|

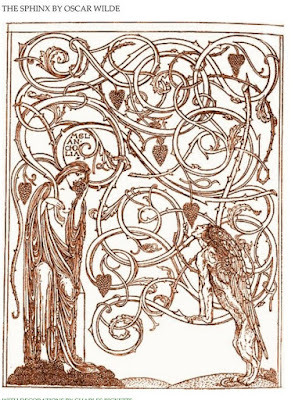

| The title-page of the first edition of Oscar Wilde's The Sphinx with decorations by Charles Ricketts |

Granville Bantock: The Sphinx; Arthur Bruce, Edward Jowle, Simon Butteriss, Nigel Foster; London Song Festival at Hinde Street Methodist Church

Bantock's remarkable large-scale symphonic song cycle on Oscar Wilde's early poem receives a belated premiere in terrific performances from two young baritones

In 1941, composer Granville Bantock (1868-1946) began work on a song-cycle for contralto or baritone and orchestra setting Oscar Wilde's early poem, The Sphinx. The composer was in his 70s and would never hear the work apart from playing the score through to his son and there never seems to have been a performance, in fact Bantock's reasons for setting the poem (to create a large-scale work lasting over an hour) remain obscure.

Dr Andy H King has created a new performing edition of Bantock's The Sphinx and this was the impetus for the work's premiere on Friday 18 August 2023 at the London Song Festival at Hinde Street Methodist Church when pianist Nigel Foster was joined by baritone Arthur Bruce and bass-baritone Edward Jowle. The sections of the song-cycle were interspersed with readings from actor Simon Butteriss in a programme devised by Nigel Foster.

Oscar Wilde began working on The Sphinx in 1874, the year he went up to Oxford and finally published it in a luxe edition in 1894 with illustrations by Charles Ricketts. A 174 line poem, it begins with a 20-year-old student addressing a statue of a sphinx in his rooms, he enumerates scenes from Classical and Egyptian history, asking her if she witnessed them, then he lists her possible lovers, finally deciding on Ammon and goes into some detail on their liaison, before recounting how the splendour as gone to ruin and bidding her return to Egpyt, before dismissing her with disgust.

The poem is a prime example of the Decadent movement, and Wilde's introduction of Christianity into it towards the end as caused much discussion, as well as the poet's references to the sphinx awakening in him 'each bestial sense'.

We have no idea why Bantock wrote the cycle. Frustratingly, there is no information about whether Bantock ever experienced any of Wilde's plays during the poet's lifetime, but we know that later on Bantock read Wilde's plays and three biographies of the poet, and even visited Tite Street where the man lived. Bantock also had a strong interest in Egypt, the Middle East and all things Classical, having written a song cycle based on Sappho, a choral symphony based on The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam amongst other things.

Though Bantock breaks The Sphinx into 12 movements, these are not conventional songs and even with piano accompaniment the work came over as symphonic in scale. Arthur Bruce and Edward Jowle shared the duties, each bringing a remarkable commitment and sense of identification with the poet narrator, and both had very fine diction so that Wilde's words came over well. The poem is essentially an excuse for lists of things, exotic things, wonderful obscure words and throughout the performance you sensed not just Wilde relishing these texts, but Bantock too as he set the phrases with declamatory clarity so we caught every word. And both Bruce and Jowle clearly relished that delight too. It was an evening of gloriously overdone texts such as 'odorous with Syrian galbanum and smeared with spikenard' or 'the Titan thews of him who was thy Paladin', though my favourite remains 'I weary of your steadfast gaze, your somnolent magnificence'.

The symphonic proportions of the work meant that Nigel Foster's role was far more than to accompany the singers, there was a glorious prelude and postlude along with numerous symphonic interludes. Bantock's style was late-Romantic, but within these limits there were moments when the composer was more daring, particularly in the final third when the poet is more dramatic and the lists of exotic things draws to a halt. Whilst there were big moments, there were plenty of places where the writing was spare and you sensed Bantock pushing boundaries in terms of harmony and writing.

The exotic was a constant theme, sometimes just in terms of the writing in the piano and sometimes in the voice as well. Not a re-creation, but simply as one colour amongst many. The work seems to have been written as one long free-flowing exploration, a journey along the text, rather then set formal structures.

The ending was perhaps the most striking, first a movement of intense drama with Bantock's music more daring, Edward Jowle terrific in his declamation and having his every bestial sense awoken. Then Arthur Bruce equally terrific in a final movement of stark drama, but then Bantock had a final surprise a long and surprisingly consoling instrumental postlude.

This was a terrific performance of a truly remarkable piece. We are now sufficiently distant from the 1940s to be able to accept Bantock's music for what it is and not worry about his somewhat old-fashioned approach. Even divided between two young singers, this was a lot of work and both sang with clarity, lyricism and a wonderful identification with the poetic narrator, and neither gave any sense that this was a premiere, that they had never encountered the music before. And at the piano, Nigel Foster was a tower of strength, conjuring some remarkable sounds from a piano part that was intended to evoke the orchestral original.

Nigel Foster had decided to break the cycle up and parallel the narrative arc of the poem with a similar narrative arc where, using Oscar Wilde's own writings, transcripts of his trials and the words of others, Simon Butteriss vividly conjured the progress from a description of Wilde at the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest to the trial judge's terrifying words to Wilde's own poignant acceptance. Perhaps what was scariest was the Marquess of Queensbury's letter to his son Lord Alfred Douglas (Bosie), this was so vicious as to be funny, yet Queensbury clearly meant every word.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- There is a lot going on in what is a relatively short opera: John Wilkie on directing Giordano's opera Fedora at IF Opera with a fantastic young cast - interview

- Joel Lundberg's Odysseys and Apostrophes with pianist Kalle Stenbäcken - record review

- Shot through with sheer delight & joie de vivre: the sounds of 1840s Copenhagen from Concerto Copenhagen as the perform music by 'The Strauss of the North' - record review

- London, ca.1740: Handel's musicians - wonderfully engaged performances from La Rêveuse as they explore works by the musicians of Handel's orchestra - record review

- Still a classic after all these years: Peter Hall's production of Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream at Glyndebourne is in strong hands in the latest revival, conducted by Dalia Stasevska - opera review

- Tales of Love & Enchantment: exploring the delightful songs of contemporary French composer Isabelle Aboulker at the London Song Festival - concert review

- Small but fierce: I chat to Cameron Menzies, artistic director of Northern Ireland Opera - opera review

- Ruddigore: Gilbert & Sullivan's supernatural Gothic melodrama at Opera Holland Park - opera review

- Handel's Attick: music for solo clavichord - A subtle and revelatory disc from Julian Perkins - record review

- Prom 31: Glyndebourne Opera's production of Poulenc's Carmelites, a gripping performance triumphs over unfair acoustic and theatrical compromises - opera review

- Prom 27: eclectic mix - Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini & Walton's Belshazzar's Feast - concert review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment