Anna Clyne, Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 1, Bartok: Concerto for Orchestra; Benjamin Grosvenor, Philharmonia Orchestra, Joana Carneiro; Royal Festival Hall

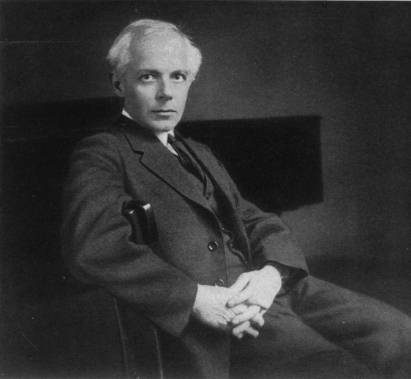

Bela Bartok in 1927

Reviewed 1 December 2022 (★★★★½)

An evening of contrasting showpieces, held together by some superb music making and a striking sense of balance between control and freedom.

It has been something of a Bartok week, here on Planet Hugill. On Sunday we heard the Barbican Quartet performing Bartok's String Quartet No. 4 at Conway Hall [see my review] and at the pre-concert talk, I spoke about Bartok's six mature string quartets. Then last night (Thursday 1 December 2022), Joana Carneiro and the Philharmonia performed Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall as part of a concert that included Anna Clyne's This Midnight Hour and Chopin's Piano Concerto No. 1 with soloist Benjamin Grosvenor.

Portuguese conductor Joana Carneiro, who was principal conductor of the Orquestra Sinfonica Portuguesa at Teatro Sao Carlos in Lisbon from 2014 until January 2022, has appeared with ENO and Scottish Opera, as well as guest conducting a number of UK orchestras. Her performance of this programme in Bedford was her debut with the Philharmonia.

The programme opened with Anna Clyne's This Midnight Hour. Clyne is currently the Philharmonia's featured composer and Clyne's 2015 piece, written for Orchestre national d'Île-de-France, was inspired by a pair of contrasting poems by Juan Ramon Jimenez and Charles Beaudelaire, which enabled Clyne to create a piece of highly contrasting section. Perhaps we should accept it as one of those pieces where we worry less about the why, the inspiration and simply sit back and enjoy. Carneiro drew wonderfully vivid playing from the orchestra in the vigorously energetic opening section, rhythms tight and full of impetus. Carneiro's style is not splashy, throughout the evening I was impressed by the way she drew vivid playing from the orchestra that was highly disciplined yet engaging and often thrilling. The central section, where we seem to move into a Parisian cafe, provided a striking contrast in atmosphere.

Chopin wrote a pair of piano concertos in 1829/30, shortly before he left his native Warsaw for Paris as a result of political events in Poland. His Piano Concerto No. 1 was in fact the second to be written (and premiered in Warsaw in 1830) but the first to be published. We have to bear in mind the early date, this was fifteen years before Schumann wrote his piano concerto, Mendelssohn would write his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1831, and Liszt worked on his first piano concerto from 1830 to 1848. Beethoven wasn't long dead, and each composer was working through ideas about the relationship of soloist and orchestra, what the concerto was for.

Chopin's focus is securely on the piano; his preferred style of expression was the intimate recital in the salon, rather than the big barnstorming favoured by Liszt. The orchestra provides the support and structural context for the pianist. In the first piano concerto, the long, and striking orchestral peroration presents the work's main themes which are then explored and decorated by the soloist. Chopin largely avoids stressful development, favouring a more decorative approach. Inevitably, playing in the Royal Festival Hall with a large orchestra and a modern grand, Grosvenor, Carneiro and the orchestra pushed the concerto rather closer to Liszt than perhaps would have been the case at its premiere in Warsaw (consider a hall seating perhaps 500, a small-ish orchestra with gut strings and narrow-bore brass, plus an early 19th century piano).

What was striking about the opening was the way Carneiro made her large orchestra so graceful and light on its feet, and the dance element in the music really came out. Grosvenor's approach to the music was highly serious and rather classical. The focus, nearly always, was on his right hand, and the way he could shape elaborate arabesques, to draw out a line whilst throwing in all the amazing decoration. There were big dramatic moments and cascades of notes, but Grosvenor always drew back, drawing us in. Yet there was a strength in his playing too, helped by the fundamental rhythmic nature of the left hand; extreme volatility underpinned by a strong bass. The second movement started with some lovely transparent orchestral playing, but quickly we moved to the lovely simplicity of the piano solo. Grosvenor allowed the music to speak here, shaping it but not going overboard, with the orchestral players simply providing touches of colour. The transition was mesmerising, leading to the wonderful final section where the orchestra took over the melody and Grosvenor gave us pure decoration. The interaction between orchestra and soloist in the final movement was delightfully skittish, the strong, sober orchestral statements contrasting with Grosvenor's capricious piano solos. Even the second theme, played with lovely delicacy by Grosvenor, had a delightfully skittish edge.

Bartok tended to avoid the classic orchestral symphonic; yes, he wrote concertos, but when writing for orchestral alone he inclined towards the suite and of course his remarkably symphonic writing in his ballets. His approach to structure was always idiosyncratic, just look at his six major quartets that use the Austro-German string quartet form, yet within this, the structure was all Bartok's own. So, writing a purely orchestral work in the USA in the 1940s, ill, depressed, short of money and lacking adequate American support for his compositional career, Bartok's regeneration with the Concerto for Orchestra is remarkable.

The first movement began in haunting, night-music style but the strong cello line rolled onwards and gathered energy inexorably, leading to the energy of the main section. The first real tutti had a remarkable intensity, but Carneiro moved easily from powerful gestures to the light and transparent, bringing a combination of discipline and restlessness to the music, always unsettled. The violence in this movement was sharply etched, offset by lovely quieter moments. Two perky bassoons began the delightful game of couples in the second movement. There was wit here, but with a sharp edge, everything precise and controlled yet not overdone. I loved the sharpness of the rhythms and orchestral gestures, yet Carneiro gave the musicians freedom as well. The elegy began in a controlled, intense fashion, with woodwind phrases floating over the strings. The orchestral outbursts, with the cascades of notes, were overwhelming, the screw tightened yet the moments of energy could easily evaporate. The fourth movement began with a strong gesture, then lovely, shapely woodwind phrases. Carneiro was not content to simply sit back, every phrase was beautifully shaped yet never felt overdone. The silly tune in the middle with its raspberries (possibly Lehar, probably a sarcastic reference to Shostakovich) was an engaging interlude before the excitement of the final section developed. The final movement began in an exciting, yet tightly controlled fashion, with the suppressed excitement finally overflowing. There was a sense of ideas spilling over each other, and Bartok fills the movement to overflowing with thematic ideas so that we moved between the excited and moments where everything unwound. Yet, for all her attention to detail and her sense of the moment, Carneiro kept the momentum and impetus leading, ultimately, to a vivid and sudden final climax.

Throughout this evening Carneiro drew thrilling playing from the orchestra, with lots of superb individual moments, yet this was all harnessed to a powerful sense of structure and impetus, we never got bogged down.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Wonderfully ambitious: Russell Pascoe's expressive and thoughtful Secular Requiem from Truro Cathedral - record review

- Not so much a history of opera: Simon Banks uses 400 years of opera to hold up a mirror to the attitudes and views of those who watched and commissioned the works - book review

- Barbican Quartet in Haydn, Bartok and Schumann at Conway Hall - concert review

- A hugely ambitious company achievement: Will Todd's Migrations from Welsh National Opera - opera review

- From sets by upcoming British jazz musicians to the outrageously talented finalists of the BBC Young Jazz Musician, a day at the EFG London Jazz Festival - concert review

- I want to live forever: Angeles Blancas Gulin is mesmerising as Emilia Marty in Olivia Fuchs terrific new production of The Makropulos Affair at WNO - opera review

- Finding its true form: Ian Venables' new orchestral version of his Requiem in fine a performance from the choir of Merton College on Delphian - record review

- Celebrating St Cecilia's Day in style: Freiburg Baroque Orchestra in Purcell and Handel at Wigmore Hall - concert review

- Changing Standards: London Sinfonietta at the EFG London Jazz Festival - concert review

- Music for French Kings: Amanda Babington introduces us to the fascinating sound-world of the musette in French Baroque music - cd review

- 2117/Hedd Wyn: Stephen McNeff & Gruff Rhys' Welsh language opera celebrating the Welsh poet - record review

- The sad clown and the ingenue: Jo Davies' 1950s-set production of The Yeomen of the Guard from English National Opera - opera review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment