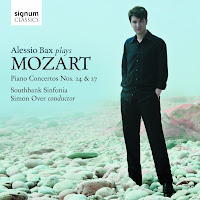

I have to confess that when this disc dropped through my letter-box I did not immediately think, Oh goodie, Mozart piano concertos. Yes, I was interested in Alessio Bax, the young Italian born, USA based pianist and the Southbank Sinfonia under their conductor Simon Over. But Mozart piano concertos? I heard quite a number in the 1980's when I attended the concert series given by the Halle in Manchester and then by the Scottish National Orchestra in Edinburgh, where the concertos were something of a staple in the concert programmes. Whilst I have come to love many aspects of Mozart's music, his piano concertos are still something of a puzzle, and this review is by way of an exploration.

Mozart wrote his Piano Concerto no. 24 in C minor in 1786/85 and premiered it at the Burgtheater n Vienna in April 1786. It uses an imposing orchestra (flute, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, horn, two trumpets, timpani and strings), and is the only piano concerto scored for both oboes and clarinets, and only one of two in a minor key. The concerto was written for Mozart to play at one of his own concerts; in all 12 of his concertos were written expressly for himself to play at public concerts. Mozart's concertos in these years are intimately bound up in his projection of himself as a freelance composer, performer and impresario - a role he executed with some success in Vienna at this period. But we have to bear in mind that the music he was writing was, in some way, intended to please and attract the Viennese public, he wasn't writing in a vacuum.

No. 24 opens with an extensive orchestral introduction, dark, dramatic and very symphonic - this would lead to the bigger, dramatic concerts of the 19th century. But when the piano comes in it is all elegance, beauty and poise. What's going on?

Mozart played the concerto on his own Walter piano (at that period the wooden framed pianos were light enough to be carried about). The piano of this period, the Viennese fortepiano, isn't just an early version of the modern concert grand, it is effectively a different instrument. The Viennese pianos were very sensitive to the touch, very responsive; the descent of the key was only half as much as on a modern piano and the force required to depress the key is far less (by as much as a quarter). Playing such a piano required no virtuoso athletics, but needed a finely sensitive touch. Mozart's own Walter survives though Walter modified it nine years after the composer's death so we cannot be certain of details such as whether Mozart raised the dampers during playing with a knee lever or using a hand stop (this latter requiring, of course, the pianist to have a hand free).

Scoring of the accompanying passages inevitably had to be light, with Mozart employing contrast, accent and emphasis instead of the later composer's bravura pyrotechnics. And it is here that we also come to Mozart's relationship to his public, he inevitably was writing the sort of elegant, expressive music which was highly regarded in Vienna at the time.

So a performance with modern forces is inevitably a transcription, re-creating the music writing for one medium in another one. To give one example, the fortepiano just cannot make a large noise so that the livelier passages will sound strenuous even though not loud do our modern ears. On a modern grand, the player must decide whether to opt for a playing style which reflects this in some way. On this disc Alessio Bax plays with a light touch. Accompanied by the Southbank Sinfonia (numbering some 30 players), these are performance which stay within the dynamic parameters of Mozart's original.

Bax's playing is poised, stylish and fluent. Elegance is to the fore, with a fine sense of legato and his passage-work is gloriously even. It is a style which reflects the modern way of playing Mozart's concerti but which does not always mine the darkness in the works. If you listen to John Eliot Gardiner and Malcolm Binns in the first movement of the work (available on YouTube), Binns' playing sounds more strenuous in key passages, it has an element of struggle which reflects the C minor key of the movement. Bax by contrast is fluid perfection and glorious poise. In the busy passages Bax rarely articulates so as to express the tempestuous dark, he keeps beauty and line as clearly most important.

This clearly pays of in the Larghetto second movement. Here Bax's beautiful, singing tone and miraculously legato line do full justice to the movement. The finale is a joyful Allegretto, a series of imaginative variations (eight in all). here Bax is dazzling in his dexterity, with some nicely even passagework. Ironically in many places he exhibits a robustness which is somewhat lacking the first movement. The result is entirely brilliant and admirable, if somewhat sober. Here Bax and Over take quite a serious view of the enjoyment to be derived. I could have wished for something a little perkier and with a little more humour. You feel that Mozart would played it with more of a twinkle in his eye..

I realise that I have effectively taxed Bax with not playing like a fortepiano. That was not my intention, but I feel that any pianist approaching this music must do so in the spirit of creative transcription and look at how to evoke the origin on a radically different instrument.

Piano Concerto no. 27 is Mozart's last concerto, completed in Jan 1791 with Mozart performing the work in March that year - his final concert performance. It is scored for flute, oboes, bassoons, horns and strings. Quite when he wrote is the subject of some discussion, as the paper on which he wrote it dates from 1788. By the time of the premiere, Mozart's appearances in Vienna no longer caused quite such a buzz with the Viennese concert going public as earlier, but the concerto was still very well received. And no wonder, it is a very winning, light-hearted work and entirely lacking in any forebodings of mortality.

The opening Allegro shows Bax playing with great elegance with beautifully shaped phrases, and very expressive. There is a strong contrast between the piano and the orchestra, the two complement each other forming a lovely dialogue. It is a movement which is easy to dismiss as froth, but you can't help feeling that there is a lot going on under the surface. The Larghetto is almost a piano solo with orchestral interruptions. It is undeniably beautiful but perhaps a tad too slow for my taste and played with too much hushed reverence. But Bax clearly feels the music deeply, and his sense of line is very expressive. The final Allegro is a spirited rondo full of sparkling joie de vivre, though not without dramatic moments.

Bax completes the disc with Mozart's solo piano variations on Come un agnello, a tune from Sarti's 1782 opera Fra i due litiganti il terzo gode. Mozart uses Sarti's simple melody as the bass for eight rather delightful variations in which Bax lets rip in the most charming way.

The booklet is to be highly commended as it includes not only an introduction to the pieces by Bax but an extensive essay with musical examples by Patrick Castillo.

Simon Over and the Southbank Sinfonia provide Bax with superb support, by turns virtuoso, dramatic and discreet as the music requires, with some fine solo playing. Luckily these two concertos also give the an opportunity to shine orchestrally as well.

I still have not quite solved my Mozart piano concerto conundrum, but I was highly impressed with Bax's technique and style. Mozart's piano concertos with a talented young soloist accompanied by fine young performer, everyone should give it a try.

Elsewhere on this blog:

- CLoSer - Poulenc and Paris

- Giles Swayne - Stations of the Cross - CD review

- The Sixteen - Choral Pilgrimage

- Poeme d'un Jour -Ailyn Perez - CD review

- Charles Jennens: the man behind Handel's Messiah

- Tenebrae sings Will Todd

- The Firework-maker's Daughter

- Songs of the Sea / Travel - Anthony Michaels-Moore - CD revie

- St John Passion - AAM

- Alice Coote - Die Winterreise - CD review

- A Single Noon - Greg Kallor - CD review

- Tenebrae with Chapelle du Roi

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment