|

| Christian Gerhaher with his Wigmore Medal at the Wigmore Hall 12.10.16 - photo Simon Jay Price |

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on Oct 12 2016

Star rating:

One of the great lieder singers of our day in an intense and interior programme

Recitals by the German baritone Christian Gerhaher are rather special affairs and his concert at the Wigmore Hall on Wednesday 12 October 2016, with his regular accompanist Gerold Huber, was no different. It was a very serious affair, Antonin Dvorak's Biblical Songs op.99, some late Schumann (his Six Poems of Nikolaus Lenau and Requiem Op.90 and Three Song Op.83) finishing with Schumann's Twelve Kerner Lieder Op.35, a song-sequence from the great year of 1840 but one which is slightly less easily accessible than its fellows. But it was a programme which provided enormous rewards if you were prepared to surrender to Gerhaher's very personal and very intent delivery. Every note and every word counted, creating a mesmerising sequence of sung poetry which, at first under-stated, developed a cumulative power.

Dvorak's Biblical Songs date from the same American period of the Symphony No. 9 and String Quartet No. 12 "American", but the songs lack the sheer melodic approachability of these works. Instead, the austere directness of Dvorak's setting of the Czech translations of the psalms has a contemplative and troubled feeling which perhaps reflects his own unease in the USA far from loved ones (his close friend Hans von Bülow died whilst he was away and his father was terminally ill). The songs virtually have to be sung in Czech,, Dvorak's publisher Simrock was annoyed that the pieces did not work in German.

Whilst Gerhaher used a music stand for the whole concert, in the Schumann songs he barely glanced at the music. However for the Dvorak we were very aware that he was using the music extensively, though his sheer communicativeness meant that this was not a performance where the performer's head was buried. But there was a certain constraint about the songs, as if they had not been quite run in, or perhaps this was the way Gerhaher wanted to project them.

He sang quite directly, trenchant lyalmost, but with a strong sense of inwardness and intimacy. Overall his performance was rather contained, yet there was still an element of Old Testament prophet about him, perhaps like Moses on a good day in confiding mode. Some of the songs had a folk-like lyricism to them; for all the austerity and directness of Dvorak's setting, Gerhaher brought a fine sense of detail to the phrasing; the songs were very word based, lyrical and free arioso being the dominant mode.

Gerhaher is a very visual singer, if you don't look at him you miss a great deal as he complements his vocal colouration and phrasing with a strongly projected image, which meant ignoring the English translation of the Czech and not following it. Perhaps there are occasions when surtitles in recitals are desirable.

|

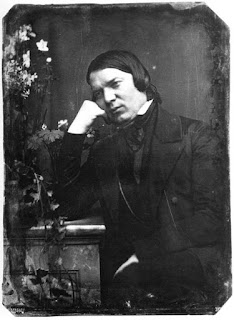

| Robert Schumann in an 1850 daguerreotype |

Huber's piano contributed too so that this was a real partnership. There was a lovely introduction to 'Meine Rose', with a beautiful subtlety to the way Gerhaher's vocal line slipped in as a continuation of the piano. 'Kommen und Scheiden' was remarkably conversational, with some lovely turns of phrase, whilst 'Die Sennin' started as delightfully carefree before developing some interesting expressive possibilities. 'Einsamkeit' was quiet, intimate and bleak, and 'Der schwere abend' continued the mood with dark piano and veiled voice. The poet Lenau had ended up in a mental asylum, something which gives the cycle added poignancy knowing that Schumann himself would be in one four years later. When Schumann wrote the cycle he was under the impression Lenau was dead and so added the final 'Requiem'. With its flowing piano and more lyrical vocal line, this song could seem more straightforward but Gerhaher and Huber developed it into something remarkable with the first real climaxes of the cycle .

After the interval we heard the Three Songs, Op. 83 also from 1850, these too had a very inward, interior quality. 'Resignation' was very much like an interior dialogue, with Huber's piano wonderfully understated. Gerhaher made the lyrical 'Die Blume der Ergebung' very conversational, this was really about the words, and the final song 'Der Einsiedler'was rather stark and sombre, sung in veiled tone with an ending that was other-worldly.

Finally we heard the Twelve Kerner Lieder Op.35 which date from the same year as Dichterliebe, Myrten, and Frauenliebe und -leben. The songs lack the immediacy and sheer melodic beauty of some of Schumann's other songs from the period, and instead there is an intensity and deepness to the cycle which makes it really worth exploring. Gerhaher took a relatively understated approach, again emphasising the intense, interior nature of many of the songs and even making some of the more demonstrative ones rather less so than usual. This, combined with his attention to the text, gave the cycle a great sense of cumulative power.

We opened, however, with a demonstrative flourish with a vivid account of 'Lust der Sturmnacht', but 'Stirb, Lieb' und Freud'! was thoughtfully considered, making this strange song into something quietly intense with beautiful placement of the text. There was a swagger to 'Wanderlied' but this was serious joy, and 'Erstes Grün' was rather touching. In 'Sehnsucht nach der Waldgegend' we were aware of something deeply complex beneath the lyrical beauty, and 'Auf das Trinkglas eines vertorbenen Freundes' was certainly no obvious drinking song, becoming mysterious and not a little disturbing.

'Wanderung' was lively but controlled until the vivid final stanza, 'Stille Liebe' was again interior and thoughtful crowned by a lovely piano postlude. The mood continued with the rather questioning 'Frage'. 'Stille Tränen' made a real heart of the sequence, with Gerhaher giving weight to the long unfolding line, performed with intensity and something akin to bitterness. The final two songs 'We machte dich so krank?' and 'Alte Laute' were quietly conversational and held in, the one almost a continuation of the other until the magical final line.

Gerhaher and Huber's performance made sense of the Kerner Lieder as a sort of emotional journey, with a sense of the young man's exterior travel mirroring a more complex and darker interior journey. It was a very personal and very moving account of this unaccountably underperformed cycle.

The capacity audience was rightly enthusiastic and we were treated to an encore, 'Mein schöner Stern' from Schumann's Minnespiel.

Afterwards Christian Gerhaher was presented with the Wigmore Medal by the hall's patron HRH The Duke of Kent. In his introduction John Gilhooly, the hall's director, talked about how following his Wigmore Hall debut 16 years ago, Christian Gerhaher had demonstrated his belief both in the Wigmore Hall and in the song recital. In his speech of thanks Christian Gerhaher commented that if the medal wasn't so beautiful, he wished he had a saw to put it into two parts so it could be shared with Gerard Huber. He also commented that he was happy there wasn't a hall or institution quite like the Wigmore Hall in his native Munich, as if there was he would not come to the Wigmore Hall so often.

Christian Gerhaher and Gerold Huber are repeating the recital on Friday 14 October 2016 in the Sheldonian Theatre as the opening recital of this year's Oxford Lieder Festival.

Elsewhere on this blog:

- Cross-cultural friendship: Jean-Guihen Queyras Thrace: Sunday Morning Sessions - CD review

- Delightful evening with a dark backdrop Handel's Xerxes from ETO - Opera review

- Liszt for the 20th century: Kenneth Hamilton plays Ronald Stevenson - CD review

- Interest and disappointment: Holst Singers in RVW - concert review

- Songs of the big smoke: Song in the City's Voices of London - Cd review

- A feast of pianism: Two-piano gala at the London Piano Festival - concert review

- Semiramide, la signora regale: Anna Bonitatibus at the Wigmore Hall - concert review

- A Voice from Heaven: The King's Consort's highly recommended new disc - CD review

- Experimental textures: Miles Cooper Seaton and Distractfold at Kammer Klang - concert review

- Characterful & moving: Tavener's late Missa Wellensis - CD review

- Stylish and compact: Ann Murray in Dido and Aeneas - concert review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment