|

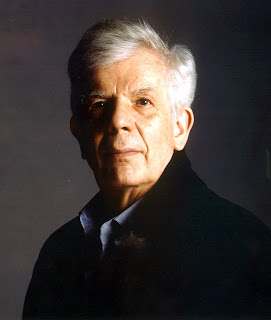

| Christoph von Dohnanyi - photo credit Bertold Fabricius |

Christoph von Dohnanyi was born in Berlin, though because of his father (the jurist Hans von Dohnanyi) they moved around a lot and his schooling included a year at the Thomasschule in Leipzig. There was a lot of music until the start of the war when the music stopped. After the war he was 15 and he had to decide whether to try to make up the years he had missed. At 16 he started studying law in Munich but moved on to music at the Musikhochschule where his studies included composition, chamber music, accompanying and he won the Richard Strauss prize.

'Christoph can you improvise?'

He went to the USA to further his studies, going to Florida where we would study with his grandfather, the composer Ernst von Dohnanyi. When asked about studying with his grandfather he surprised everyone by saying that he had only met his grandfather once previously. He was 20, and his grandfather's first question as 'Christoph can you improvise'. This was something he'd never learned and which he now regards as very, very important. In fact, he commented that his grandfather hated practising and was very good at improvising and he included an anecdote about his grandfather playing an entire sonata in the wrong key.

He spent six years in Lubeck on the music staff of the opera house, coaching , accompanying and such, something which he regards as an essential training for a conductor and points out that Karajan spent nine years in such a role in Ulm. Christoph von Dohnanyi feels that it is important for a conductor to understand voices, and in fact whilst in Lubeck he took voice lessons (he was evidently awful!).

|

| Christoph von Dohnanyi - photo credit Fotostudio Heinrich |

Listening to Mahler secretly with his father.

Whilst studying in Munich Christoph von Dohnanyi had experienced the Musica Viva concerts run by the composer Karl Amadeus Hartmann. These started in 1946, and prior to then there had effectively been no contemporary music in Germany. Christoph von Dohnanyi talked about the amazing feeling after the war, when things opened up and there was a deliberate disconnect from the past. Before then, listening to contemporary music had to be done in secret and he talked of listening to Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde secretly with his father.

The WDR Symphony Orchestra was the first really good orchestra that Christoph von Dohnanyi worked with. For him, as a conductor the first need is to create a performing instrument. He commented that he wasn't crazy about working on intonation, but it needs to be done. Jonathan Freeman Attwood commented that Christoph von Dohnanyi was famous for his sense of intonation, and he retorted 'Hated for it!'. He went on to add that an orchestra has to be a perfectly tuned instrument, and then you can make music. This extended to doing solo and sectional rehearsals, whilst working with the Vienna Philharmonic on The Ring. When he first worked with the Cleveland Orchestra, they asked him how he wanted the music to sound; he described the orchestra as a wonderful perfect instrument.

He was just discovering Mendelssohn,... he had

not heard any Mendelssohn for 12 years

In London he conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra, a relationship which he described as 'a real partnership'. He continued, adding that though 'democracy has its problems' the way of working we have in the UK is very special. The conductor and the orchestra each have to recognise authority in the other, and there is real cooperation; something which he does not find in USA and Germany.

We heard part of the finale of Mendelssohn's Fourth Symphony which Christoph von Dohnanyi made with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Christoph von Dohnanyi said that when he was making the recordings he was just discovering Mendelssohn, pointing out that he had not heard any Mendelssohn for 12 years ('when these criminals were in charge of our country'). He also added that he did all the Mendelssohn symphonies and he suddenly became a Mendelssohn specialist which is dangerous for a conductor. He said that he would not perform the Mendelssohn like that now, and thought that it was dangerous that people could listen to recordings made 20 or 25 years ago and thing that that was the way to do it.

|

| Christoph von Dohnanyi |

Listening to an extract from Christoph von Dohnanyi's recording of Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben led to a discussion of that composer's music. When performing it, for Christoph von Dohnanyi less is more; he feels that it is tempting for us to over emphasise and exaggerate the more sentimental elements. Mahler he described as something totally different, and that there are very few symphonies in the classic sense written after Mahler. For him, it is the reading between the lines which is the main thing.

You can play Bach on the saxophone

89% of the concerts which Richard Strauss conducted included some Beethoven. For Christoph von Dohnanyi it is the even numbered symphonies which are most difficult and you should not do number 6 before you are a certain age. He went on to comment that Beethoven was a strongly involved political personality, in many things as a human being he was wrong, but above all this is the genius of the music.

Regarding Bach, he commented that he does not dare to perform the composer's music in countries where there is only one way of performing Bach. He performed the Matthew Passion in Cleveland with a full orchestra, for Christoph von Dohnanyi there are many ways of addressing it: you can play Bach on the saxophone! But Christoph von Dohnanyi admitted that he had learned a lot from the people who tried to take performance practice back to Bach's period and to use old instruments. Initially he had not been convinced, but realised that it gave a freedom from what he called the tyranny of 19th century interpretation.

He called Schoenberg the most important figure for the development of music in the 20th century.

'Education is what is left when you have forgotten everything else'

In rounding off the discussion Jonathan Freeman Attwood asked him if he had any advice for an aspiring young conductor. His initial response was 'Have good health insurance', before going on to say that the beginning is hard and you should go to the smallest city you can find and learn conducting out of the spotlight. He finished by quoting Schopenhauer - 'Education is what is left when you have forgotten everything else'.

After a break, the proceeding continued with a round table between Christoph von Dohnanyi, Tom Service, Nicholas Payne and Peter Katona (who had worked as Christoph von Dohnanyi's assistant) on Christoph von Dohnanyi's operatic career.

Elsewhere on this blog:

- Ravishing: Carolyn Sampson and the Heath Quartet in Schoenberg & John Musto - concert review

- Vividly theatrical: Rossini's La gazza ladra - CD review

- Musicology and Musicianship: Handel's L'Allegro - CD review

- Imaginative translation: Samson et Dalila at Grange Park - opera review

- Satisfying balance: La Bohème at Grange Park - opera review

- Virtuosity with a human touch: My encounter with Matthew Sharp, cellist, baritone, director, creative director of Revelation St Mary's, artist in association with the English Symphony Orchestra - interview

- Brilliant personal vision: Le Concert Spirituel in Vivaldi and Campra - concert review

- Strong musical performance: Opera Holland Park's first Aida - opera review

- Into the 20th century: Mahan Esfahani - CD review

- Vibrant conclusion: The Cardinall's Musick in Robert Fayrfax - concert review

- Look no microphones: Fiddler on the Roof with Bryn Terfel - opera review

- Mesmerising: Mark Padmore & Roger Vignoles in Britten & Schubert - concert review

- Home

.webp)

%20and%20kids.jpg)

.jpg)

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete