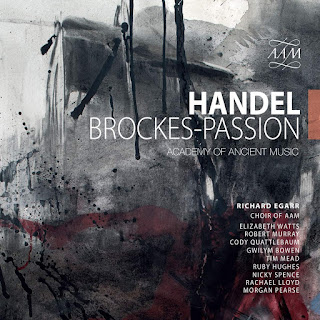

George Frideric Handel Brockes Passion; Elizabeth Watts, Robert Murray, Cody Quattlebaum, Ruby Hughes, Rachael Lloyd, Tim Mead, Nicky Spence, Gwilym Bowen, Morgan Pearse, Academy of Ancient Music, Richard Egarr; AAM

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on 14 October 2019 Star rating: (★★★★★)

A striking combination of scholarship and performance, the Academy of Ancient Music's new recording of Handel's Brockes Passion complements a fine performance with elucidation of the work and the new edition

With period performance, scholarship has always gone hand in hand with singing and playing, performers often researching works and performance styles as part of the process of creating a particular performance. This is often noticeable on recordings which can be the vehicle for presenting new ideas and findings. John Butt and the Dunedin Consort, for instance, have produced a series of recordings of major works by Handel and by JS Bach which explore performance practices in the works, and the Dunedin Consort's recording of Bach's St Matthew Passion includes the possibility of downloading the sermon which came between parts one and parts two, thus giving the listener the opportunity to re-create as close as we can the experience of listening to the work in the Good Friday service in Leipzig.

Richard Egarr and the Academy of Ancient Music's new recording of Handel's Brockes Passion, on its own label, takes this to a rather new level, as the recording [based on performances in 2019, see my review] unveils a significant new edition of the work (created especially for the recording) and the CD set includes an impressive book which explores the new research in fascinating detail. The recording itself is similarly comprehensive, with the complete Brockes Passion in German over two CDs along with a third CD containing alternative versions of four items, and a recording Charles Jennens' unfinished English version of the work.

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on 14 October 2019 Star rating: (★★★★★)

A striking combination of scholarship and performance, the Academy of Ancient Music's new recording of Handel's Brockes Passion complements a fine performance with elucidation of the work and the new edition

With period performance, scholarship has always gone hand in hand with singing and playing, performers often researching works and performance styles as part of the process of creating a particular performance. This is often noticeable on recordings which can be the vehicle for presenting new ideas and findings. John Butt and the Dunedin Consort, for instance, have produced a series of recordings of major works by Handel and by JS Bach which explore performance practices in the works, and the Dunedin Consort's recording of Bach's St Matthew Passion includes the possibility of downloading the sermon which came between parts one and parts two, thus giving the listener the opportunity to re-create as close as we can the experience of listening to the work in the Good Friday service in Leipzig.

Richard Egarr and the Academy of Ancient Music's new recording of Handel's Brockes Passion, on its own label, takes this to a rather new level, as the recording [based on performances in 2019, see my review] unveils a significant new edition of the work (created especially for the recording) and the CD set includes an impressive book which explores the new research in fascinating detail. The recording itself is similarly comprehensive, with the complete Brockes Passion in German over two CDs along with a third CD containing alternative versions of four items, and a recording Charles Jennens' unfinished English version of the work.

The recording features an impressive line of up soloists directed by Richard Egarr, Robert Murray (Evangelist), Cody Quattlebaum (Jesus), Elizabeth Watts (Daughter of Zion), Ruby Hughes (Faithful Soul), Rachael Lloyd, Tim Mead (Judas), Gwilym Bowen (Peter), Nicky Spence (Faithful Soul) and Morgan Pearse, along with the Choir of Academy of Ancient Music.

Handel wrote his setting of the passion by Barthold Heinrich Brockes in 1716 and it was performed in Hamburg in 1719, under the direction of Handel's friend and erstwhile colleague at Hamburg Opera, Johannes Matheson. It proved popular and would have a number of performances in Hamburg, but Handel never kept a copy of the autograph manuscript (this has disappeared) and never performed the work in London. Almost certainly, he sent the manuscript to Matheson and he understood that a performance of the work in England was not possible.

In fact, he included music from a number of London and Italian period works in the piece and in turn would mine the Brockes Passion for music for his early oratorios. The surviving manuscripts of the work include one which was partially copied by J.S.Bach and this version was performed in Leipzig under Bach's direction, Handel's setting seems to have influenced Bach's St John Passion.

So why did Handel write the passion? We can never know for certain, but the uncertainty in England surrounding the 1715 Jacobite uprising and the Old Pretender's attempt to gain the throne must have given Handel cause for concern. His fortunes were firmly linked to the Hanoverian dynasty, and the Brockes Passion may have been something of an insurance policy, a work which would stand him in good stead if he had to return to Germany for work.

Duarte's new edition makes significant changes to the version of the work known (via the last critical edition in the mid-1960s) including adding 63 extra bars! New scholarship has enabled us to revise opinions of the relative merits of the various manuscripts, and Duarte has taken advantage of this. The Academy of Ancient Music used quite a large ensemble for the piece, and the accompanying book includes a fascinating article about the logistical differences between the Hamburg performances and the sort of ensembles Handel was writing for in London at the period, and the one-to-a-part type ethos of Bach in Leipzig. So we have five oboes (lovely) and three bassoons in addition to a significant body of strings (17) and a choir of 20.

The work is the genre known as a Passion Oratorio, and was designed explicitly for concert use whereas Bach's Passions were designed for church use. The difference is that Bach's Passions use the Biblical narrative for the recitative with added arias whereas Brockes' text resets the entire story in his own, very clotted and emotional, verse. There is still an Evangelist (Robert Murray) and Jesus (Cody Quattlebaum), plus sundry disciples, Peter (Gwilym Bowen), Judas (Tim Mead), James (Cathy Bell) and John (Kate Symonds-Joy), who enact out the passion in direct dialogue and arias. But the largest single role (with a whopping 14 arias plus duets) is the Daughter of Zion (Elizabeth Watts), with another large role being the Faithful Soul (Ruby Hughes, with certain arias given to Nicky Spence and Morgan Pearse).

This results in quite a strange piece, the role of the Daughter of Zion and the Faithful Soul is to comment, to apply the story to our situation and to express feelings about the Crucifixion narrative. It is from these arias that Bach selected his Brockes settings which he used for the arias in his own Passions, but Bach's balance between aria comment and Biblical narrative is completely different to Brockes's own (rather surprisingly Handel set Brockes text in full, without making any changes). In part two, the solo roles drop away and even Jesus falls silent (his last words being delivered as reported speech by the Evangelist!), and instead we have a long meditation from the Daughter of Zion and the Faithful Souls. It turns the work from one of pure narrative into being about our reaction to it, Brockes spends a lot of time telling us what we should be feeling.

What is noticeable about the piece is the way that in the recitatives Handel indulges in a lot of word painting but in setting Brockes highly emotionally wrought aria texts, Handel creates something more balanced and distanced, might one even say a bit more generic. As if he was not entirely comfortable with the impassioned genre of the piece.

There are times when you look at the libretto and think, oh not another aria for The Daughter of Zion, despite Elizabeth Watts' considerable talents. She makes a strong case for the piece, even though she spends a lot of time lamenting. Her two final arias in Part One are wonderful, and both pair her with Leo Duarte's solo oboe to powerful and consoling effect. And then in Part Two she has a striking duet with Jesus, one of a number of places where the Daughter of Zion's rhetorical questioning inserts itself into the narrative, so she also has a powerfully dramatic arioso when Jesus refuses to answer Caiaphas (Morgan Pearse) and another aria begging Pilate (Morgan Pearse again) not to give up. And it is the Daughter of Zion who has the last aria, a striking piece with long passages for voice and oboe with no orchestral support.

Ruby Hughes is barely used in Part One, but in Part Two her Faithful Soul starts reacting to the narrative, with Hughes giving a performance which powerfully identifies with the character's reactions. Her arias are often lyrical (in contrast to the powerful language), and I was particularly struck by 'Den Himmel gleicht' with its huge solo violin part (Bojan Cicic), though sometimes arias are reduced to just Hughes' plangent voice and continuo. Her final contribution is a striking accompagnato where the music really did react to the drama of the words.

Murray brings a strong dramatic sense to to the role, and his performance is compelling. Rather more demonstrative than he might be in Bach, but in the context of this work it works. Cody Quattlebaum's account of Jesus' music was finely lyrical and inward account, making a very human Jesus (though his contributions to Part Two are reduced to a minimum).

Tim Mead makes a strong Judas (evidently having the role performed by an alto was traditional). His final contribution is a pair of dramatic recitatives with a vigorous aria full of jagged rhythms in the middle which make a powerful conclusion to Part One. Gwilym Bowen's Peter gets a lot of the dramatic action in Part One, with Bowen creating a very human character and it was in moments like this that we experience Handel the dramatist.

Nicky Spence brings great rhetorical strength to his role as the Faithful Soul, particularly in his first aria where he seemed to be directly challenging the listeners. Spence's performance is particularly impressive being as earlier on in the week before the performance at the Barbican he sang the title role in excerpts from Wagner's Parsifal with the Halle and Sir Mark Elder at York Minster, and it did strike me that someone ought to snap him up quick to play Handel's Samson or Jephtha.

Morgan Pearse gives a series of strong character sketches as Caiaphas, Pilate and the Centurion. Rachael Lloyd is rather underused but has a strong moment as Mary with a dramatic recitative and a touching duet with Quattlebaum's Jesus.

Contrary to Handel's English oratorios, here his writing for the chorus is relatively brisk, and even the Chorales are simply neatly efficient, with vigorous choral writing for the crowds. but there are no large scale choruses of a style we might be familiar with either from Bach's passions or Handel's oratorios.

Listening to the work is a strange and unsettling experience. On the one hand you have Handel in German (a language he rarely set once he left Hamburg), and a major work with which you are unfamiliar. Then there is Brockes' libretto, where I find his treatment of the passion with the extensive comment and instruction about what we should feel, to be entirely unsympathetic. I will be quite frank and admit that if the work was not by Handel, I would not be giving it anything like the attention. And then there is the fact that Handel, because he knew the work was not going to be performed in England, re-used vast quantities of it, so that it is familiar in other situations!

It is important that performances like this one be given uncut, so that we can experience the work in full but I imagine that if the work is to become a more regular visitor to the concert hall then it will need trimming and re-shaping.

The book which accompanies this performance includes 10 articles by Richard Egarr, Leo Duarte, Alexander Van Ingen, Dr Ruth Smith, Seren Charrington-Hollins, Prof. Joachim Whaley, Dr Bettina Varwig, Jane GLover and Joseph Crouch, providing full information about Leo Duarte's new edition as well as the full background to the work and the performances. There are even helpful lists of performances of musical settings of Brockes' Passion Text (1711-1750), recordings and broadcasts of the Handel's setting, and recordings of other composers' settings. Plus of course, the complete libretto.

The scholarship, performances and recording could not have taken place without the considerable crowd-funding, and the book documents this.

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) - Brockes Passion

Daughter of Sion - Elizabeth Watts

Evangelist - Robert Murray

Jesus - Cody Quattlebaum

Peter - Gwilym Bowen

Judas - Tim Mead

Faithful Souls - Ruby Hughes, Rachael Lloyd, Nicky Spence, Morgan Pearse

Mary - Rachael Lloyd

Pilate, Centurion - Morgan Pearse

James - Cathy Bell

John - Kate Symonds-Joy

A Soldier - Rachael Lloyd

Caiaphas - Morgan Pearse

Maids - Ruby Hughes, Rachael Lloyd, Philippa Hyde

Chorus and Orchestra of the Academy of Ancient Music

Director & Harpsichord - Richard Egarr

Continuo - Sarah McMahon (cello), Richard Egarr (harpsichord), Alex McCartney (theorbo), Julian Perkins (organ)

Recorded 11, 17, 18 April (Henry Wood Hall), 19 April (Barbican Hall)

AAM AAM0017 3CDs [75.42, 73.10, 25.13]

Elsewhere on this blog

- A barren emotional landscape barely disguised by the production’s kitsch fairy-tale opulence: Turandot, Met Live in HD (★★½) - opera review

- Bringing a rarity alive: Verdi's Un giorno di regno from Chelsea Opera Group (★★★★) - opera review

- Voices in the Wilderness: cellist Raphael Wallfisch on his series of cello concertos by exiled Jewish composers - interview

- The Song of Love: songs & duets by Vaughan Williams from Kitty Whately, Roderick Williams, William Vann (★★★★) - CD review

- Will put a smile on your face: Vivaldi's L'estro armonico in new versions from Armoniosa (★★★) - CD review

- 17th century Playlist: from toe-tapping to plangently melancholy, Ed Lyon & Theatre of the Ayre (★★★★★) - CD review

- Magic realism, politics and terrific songs: Weill and Kaiser's Winter's Fairy Tale in an imaginative production from English Touring Opera - opera review

- Orpheus goes to Hell: Emma Rice's lively new production somewhat misses the point of Offenbach (★★★) - opera review

- Thought provoking and engaging: Mozart's The Seraglio at English Touring Opera (★★★★) - opera review

- Not letting the audience off the hook: I talk to Simon Wallfisch & Edward Rushton about performing Lieder, & about their new album - interview

- Listening with new ears: Masaaki Suzuki conducts Mendelssohn's Elijah with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (★★★★½) - concert review

- Guy Cassier's Ring Cycle production revived at Berlin Staatsoper (★★★★★) - Opera Review

- Love and potions on Barry Island: Donizetti's The Elixir of Love at the King's Head Theatre (★★★½) - opera review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment