|

| Wagner: Rienzi - Last scene of Act3 at the Théâtre Lyrique, Paris in 1869 |

Wagner and French Grand Opera

The French Grand Opera was a significant musical influence on the young Richard Wagner, however it was a genre filtered through the works availble to him in Germany. So that, though the operas of both Daniel Auber and Giacomo Meyerbeer seem to have had a big influence, Rossini's Guillaume Tell appears never to have been in Richard's repertoire as a conductor and there is no record of him encountering it in the theatre.

In 1833 Wurzburg Theatre staged Giacomo Meyerbeer's Robert le Diable, it was the operatic event of the year. Richard Wagner's brother Albert was singing the title role and had managed to get Richard a job as chorus master at the theatre. 20-year-old Richard rehearsed the choruses of Meyerbeer's opera and this first exposure to the piece made a big impression on him. Another notable opera that Richard rehearsed was Auber's La muette de Portici. Richard would return to Meyerbeer when he worked in Magdeburg (1834 to 1836) and in Riga (from 1837).

|

| Edgar Degas : Ballet of the Nuns (1876) - from Meyerbeer's Robert le diable |

Richard and his wife Minna (an actress whom he had met whilst working in Magdeburg) ran up such huge debts in Riga that they had to flee creditors. The sea voyage that they took would ultimately inspire Richard's opera The Flying Dutchman, and whilst they were crossing France, Richard met a Mrs Manson who was friendly with Meyerbeer. She gave Richard a letter of recommendation.

Richard had seen Gaspare Spontini's opera Fernand Cortez (one of the important pre-cursors of French Grand Opera) in Berlin, and whilst in Riga, Richard conceived of a grand opera inspired by Fernand Cortez, to his own libretto after Edward Bulwer-Lytton's 1835 novel, Rienzi, the last of the tribunes. Rienzi was intended to provide Richard with a success in Paris, it was written in a style which Richard calculated to appeal to the Paris Opera. And it was Rienzi that Richard hoped to interest Meyerbeer in.

Richard Wagner and Giacomo Meyerbeer

Arriving in Boulogne-sur-Mer, Richard Wagner had Acts One and Two of Rienzi drafted and orchestrated. Richard presented himself to Meyerbeer who listened to parts of Rienzi, invited Richard to supper and to private parties, and provided Richard with letters of recommendation to the Paris Opera's director and its principal conductor. It wasn't that Richard wanted to write only French opera, but he saw no reason why he could not get success writing French opera for the French and German opera for the Germans.

The Paris Opera was effectively a government department and was the centre of operatic life. The company had been founded by Louis XIV and despite numerous regime changes (and name changes), was still in existence. When Wagner arrived in Paris it was known as the Académie Royale de Musique and performed in a theatre on the Rue Le Peletier (where the present Opéra-Comique now is).

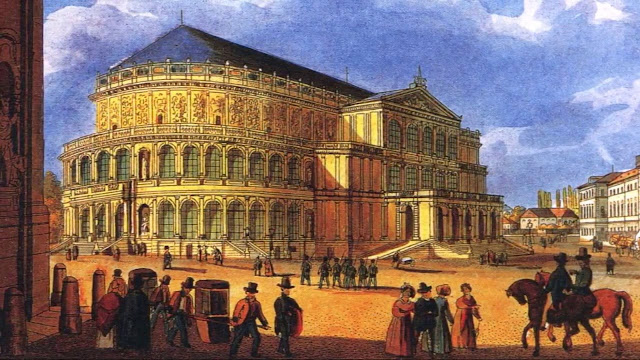

|

| The Théâtre de l'Académie Royale de Musique, the official title of the Paris Opera ca. 1821 |

Life in Paris was expensive and the musical atmosphere there not kind to a young (27 year old) German composer with high expectations. He failed to get work as a conductor, and earned money writing articles and copying scores. Writing to Eduard Hanslick in 1849, Richard said that without Meyerbeer 'My wife and I would have starved in Paris'. And Meyerbeer continued his support, he recommended Rienzi to Dresden, and in 1841 he recommended The Flying Dutchman to Berlin.

Wagner and Meyerbeer in Germany

Rienzi would be produced at the Königliches Hoftheater, Dresden in 1842, to thunderous applause. The opera lasted six hours! The Flying Dutchman was accepted by the Intendant in Berlin, but he promptly relinquished his post, there was no production. The Flying Dutchman would be premiered in Dresden in 1843 with Wagner conducting. When Robert Schumann heard The Flying Dutchman in 1843 he commented to Richard on the 'unmistakeable echoes of Meyerbeer'. Richard reacted with bitterness, he could never draw inspiration from that source 'the merest smell of which, wafting in from afar, is sufficient to turn my stomach'.

The success of Rienzi, the first success that Richard Wagner had had, was crucial to his career and it would go on to be received with critical acclaim in performances across Europe including Vienna, and Paris at the smaller Théâtre Lyrique (rather than the Paris Opera) where it was sung French. Georges Bizet was present at the dress rehearsal and wrote of it to a friend:

"Work badly constructed. A single role: that of Rienzi, remarkably played by Monjauze. An uproar, of which nothing can give an idea; a mixture of Italian themes; peculiar and bad style; music of decline rather than of the future. Some numbers detestable! some admirable! on the whole; an astonishing work, prodigiously alive: a breathtaking, Olympian grandeur! inspiration, without measure, without order, but of genius! will it be a success? I do not know!—The house was full, no claque! Some prodigious effects! some disastrous effects! some cries of enthusiasm! then doleful silence for half-an-hour."

Whilst Rienzi was Wagner's biggest operatic success during his lifetime, he excluded it from the canon of works to be performed at the Bayreuth Festival Theatre, and during the 2013 Wagner Centenary it was performed at the festival for the first time, but not in the festival theatre. Nowadays, Rienzi still receives occasional revivals and you can read about the 2019 revival of Philipp Stölzl's production at the Deutsche Oper, Berlin on Bachtrack, with Torsten Kerl in the title role, conducted by Evan Rogister (and see image below).

|

| Königliches Hoftheater, Dresden in 1850 |

When Richard wrote Tannhäuser in 1845, his experience of French Grand Opera was still recent enough for it to have a big influence on the structure of the piece, and even in the 1861 version (created for Paris), the work's roots in Meyerbeer, Halevy and Auber's La muette de Portici are still detectable. Wagner's opera Lohengrin had its premiere in 1850 in Weimar, conducted by Franz Liszt. Even in this opera, in Act Two, the broad contours of the act could be re-imagined through the formal lens of librettist Eugene Scribe. And in Gotterdammerung (completed in 1874, but based on the libretto Siegfried's Tod written in 1848), there is still a distinctly grand opera cut to the opera.

Wagner in Paris

Having played a minor supporting role in the 1849 revolution in Dresden, a warrant was issued for Richard’s arrest, and he fled Germany. He returned to Paris in 1850 to importune the Paris Opera again (thanks to money from his friend Franz Liszt). Little had changed, his old debts were still there, and doors did not magically open. The Paris Opera was dominated by Meyerbeer's Le prophète (which had premiered in 1849), Richard attended a performance and reported 'feeling physically sick'.

|

| Poster for first Paris production of Wagner's Tannhäuser in 1861 |

Richard had created a new version of Tannhäuser for Paris, this had been requested by Emperor Napoleon III at the suggestion of Princess Pauline von Metternich, wife of the Austrian ambassador to France. This meant inserting a ballet, Richard however put it in Act One rather than the traditional Act Three. The unpopularity of the opera was partly due to the placing of the ballet, but Princess Metternich and Austria were also unpopular as was the Emperor's pro-Austrian policy.

The failure of Tannhäuser put back the cause of Wagner's opera in Paris, so that Lohengrin would not be performed in the French capital until 1891.

Wagner, Meyerbeer and anti-semitism

Richard's attitude to Meyerbeer was complex and changed over time, coloured by his envy of the success of Le prophète and his own sense of indebtedness to Meyerbeer ('biting the hand ....'), and of course, anti-semitism. The significant success of Le prophète came at a time when Richard was still struggling to achieve the recognition he wanted, yet Meyerbeer was of a previous generation (nearly 20 years older than Richard) and Le prophète was conspicuously old fashioned.

By the time of the publication of Richard’s expanded version of his essay Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness in Music) in 1869 (it was originally published anonymously in 1850), Richard’s anti-semitic attitudes were confirmed and the music of Meyerbeer became part of the problem rather than a potential solution, something he had raised (without the anti-semitism) in his 1852 essay Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama). In Oper und Drama, Richard would give an extended attack on the music of Rossini and Meyerbeer, whom he regarded as betraying art for public acclaim and commercial success; it was here that he described Meyerbeer's operas as 'effects without causes'.

Richard's 1850 version of Das Judenthum in der Musik, which attacks both Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn, was perhaps triggered by the death of Mendelssohn in 1847 and by the success of Meyerbeer's Le prophète in 1849. The essay had a very tiny circulation and was published anonymously. However in 1869, Richard revisited it and published it under his own name in an expanded form. The reasons for this revision and publication are unclear and even his supportive wife Cosima doubted that the publication was wise.

|

| Wagner's Rienzi at the Deutsche Oper, Berlin in 2019 (Photo Bettina Stöß) |

Meyerbeer, Wagner and Verdi

1 - The most successful opera composer of the 19th century? - Meyerbeer and his operas

Elsewhere on this blog

- Everything comes from the words: composer Ian Venables talks about his approach to song writing - interview

- The 17th century opera by an Italian composer, premiered in Vienna with a Spanish libretto: Antonio Draghi's El Prometeo - CD review

- Exquisite sketches: songs by Reynaldo Hahn from Anastasia Prokofieva & Sergey Rybin on Stone Records - L'heure exquise - CD review

- Not just Monteverdi's teacher: the choir of Girton College, Cambridge explores the sacred music of Marc'Antonio Ingegneri - CD review

- The Other Cleopatra: Queen of Armenia arias by Hasse, Gluck and Vivaldi from Il Tigrane - CD review

- The most successful opera composer of the 19th century? A look at Meyerbeer and his operas - feature article

- A new recording of Handel's first version of Messiah (Dublin 1742) with a largely German speaking cast - Cd review

- Filling an important gap: the sacred music of Henry Aldrich,

Oxford divine and contemporary of Purcell, performed on Convivium

Records by the Cathedral Singers of Christ Church, Oxford - CD review

- A dialogue with the past: the chamber music of Riccardo Malipiero from the Rest Ensemble - CD review

- Sullivan at his peak, but without Gilbert: Haddon Hall gets its first professional recording - CD review

- A major addition to the symphonic repertoire: Erkki-Sven Tüür's Symphony No. 9 ;Mythos', commissioned for the centenary of the Republic of Estonia - CD review

- All opera is community opera: I chat to director Thomas Guthrie - interview

- Home

%20and%20kids.jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment