|

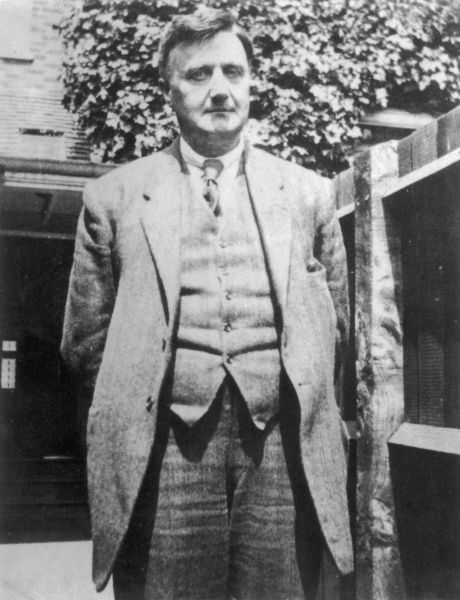

| Vaughan Williams in the 1930s |

Reviewed 29 May 2022 by Tony Cooper

The Norfolk & Norwich Festival not only celebrated its 250th anniversary this year but also marked the 150th anniversary of Ralph Vaughan Williams, so closely involved with the festival in the 1930s, with a rare performance of his Five Tudor Portraits.

It was celebration time throughout this year’s Norfolk & Norwich Festival on its 250th anniversary but the final concert marking Ralph Vaughan Williams’ 150th anniversary featuring a performance of the composer’s Five Tudor Portraits by the Norwich Philharmonic Chorus and Britten Sinfonia, conducted by William Vann with soloists Rebecca Afonwy-Jones and Dominic Sedgwick, put the icing on the cake. The performance was truly favoured by the packed house in St Andrew’s Hall, ‘home’ to the festival since its founding as a Triennial event in 1824.

However, the festival’s roots can be traced back to the late 18th century when in 1772 (listed as such in the Oxford Dictionary of Music) a series of concerts were held on an ad hoc basis in St Andrew’s Hall while an annual performance of an oratorio took place in Norwich Cathedral.

Pairing the Britten Sinfonia with the Norwich Philharmonic Chorus, so well drilled by David Dunnett, Norwich Cathedral’s organist, proved a good call as they delivered a masterful reading of Five Tudor Portraits set to a text by Tudor poet, John Skelton, known as a ‘Skeltonic line’, embodying a short erratic rhyming verse probably descending from medieval Latin rhyming prose.

By the way, Skelton, tutor to Prince Henry, afterwards King Henry VIII, was a ‘local’ born around 1460 probably in Diss in the last decade of the 15th century. He was appointed Rector of St Mary the Virgin in this important south Norfolk town in 1504 preaching the gospel here until his death in 1529. Highly regarded by Caxton he found great favour with Erasmus, too, but critical reception places him firmly in the ‘rougher foothills’ of English poetry. But I’m not so sure about that. His text for Five Tudor Portraits certainly found favour with me.

But despite the initial success of the work, it has not subsequently enjoyed the frequency of performance as it probably should have although the Norwich Philharmonic Society put on a good show of the work in December 2008. Hopefully, this performance by the festival will somehow engineer a few others round the country. The reason for lack of performances may well lie in its difficulty especially in respect of the characterisation required and, indeed, the earthiness of the archaic humour contained in many of the verses such as the racy text found in the first movement 'The Tunning of Elinor Rumming'. Nowadays, though, tame stuff!

Perhaps the English-born music critic and author, Michael Kennedy, has the answer. He states in his excellent book, The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams (which, thankfully, has been on my shelves for years) that the design of Five Tudor Portraits may be to blame as there are three excellent short movements outweighed by two long ones of which 'Jane Scroop' is so good that it tends to overshadow the rest.

It seems that Vaughan Williams was familiar with John Skelton’s poetry from an early age and, indeed, was strongly influenced by Tudor music. His wide output over practically a 60-year period marked a decisive break in British music from its German-dominated style of the 19th century. This is primarily down to the fact that he studied for a year in the early 20th century with the renowned French composer, Maurice Ravel, who helped him clarify the textures of his music and free it from Teutonic influences.

As a curtain-raiser to the evening, Mozart’s Divertimento in D major, K.136 - seemingly as popular now as in Mozart’s day and written in 1772 thereby fitting in nicely with the festival’s illustrious history - proved a good choice but, I think, it would have been more appropriate to have had an 'opener', say, by Edward Elgar or, indeed, by Arnold Bax or EJ Moeran, composers all closely associated with the 'Triennial' at the time of Vaughan Williams.

Furthermore, one could have gone for Benjamin Britten's Our Hunting Fathers - another rarely performed work and, indeed, another Triennial commission which, incidentally, received its première at the same concert as Five Tudor Portraits. Anyhow, that’s how it turned out and the Divertimento found the esteemed players of the Britten Sinfonia alert to the 'wunderkind' of Salzburg’s writing with Clio Gould leading the players in a fine and exemplary performance.

Vaughan Williams was on the bill for the second work, though, with Norfolk Rhapsody No.1 in E minor. Out of the three orchestral 'Rhapsodies' he wrote, the 'first', written in 1906, was the only one to survive in its entirety as the 'second' existed only in a fragmentary form while the score for the 'third' was, unfortunately, lost. The 'first', however, received its première in London on 23 August 1906 conducted by Henry Wood and was later substantially revised for a performance in Bournemouth in May 1914.

All the 'Rhapsodies' (originally intended to form a kind of 'folk-song symphony') were written between 1905-06 and based on folksongs collected by Vaughan Williams in Norfolk mainly from King’s Lynn North End, home to most of the port’s fishing community. Here Vaughan Williams rubbed shoulders with old seafarers such as Joe Anderson and James 'Duggie' Carter spinning yarns and belting out songs like 'The Captain's Apprentice', 'Dogger Bank' and 'The Mermaid' in the Retreat, formerly the Tilden Smith, so named after a boat which regularly called in at Lynn in the 1860s. It was the last surviving fisherman’s pub (now converted into housing) in Pilot Street, coined the 'High Street' of North End.

A glowing and entertaining piece, Norfolk Rhapsody No.1 began with a lovely introduction based on two well-loved sailors’ songs, 'The Captain’s Apprentice' and 'The Bold Young Sailor' and continued with a sprightly trio of songs 'A Basket of Eggs', 'On Board a Ninety-eight' and 'Ward, the Pirate’ capturing the spirit and imagination of old windswept Norfolk seafarers and, indeed, the 'golden' era of the Triennial festivals.

Under the baton of William Vann, director of the London English Song Festival, the Norwich Philharmonic Chorus excelled themselves in Five Tudor Portraits. After all, works such as this is the Phil’s bread and butter! They know the 'old'choral repertoire well and it showed through and through in a glowing, bountiful and exciting performance.

Commissioned by the Norfolk & Norwich Triennial Festival of 1936, the first performance of Five Tudor Portraits (there was nearly a 'sixth'focusing on Margery Wentworth but abandoned by the composer) was heard in St Andrew’s Hall, Norwich, with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Festival Chorus conducted by the composer while the soloists featured English-born contralto Astra Desmond and Scottish-born baritone, Roy Henderson.

This performance earned reasonable praise from the audience and critics alike but, nevertheless, a few walked out of the performance including the Countess of Albemarle who found the bawdiness of the lyrics, particularly those appertaining to 'The Tunning of Elinor Rumming'not to her liking. On hearing that she marched out during the performance Vaughan Williams remarked that it 'showed that the choir diction was good'

However, Astra Desmond gave 'the most delicate picture of a drunken hag at the famous brewing' noted The Times 'everyone concerned caught the spirit of the thing and the composer conducted a brilliant performance'. Edwin Evans in The Musical Times reported that he had rarely seen an English audience 'so relieved of the inhibitions of the concert room'. Praise, indeed!

And praise, too, for the soloists on this auspicious occasion. They did the work proud, too, with Welsh-born mezzo-soprano Rebecca Afonwy-Jones and British-born baritone Dominic Sedgwick (a graduate of the prestigious Jette Parker Young Artist Programme, Royal Opera House) joyfully (and effortlessly) singing their respective pieces seemingly without a care in the world. They delivered their parts in a well-read and entertaining performance while Vaughan Williams’ writing cleverly captured the mischief and the rhythm of Skelton’s poetry.

For instance, in the opening bars of 'The Tunning of Elinor Rumming' a bright and merry ballad, Ms Afonwy-Jones richly textured mezzo-soprano voice was so clearly heard in the intimacy of the ecclesiastical surroundings of St Andrew’s Hall, once home to Dominican Blackfriars. And Vaughan Williams' writing of 'Rumming' fitted so well, too, the racy Skelton text with a mixture of rhythms suitably slowed down to accommodate the revelations of 'drunken Alice'punctuated by piccolo, trumpet and horn.

But I think that the 'prize' movement of the whole work fell to Ms Afonwy-Jones with 'Jane Scroop: Her Lament for Philip Sparrow', the fourth (and longest) movement. A thoughtful piece, it tells of Jane Scroop (reportedly a schoolgirl in the Benedictine convent of Carrow Abbey, Norwich) lamenting the loss of her pet sparrow killed by a cat.

Poignancy and tenderness were portrayed equally in both verse and music in such a lovely romantic movement especially in the scene carrying the tiny coffin to its interment with Jane and her friends softly chanting words from the Latin Mass of the Dead. I felt that the orchestral writing in this movement, sensitive to the core, really touched the hearts of the audience and, indeed, members of the chorus, too.

The air, rich in birdsong, witnessed 'Jane’s voice' intoning the Miserere mei, Deus (Have mercy on me, O God), a setting of Psalm 51, while the chorus delicately sang of the approaching night and for the repose of Philip Sparrow’s poor soul. Here Vaughan Williams’ writing is truly inspired, avoiding sentimentality but, nevertheless, evoking an emotional response of genuine depth.

And it was nice to see the men of the Norwich Phil 'out front' in full voice singing the Latin text centred upon John Jayberd, the bigoted and evil-tongued man of Diss in the burlesque-inspired third movement: 'Epitaph on John Jayberd of Diss'. It’s quite possible that Skelton was aware of the eponymous subject of Jayberd and obviously disliked him as he revelled in his demise echoing these sentiments by some brilliant choral writing ending with a parody of the Office for the Dead.

Possessing a nice rounded, articulate, baritone voice, Dominic Sedgwick was heard to good effect in the second and fifth movements entitled 'Pretty Bess', an intermezzo of great charm focusing on the soloist’s protestations echoed by mixed chorus and 'Jolly Rutterkin', a delightful scherzo using cross-rhythms to an exciting degree thereby bringing Five Tudor Portraits to an eminent, satisfying and glorious close.

The last word is saved for William Vann. In a flourish of an energetic passage in Five Tudor Portraits, I should imagine, he broke his baton which diligently landed in the front rows of the stalls. A quick-thinking female member of the audience discreetly picked it up and handed it to Ms Afonwy-Jones on stage but Maestro Vann - who was greatly favoured by the Norwich Philharmonic Chorus - was unfussed by the situation and went on and finished the work by just using his hands.

The audience took over at curtain-call by using their hands, too, in a flurry of thunderous applause while stamping hard the wooden-covered floor and shouting the praises of the performance from the rooftops! It was just like the good old days! Happy sestercentennial! Cake all round!

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A forgotten voice from an earlier era: Mr Onion's Serenade - Mandolin Music of the Edwardian Era - record review

- What a lovely night: an evening inspired by Jenny Lind's charity concerts in Norwich - concert review

- Enjoyment and discovery: Paul McCreesh and Gabrieli Consort & Players in Bach's Ascension Oratorio at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- Adventurous and exciting: So Percussion and Caroline Shaw at the Norfolk & Norwich Festival - concert review

- Time corkscrews inwards: Tom Coult on clocks, time & humanity in Alice Birch & his new opera Violet - interview

- Musical treats: Richard Jones' production of Saint-Saens' Samson et Dalila fails to convince, but there is much to listen to - opera review

- Intensely evocative: Arun Ghosh's spiritual jazz re-imagining of St Francis of Assisi's The Canticle of the Sun premieres in Norwich - concert review

- Striking music, terrific performances: the modern day premiere of Handel's pasticcio Caio Fabbricio based on music by Hasse - opera review

- Rewarding collaboration: Daniel Pioro and Erland Cooper perform live together for the first time at the Norfolk & Norwich Festival - concert review

- The Wreckers returns: Glyndebourne's vividly dramatic new production of Ethel Smyth's opera - opera review

- Blow's Venus & Adonis and Purcell's Dido & Aeneas from HGO - opera review

- Rediscovering the joys of playing together: Noemi Gyori & Gergely Madaras their disc of flute duets - interview

- Magical places: Sam Cave's Refracted Resonance explores contemporary music for classical guitar - record review

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment