's series Cambridge Studies in Opera, Karen Henson's Opera Acts: Singers and Performance in the Late Nineteeth Century in which she explores opera singing in the 1880's and 1890's.

Starting from Verdi's phrase 'not singing' ('che ... non cantasse') which he used about Lady Macbeth, Henson looks at how singers were hemmed by a generation of composers who expected to have a greater degree of control over exactly what the singer did, and so the singers expressed themselves in other ways. By exploring in detail four singers of the period (along with eight 'supporting cast'). Karen Henson looks at how singers used physicality as a way of personal expression. This wasn't naturalism as we think of it, but an emphasis on physicality. The four singers in question each had a major relationship with a contemporary composer, though judging from contemporary reports none of the four had spectacular voices. It was in their physical acting, their presence (singing physignomically in Henson's phrase) that they expressed the drama of the music. The four singers are baritone Victor Maurel who created Iago in Verdi's Otello and the title role in Falstaff, mezzo-soprano Celestine Galli-Marie who created the title role in Bizet's Carmen, soprano Sybil Sanderson for whom Massenet wrote a number of roles including the title role in Thais and tenor Jean de Reske who played an important role in singing Wagner.

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on Aug 31 2015

Star rating:

Fascinating account of opera singing in the late 19th century, focussing on four key singers and the physicality of their performances

The late 19th century is often regarded as a low-point in operatic singing, the singers falling into a gap between the last generation to work collaboratively with composers (such as Giuditta Pasta with Bellini), and the 20th century singers whose career was defined by the recording process. But I have long been fascinated by such figures as Celestine Galli-Marie who created the role of Bizet's Carmen, about whom a great deal of myth and legend as accumulated, and Jean de Reske whose repertoire ranged from Gounod's Romeo and Wagner's Tristan (in the same season). So I was eager to see this new study in Cambridge University Press's series Cambridge Studies in Opera, Karen Henson's Opera Acts: Singers and Performance in the Late Nineteeth Century in which she explores opera singing in the 1880's and 1890's.

|

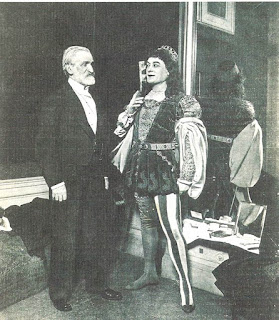

| Baritone Victor Maurel and Verdi |

|

| Sybil Sanderson as Massenet's Esclarmonde |

This is very much an academic book (Karen Henson is Associate Professor at the Frost School of Music, University of Miami), and her writing style reflects this in not always being the easiest of reads, and to appreciate the arguments you have to read copious quotes from contemporary descriptions. But it is worth pursuing, the arguments and information are completely fascinating.

|

| Celestine Galli-Marie as Bizet's Carmen |

Celestine Galli-Marie's role in creating Carmen in Bizet's opera is the stuff of legend, but Karen Henson argues that it was not naturalism/realism that the singer brought to the role but a sense of theatricality. This was based on her background in a performing family (her father was an opera singer, her sisters performed in operetta and cafe-concerts), and a history of intervening visually (costumes, gestures) in the way characters were performed on stage. Interestingly, Celestine Galli-Marie seems to have had quite a light voice, so by the time you have read Karen Henson's chapter on her the image of a Carmen with a rich dark voice and heavily realistic acting is well and truly scotched.

The soprano Sybil Sanderson had a long relationship with Massenet (he had a tendency to become enamoured of female singers and write roles for them). With Sybil Sanderson, Massenet not only wrote the music but seems to have influenced (controlled?) her visual image including numbers cartes de visites. Whilst it is easy to think of Sybil Sanderson as a purely passive receptacle, Karen Hansen argues for her far more active involvement in the visual presentation (of photographs and of the operas).

|

| Jean de Reske as Wagner's Siegfried |

Karen Henson concludes the book with a short look at the careers of Emma Calve (the second Carmen), Victor Capoul Jean-Baptiste Faure, Marie Heilbron, Paul Lherie (the first Don Jose), Paole Marie (Celestine Galli-Marie's sister) and Jean de Reske's siblings, Edouard and Josephine. The result is to provide a fascinating patchwork of image of how singers of the period made their mark in both singing and 'not singing'.

I doubt that this book is the last word on the subject, but it is certainly a fascinating contribution to the debate about singers of the recent past. It is a wonderful corrective to the rose-tinted spectacle view of early performers. Reading Karen Henson really makes you think about what those audiences in the 1880's and 1890's actually heard and saw, and how much control the singer involved had.

Jean de Reske recorded at the Met in New York in 1901 on a Mapleson Cylinder.

Elsewhere on this blog:

- Colour and Drama: Mozart and more from Anneke Scott and Ironwood - CD review

- An Avila Diary: My adventures singing triple-choir music by Victoria and Vivanco under Peter Phillips in Spain - feature article

- Serious, independent, fascinating: Music by Edward McGuire from Red Note - CD review

- Charm: Wolf-Ferrari's Suite Veneziana - CD review

- Undeservedly forgotten: Music by Roger Sacheverell Coke - Cd review

- Wartime consolations: Linus Roth plays music by Weinberg and Hartmann which deserves to be heard

- Towering achievement: Beethoven's Diabelli Variations from Nick van Bloss - CD review

- Family connections: Alissa Firsova Russian Emigres - CD review

- Volume 5 of Malcolm Martineau's survey of Poulenc Songs - CD review

- Contemporary opera is alive and well and living in Kings Cross: Tete a Tete festival - opera review

- New voice from Iceland: Hugi Gudmundsson's Calm of the Deep - CD review

- More than frothy fun: Gluck's Il Parnaso confuso from Les Bougies Baroques - opera review

- Sparkling delight: Wolf Ferrari's Il Segreto di Susanna - CD review

- Of great beauty: Monteverdi's L'Orfeo at the Proms - Opera review

- Dazzling technique, bags of charm: Gallay operatic fantasies from Anneke Scott - CD review

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment