|

| Queer Talk exhibition detail ©Britten-Pears Foundation |

|

| Queer Talk exhibition, detail of timeline ©Britten-Pears Foundation |

This is the background to the exhibition Queer Talk: homosexuality in Britten's Britten which is in The Red House, Britten and Pears' home in Aldeburgh now owned by the Britten-Pears Foundation. In an exhibition space formed from Britten's former swimming pool curator Dr Lucy Walker, director of public programming and learning at the Britten-Pears Foundation, has assembled a small but telling exhibition which relates Britten's experience and works to the attitudes of the outside world.

Key to the exhibition is the juxtaposition of the public and private. All along one wall runs a lively timeline which places events in Britten's and Pears' life against the wider political and social homosexual context, include a line of flags indicating when countries legalised homosexuality. On the opposite wall there is another display, culled from the recent book of Britten and Pears' correspondence (some 350 or so letters). These are more intimate expressions of regard, love and affection, the sort of private slang phrases which any could develops. In a way this is to shine a light on something which they kept very private, and the organisers are aware that there are still people alive in Aldeburgh who knew the couple. But in historical terms Britten and Pears are moving from private people to historical figures, and Dr Walker feels that it is important for people to know Britten and Pears fully.

Two of Britten's works are featured in detail, Canticle 1 and the opera Billy Budd and there is a video which includes excerpts from them, as well as the out gay tenor John Mark Ainsley talking about the canticle, the role of Captain Vere in Billy Budd and Britten's Nocturne.

|

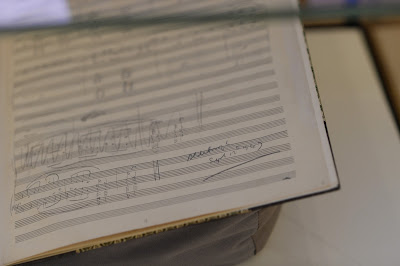

| Detail of Canticle I by Benjamin Britten ©Britten-Pears Foundation |

But a third display case sets this against the lives of Forster himself, Alan Turing and Noel Coward. All three were gay and all three were Britten's contemporaries. Whilst Forster castigated Britten about Billy Budd in the 1950s, he had stopped writing fiction in the 1920s, leaving his homosexual novel to be published Maurice after his death and feeling that if he could not write fiction and be true to his nature then he would write only non-fiction. Ironically, whilst EM Forster was castigating Britten about the 'soggy depression and growing remorse' in Billy Budd, Forster was also sharing his unpublished novel Maurice with Britten and Pears. Being open only went so far.

|

| Queer Talk Exhibition, detail of timeline ©Britten-Pears Foundation |

To provide a suitably corrective backdrop, there is a display about attitudes to homosexuality with headlines from contemporary newspapers, as well as reportage of the Wolfenden Report which led, ultimately to the 1967 bill. Film footage includes Wolfenden talking, but also has excerpts from the film 1961 film Victim which played an important role in changing attitudes, and was in fact the first English language film to use the word homosexual.

The exhibition is one of a number in the UK where organisations such as the National Trust and the National Portrait Gallery are exploring themes arising from the 50th anniversary of the decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales. Queer Talk provides a fascinating insight into the way the political, social and private interwove in Britten's life. The exhibition comes with an excellent accompanying book in which Lucy Walker, Paul Kildea, Neil Bartlett, Justin Vickers, Nicholas Clarke, Andrew Moor and Christopher Rogers explore further the themes from the exhibition. Particularly intriguing is the essay by Neil Bartlett, a famously out performer and activist, talking about his experience directing four of Britten's key works.

The exhibition runs at the Red House until 28 October 2017. There is an associated programme of films at the Aldeburgh Cinema, and study day events at the Red House. As part of the Aldeburgh Fringe during the Aldeburgh Festival, the Red House will be staging a complete reading of the Wolfenden Report.

Elsewhere on this blog:

- Composition is a full on meeting with his Christianity:: I talk to composer Patrick Hawes about his new album Revelation - interview

- Taking them seriously: Gilbert and Sullivan's The Pirates of Penzance at English National Opera - opera review

- Energy and commmittment: Rebecca Miller and the Salomon Orchestra in Kodaly and Bartok - concert review

- O Sing Unto the Lord: Andrew Gant's engaging history of English church music - Book review

- Sui Generis: Karmana from Simon Thacker - CD review

- Stunning technique: Debut recital disc from Aida Garifullina - CD review

- Contemporary wind music from Estonia: Rhapsody for Winds - CD review

- Birthday celebrations: I chat to Nicola Lefanu about forthcoming premieres - interview

- Winter magic: Rimsky-Korsakov's The Snow Maiden in a rare outing courtesy of Opera North - Opera review

- Disturbing video games: Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel from Opera North - opera review

- Vivid theatricality: Suzi Digby and Ora - concert review

- Strong stuff: Chamber music by Kodaly and Dohnanyi - cd review

- Seminal Bulgarian composers: Wind from the East from pianist Victoria Terekiev - CD review

- Home

.jpg)

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment