|

| David Matthews (Photo Clive Barda) |

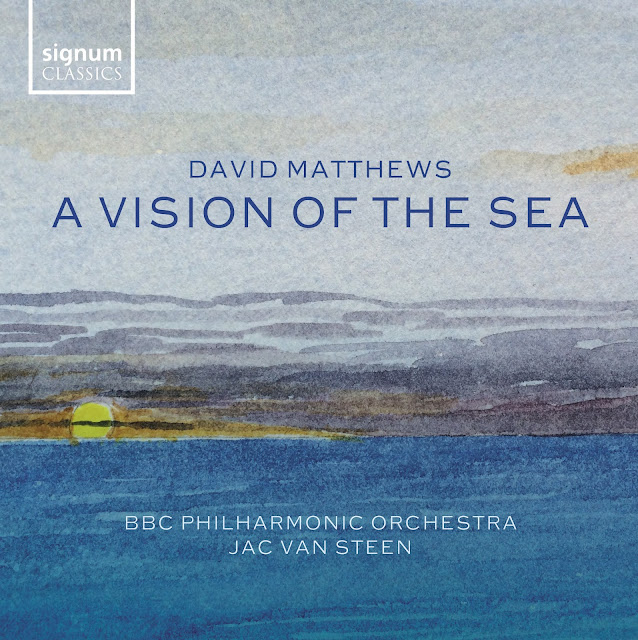

In the programme notes for composer David Matthews' latest disc, he says that he has been 'obsessed with the symphonic form since he was 16' and David wrote a number of discarded symphonies before his acknowledged first (1975-78). For the new disc on Signum Classics, Jac van Steen (who has conducted a number of David's other symphonies on disc) conducts the BBC Philharmonic in his Symphony No. 8, Sinfonia and the symphonic poem A Vision of the Sea.

When I spoke to David recently he admitted that he was currently working on his tenth symphony! (The first nine symphonies are all available on disc, see the list at the foot of this article). But our conversation also ranged widely, covering David's ideas about tonality and traditional symphonic form, the importance of what he learned when working as Benjamin Britten's assistant, David's paintings (one of which is on the CD cover), and writing his first opera.

Whilst David's basic idea of the symphony has not changed too much over the years, he has experimented a little with the form so that some are one-movement works inspired by works such as Sibelius' Symphony No. 7, whilst multi-movement symphonies might be in two, three, four or five movements (Symphony No. 8 is in four movements). David's view of the symphony chimes with the writings of composer Robert Simpson (1921-1997) and writer Hans Keller (1919-1985), whose definition David quotes in the booklet notes 'the large-scale integration of contrasts'. David feels that such a work is the ideal opportunity for a large scale piece. He has never minded that the form is traditional, and in fact feels that this can be beneficial for the audience.

Writing in a traditional symphonic form very much implies the use of tonal centres in the work, and David can think of very few atonal symphonies (except perhaps that of Webern which David describes as 'short and strange'), and most symphonies including those of Shostakovich and Stravinsky use some sort of tonal scheme, as do those of more recent composers such as John McCabe (1939-2015) or Matthew Taylor (born 1964). David adds that whilst the eleven symphonies of Robert Simpson were tonal, the later ones existed on the edge of tonality. David never really moved away from writing musical tonally, and in his symphonies works through tonal centres to achieve something satisfying.

Given David's age (he was born in 1943), this means that he has been very much against the flow of contemporary music. When he was in his late teens he listened to the music of Pierre Boulez (1925-2016) and Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007) and decided that this was not for him. He feels that his music has got more diatonic recently, partly because it has developed that way, and partly because he now feels more able to write diatonically without feeling that he shouldn't!

Perhaps fortunately, David did not go to music college (he studied Classics at Nottingham University), as he knows of contemporaries who were told explicity that they could not write tonal music. At no point in David's lesson's with various composers did any say that writing tonal music was wrong, and in fact it was working with Nicholas Maw (1935-2009), whose music was very much influenced by modernism, that gave David the confidence to write tonally.

David later had a working relationship with Australian composer Peter Sculthorpe (1929-2014), who became a friend and collaborator. Sculthorpe wrote tonal music, though of a completely different type, and David found his view interesting whereby as an Australian he wanted to view European music from the outside. Sculthorpe took the view that most of the world writes tonal music, so why should he be influenced by a few Europeans who do not! Whilst this attitude was one that David found interesting and supportive, he wasn't particularly influenced directly by non-Western music, though he does admit that his String Trio No.2 arises out of his interest in Indian music.

Another composer that David worked with was Benjamin Britten (1913-1976). Britten never took pupils, but David was lucky enough to be able to work with him as an assistant, even though David had no formal musical qualifications. Britten is known for being hard on those who assisted him, but David seems to have satisfied him, and David found it extraordinary to be able to observe Britten in his workshop.

|

| David Matthews |

One thing that David learned from the older composer was the importance of getting works finished on time. Britten was a complete professional and this impressed David, as did the fact that Britten always composed by ear, away from the piano, and only used a piano playthrough afterwards. David always uses a piano for composing, and was heartened when Michael Tippett (1905-1998) admitted to using the piano, saying that his ear was not as good as Britten's. David likes writing at the piano because it means that he can create an entire world of sound around him, though he does not write piano music and then orchestrate it.

In writing tonally, David feels that it is important to renew tonality based on the past, and for much of his career he felt out of touch with what most people were writing, though that has changed. But he also has strong words for some of the more recent composers writing tonally. The Polish composer Henryk Gorecki (1933-2010) and Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (born 1935), David describes as good, genuine and new, but he has found many composers writing in the same vein too simplistic, returning too much to the Middle Ages. For David, it is important to develop the more complex harmonic ideas from the beginning of the 20th century, and he could not give them up.

He comments that he has found that the music of John Adams (born 1947) has got more harmonically adventurous, and that he wrote some wonderful pieces such as Harmonielehre after he broke away from minimalism, Also, David admires Adams for the way the composer has managed to get through to his audience. This is something that few contemporary composers manage to do, and David marvels at the way that the premieres of symphonies by Elgar and by RVW were major events.

Given the relative accessibility of David's musical language, as composer to much of the classical music being written in the later 20th century, I wondered how much David thought of his audience. He is not really aware of the audience when writing, but he is aware of the musicians and he wants them to like playing the music, that is important to him. But having said that, David is hoping to get a reaction from the audience, and would worry if the music did not. But he also comments about some of his contemporaries who write music entirely for themselves without worrying about the audience.

David continues being fascinated by the symphonic form and has recently complete his tenth simphony. This is different again in form, being in one continuous movement made up of linked sections which roughly correspond to the movements but which are also linked thematically. He feels glad to have got over the magic number 10, but is noncommital about an 11th, commenting that he keeps saying enough but carries on.

The album cover of the new disc carries a reproduction of one of David's paintings. His present home is on the Kent coast, and they can see the sunrise on the sea from the house. This has given rise to a number of paintings, and the new album opens with his Towards Sunrise; visual things often suggest music to him. But though he has painted for a long time, he firmly regards it as simply a nice hobby, saying he just does little landscapes and drawings. At secondary school there was no music department, but there was a good art master and David even thought of going to art school and his ambition was to create large-scale oil paintings.

With no music department a school, David's younger brother Colin Matthews (born 1946) was a big influence and the two grew up discovering music together and he feels that he would not have got anywhere in music if both of them had not wanted to compose. They did a lot of music together, with enthusiasms for the same composers, for instance Gustav Mahler, and at the time did not realise that this was unusual. They have now, to a certain extent, gone their separate ways; they deliberately try to avoid being too close, not having pieces in the same concert and not writing for the same people. Also, David sees Colin as the more modernist. Colin met Elliott Carter (1908-2012) and was very influenced by him, and was close to Oliver Knussen (1952-2018). Yet they still respect each other's music.

The two have also collaborated on projects and recently orchestrated a group of songs by Alma Mahler. For this sort of collaboration they work separately and then look at the results together. And they have also completed orchestrating a group of songs by Gustav Mahler (Alma's husband) which the two started when still in their teens, and the two assisted Deryck Cooke (1919-1976) with his completion of Mahler's Symphony No. 10. [You can read David's thoughts on the symphony on the Colorado MahlerFest website]. When orchestrating like this, David tries to stay loyal to the original composer's style, to attempt to do what they would have done. David has completed an unfinished cello concerto by RVW, Dark Pastoral. To do so he had to get in the mood to write it and 'become RVW for a bit', and people do not notice where the join is. David has also written a Norfolk March inspired by an RVW work (the Norfolk Rhapsody No. 3 from 1906) which has been lost, basing his work on the folk-songs that were known to be in the original and on the programme note for the premiere of the work.

Looking ahead, he has an organ piece for Hansjörg Albrecht who is recording all of Bruckner's symphonies in transcriptions for organ, on Oehms Classics, and Albrecht has commissioned a new piece to go with each symphony. David is writing something to go with Bruckner's Symphony No. 2, though he is still awaiting ideas about the shape of the work and its relationship to the Bruckner. It will be premiered on the organ of Westminster Cathedral, which David knows well, though every organ is different so though David does not want to be too specific about registration, he has a certain sound in mind. It is a challenge, and he is looking forward to it.

He has also been asked to re-visit his arrangement of Berlioz' song cycle Les nuits d'été, which had made for the Nash Ensemble, and re-work it for baritone Christian Gerhaher. Though as the new arrangement will be for string sextet, David will be unable to use much of his first version. He loves the piece, and finds the project an interesting challenge, particularly as the new ensemble will have no double bass.

But David's big project is a new opera. His first. There are no definite plans for performance, and most opera companies do not know what the future is. But there was a workshop on Act One last year, and David is hoping for a workshop on Act Two. He has left writing opera rather late, because he never found a subject or a librettist. He started to write one three or four times, but never got very far and unfortunately a commission for New Kent Opera didn't happen because the company folded. The new opera is called Anna and has a librettist by Roger Scruton.

David was happy with last year's workshop and feels that it worked dramatically. For David, getting the timing right is one of trickiest things in the process; an opera needs drama and confrontation, and too often David finds modern operas too static. Each act is around 50 minutes or so, which makes it about the length of Britten's Turn of the Screw.

The libretto was written by his friend Roger Scruton (1944-2020), the philosopher and writer, a not uncontroversial figure. Scruton saw the vocal score to Act One, but unfortunately died before the workshop could take palce,and before David finished Act Two. As well as being a writer and a friend, Scruton was also a composer and his own opera Violet (about the life of Violet Gordon Woodhouse) was premiered by Guildhall School of Music and Drama in 2005. David describes Scruton's libretto as good, and very easy to set.

The subject of Anna came about as both David and Scruton were associated with an underground university which Scruton supported in the Czech Republic before the revolution (Scruton would be expelled from the country in 1985; in 1998 he was awarded the Czech Republic's Medal of Merit (First Class) by President Václav Havel). David ended up teaching music for the university in Brno and met a lot of Czech composers and is still friends with some like Pavel Zemek Novak. Working in Brno was a fascinating experience and David got to know about the life of dissidents and their hopes. The opera takes place 'in an anonymous post-totalitarian state, in the months after the collapse of the former tyrannical power: perhaps Czechoslovakia, Poland or Bulgaria after 1989'. David describes it as a tragic love story (a woman falls in love with the former informer responsible for the death of her father), yet it also expresses hope for the future.

David Matthews' symphonies on disc:

- David Matthews - A Vision of the Sea, Symphony No 8 - Jac van Steen, BBC Philharmonic, Signum Classics - available from Amazon,

- David Matthews - Symphony No. 9, Variations for String Orchestra, Double Concerto - Sara Trickey, Sarah-Jane Bradley, Kenneth Woods, English Symphony Orchestra - available from Amazon,

- David Matthews - Symphony No. 7, Vespers - Katie Bray, Matthew Long, David Hill, John Carewe, The Bach Choir, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra - available from Amazon,

- David Matthews - Symphonies Nos 2 & 6 - Jac van Steen, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Dutton Epoch - available from Amazon,

- David Matthews - Cantiga, September Music, Introit, Symphony No. 4 - Malcolm Nabarro, East of England Orchestra, NMC Recordings - available from Amazon,

- David Matthews -Symphonies Nos 1, 3 & 5 - Martyn Brabbins, BBC National Orchestra of Wales; Dutton Epoch - available from Amazon

- David Matthews - In the dark time, Chaconne - Jac van Steen, BBC Symphony Orchestra; NMC Recording - available from Amazon,

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

- Chemin des Dames: premiere recording of New Zealand composer Gareth Farr's cello concerto, written in memory of his great-uncles killed in the First World War - CD review

- Influence at Court: the sacred music of Pelham Humfrey explored in a new disc from the choir of Her Majesty's Chapel Royal on Delphian - CD review

- A snapshot of the time: Sound and Music (Vol. 1) - CD review

- Bach & the art of transcription:

Benjamin Alard's survey of Bach's keyboard works reaches the late

Weimar period and the composer's discovery of Vivaldi's concertos - CD review

- Sacred Ayres: Psalms, Hymns and Spirituals Songs by contemporary composer Paul Ayres from the chapel choir of Selwyn College on Regent Records - CD review

- The performer is a mirror who should serve the text and the composer: French pianist Vincent Larderet discusses his approach in the light of his recent Liszt recital Between Light and Darkness - CD Review

- Donizetti on the cusp: never a success in his lifetime, Opera Rara reveals much to enjoy in the composer's 1829 opera Il Paria - CD review

- A beguiling disc: Aberdene 1662

from Maria Valdmaa & Mikko Perkola on ERP explores songs from the

only book of secular music published in Scotland in the 17th century - CD review

- Virtuosity and Protest: Frederic Rzewski's Songs of Insurrection receives its first recording - CD review

- Re-inventing Kurt Weill: How

Lotte Lenya's performances of her husband's music in the 1950s, born of

expediency, came to define how the songs were performed - feature article

- Mysteries: Luxembourg-born

pianist Sabine Weyer on how combining music by a Soviet Russian

composer and contemporary French one made a satisfying new disc - Interview

- Home

.jpg)

I enjoyed this overview, thanks. I'm very much enjoying exploring David Mathews's music. Just dialled back to try the very first symphony which actually seems very modernist. His Vespers is extraordinary, and so is A Vision of the Sea. The flute concerto shows a lighter side. I prefer this kind of language to that of Richard Rodney Bennett in his lighter tonal pieces - I feel there is a composer ultimately more compelling in more completely atonal territory (though there are some amazing exceptions like the sax concerto and 16th century variations). But it's important that composers aren't forced to do or avoid anything, they just follow the branches of the tree they are exploring as far as they wish or can.

ReplyDelete