|

| Elan Sicroff |

This month, April 2021, Nimbus Alliance is releasing five discs devoted to the Russian composer Thomas de Hartmann (1885-1956). All the recordings feature the American pianist Elan Sicroff and are the fruit of The Thomas de Hartmann Project of which Elan Sicroff is a leading figure. If the name of Thomas de Hartmann is known at all, it is likely to be in connection with the Georgian mystic and philosopher George Gurdjieff (1877-1949) with whom De Hartmann had a significant collaboration. But De Hartmann's music encompasses far more than this, and the Thomas de Hartmann Project (of which Robert Fripp is executive director) is specifically aimed at widening the appreciation of the significant amount of music by Thomas de Hartmann which was not written in collaboration with Gurdjieff.

|

| Thomas de Hartmann in the 1950s |

Elan is a classically trained pianist originally with a repertoire that emphasised the continuum of composers from Bach to Brahms. He admits that it was a long process for him to become familiar with De Hartmann's music and to be convinced of its value as initially he thought, as many do, that a composer's music must be unknown for a good reason. One significant moment in his development Elan cites as a performance of Mozart's Requiem in which he took part (as a singer) whilst he was still at Oberlin College. The performance was a direct result of the Kent State Massacre of 1970, and it showed Elan how music could convey extra-musical experiences.

A few years later he came across Thomas de Hartmann's music as a result of his attending the International Academy for Continuous Education at Sherborne in Gloucestershire which was run by John Godolphin Bennett (1897-1974) who was a leading exponent of the teachings of Gurdjieff. Elan would attend the academy as a student and stay on as director of music. Here he was exposed to the music De Hartmann wrote in collaboration with Gurdjieff, consisting of Eastern music arranged for piano. Elan found this repertoire interesting, but it did not supplant the 19th century classics in his affections.

J.G. Bennett got in touch with De Hartmann's widow, Olga de Hartmann (1885-1979) who sent some of the composer's late pieces. These were rather dissonant, and somewhat outside of Elan's experience. But Elan gradually began to work with De Hartmann's music, giving a concert in 1975 at which he finally met Olga de Hartmann. It was the discovery of De Hartmann's Cello Sonata (1941) and Violin Sonata (1936) which were a turning point for Elan. The pieces were just gorgeous, and he found it hard to believe that there was an unknown composer of such value out there. And when he played these works in concerts, the reaction from the audience was good too.

Then in the late 1970s he got the music for some of De Hartmann's early pieces, the Six Pieces (1902) and Trois Morceaux (1899) and these were equally gorgeous. Being early, they showed the influence of De Hartmann's teacher Anton Arensky (1861-1906), yet Elan thought they were works that any pianist would want to put on a programme. And it was only after discovering these early works, that De Hartmann's late style made sense.

Elan has found the music often difficult to memorise, often because the

harmonies are ambiguous and counter-intuitive, and the way De Hartmann

writes the harmonic structure can make the work difficult to pull apart, whilst some of his piano writing is incredibly difficult.

So who was Thomas de Hartmann?

|

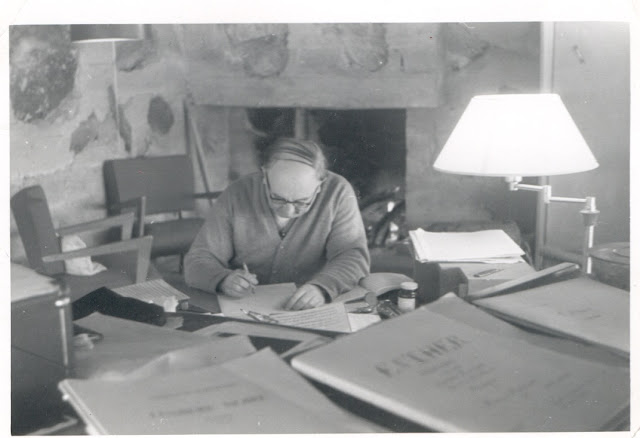

| Thomas de Hartmann working on his opera Esther at Taliesin in Arizona, the home of Frank Lloyd Wright (early 1950s) |

Born in the Ukraine to a family of aristocrats he was something of a prodigy. De Hartmann's roots are important, one great uncle was Eduard von Hartmann (1842-1906) who wrote Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869) which influenced Sigmund Freud, whilst another great uncle was Viktor Hartmann (1834-1873) the painter whose works inspired Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition. Thomas de Hartmann channelled both these men, becoming interested in the psychology of the unconscious, the connection between colour and sound, and music based on painting. Another influence is Russian fairy-tales, and De Hartmann would later describe his life in terms of a quest. Go, no knowing where. Bring, not knowing what.

At the age of 21, De Hartmann became famous in Russia thanks to the premiere of his ballet La Fleurette Rouge by the Imperial Ballet with Vaslav Nijinsky, Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Fokine dancing the leading roles. The success was so great that the Tsar gave him a dispensation which exempted De Hartmann from military service. This was in 1906, and the height of De Hartmann's career, but he did not take advantage of it. Instead, in 1908 he went to Munich to study conducting with Felix Mottl (1856-1911) who had assisted conductor Hans Richter in preparing Richard Wagner's first complete Ring Cycle at Bayreuth in 1876, and himself conducted Tristan und Isolde at Bayreuth in 1886.

But in Munich, De Hartmann found the music scene was very rigid, and he was drawn to other artists. He became a friend of the painter Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and the artists of Der Blaue Reiter school. De Hartmann created works with Kandinsky and the dancer Alexander Sakharov (1886-1963) which became all the rage. This period culminated in De Hartmann's unfinished work Der Gelbe Klang (which was reconstructed in 1972 and premiered at the Guggenheim Museum). But World War I meant he had to return to Russia for military service.

|

| Thomas de Hartmann and his wife Olga at around the time of their wedding in 1906, the year of the premiere of his ballet La Fleurette Rouge |

In 1916 he met Gurdjieff, becoming very influenced by Gurdjieff's teachings. To escape the Revolution, De Hartmann travelled to the Caucasus where he met up with Gurdjieff. There De Hartmann lived for a year in Tblisi, teaching at the conservatory, becoming artistic director of the opera house and meeting the Armenian composer Komitas (Soghomon Soghomonian, 1869-1935). But then the Bosheviks arrived and De Hartmann followed Gurdjieff to Constantinople where De Hartmann created an orchestra of Russian musicians displaced by the Revolution. But civil war in Turkey meant that De Hartmann and Gurdjieff ended up living outside Fontainbleau in France. De Hartmann would remain with Gurdjieff until 1929, not writing any classical compositions but working on ideas with Gurdjieff, adapting the music of the East. This body of works is known as the Gurdjieff/Thomas de Hartmann music and it is very much outside the classical music world.

But in 1929, De Hartmann and Gurdjieff split and the composer moved to Paris. To support himself he wrote film scores under a pseudonym, and it is from this period and after, during World War Two, that De Hartmann's large scale works date including a symphony, his opera Esther and concertos. De Hartmann started to become well known and he premiered his Piano Concerto with Eugene Bigo conducting. But in 1950 the De Hartmanns moved to New York and though some works were performed, he struggled to become known and died in 1956 before really establishing himself in the USA.

So from this, we can see that De Hartmann's life events were rather against his music becoming known, but Elan points out that De Hartmann's output goes through a number of styles, impressionism, jazz, Eastern music, World music, bitonality and modernism. Yet at heart he was a Romantic, which meant that he was often writing music which went against the rather anti-Romantic sentiments of the times he lived in.

|

| Alexander Schneider plays Thomas de Hartmann's Violin Sonata Op. 51 with the composer at the piano, Pablo Casals following the music |

In 1983, Elan heard a lecture on the New Romanticism which talked about the reaction against modernism by such composers as John Tavener (1944-2013) and the American minimalists. And it struck Elan that his might be an opportunity for Thomas de Hartmann's music to become better known. Finally, he was able to start the Thomas de Hartmann Project, creating the recordings between 2011 and 2015. He comments that of all the musicians that worked on De Hartmann's music, only one did not like it and the response of most was 'how could this music not be known'.

The recordings were initially issued in 2016 on a small label, but unfortunately not much was made of the discs and finally in 2019 Elan was able to get the recordings back, and in 2020 agreed on them being issued by Nimbus.

With such a varied output and an eventful life, I was interested to find out how much influence De Hartmann's work with Gurdjief had had on the composer output in the period after he split from Gurdjieff. Elan comments that De Hartmann's style is very much cumulative so that his early sense of Romanticism can be detected even in the late works. There are works, such as the Violin Sonata and the Deux Pleureuse (which were dedicated to cellist Pablo Casals) where the Gurdjieff/Thomas de Hartmann music can be heard, but De Hartmann always gives it sense of being a quotation. As with much that the composer did, there is a subtext. Often De Hartmann is using Gurdjieff's powerful ideas in his later music, not just the works written in collaboration. Also, Kandinsky's theories of colour feed into the music too, creating a philosophical approach which can be applied to music.

This idea of a philosophical subtext can be seen in a work like Six Commentaries on James Joyce's Ulysses. Why was De Hartmann interested in Ulysses? Elan points out that Joyce's use of stream of consciousness in the novel links to Gurdjieff's ideas about associative thinking during meditation and De Hartmann was interested in exploring these ideas in music. So the Six Commentaries link Joyce and Gurdjieff. Whilst the Piano Sonata No. 2 is dedicated to Gurdjieff's poetical ideal of the fourth dimension. Elan sees De Hartmann trying to put Gurdjieff and his ideas into his compositions throughout the 1940s and 1950s.

|

| Elan Sicroff recording Thomas de Hartmann's piano music in 2012 |

There is a significant amount of music, over 90 opus numbers (including the film scores). There are four symphonies, concertos for double bass, harp flute, piano, violin and two for cello. The current release sees five disc of his music being issued, and there are plans for more. Elan hopes to record the piano concerto this year and there are plans for other concertos in the works. Then of course there is the ballet, La fleurette rouge which is a huge work.

The music of Thomas de Hartmann on Nimbus Alliance

The Piano Music of Thomas de Hartmann

(2 CD set) [Amazon]

Trois Morceaux, Op. 4 Nos. 2 & 3 (1899), Three Preludes, Op. 11 (1904), Twelve Russian Fairy Tales, Op. 58 (1937), First Piano Sonata, Op. 67 (1942), Two Nocturnes, Op. 84 (1953), Six Pièces, Op. 7 Nos. 1, 5 & 6 (1902), Divertissements, from Forces of Love and Sorcery, Op. 16 (1915), Humoresque Viennoise, Op. 45 (1931), Lumière noire, Op. 74 (1945), Musique pour la fête de la patronne, Op. 77 (1947), Second Piano Sonata, Op. 82 (1951)

Elan Sicroff piano

The Chamber Music of Thomas de Hartmann - Works for Violin, Cello, Double Bass, Saxophone Quartet and Flute

(2 CD set) [Amazon]

Sonata for Violin and Piano, Op. 51 (1936), La Kobsa (1950), Deux musiques de vielleurs Ukrainiens, Hommage à Borodine Sérénade-badinage (1929), Feuillet d'un vieil album (1929), Fantaisie - Concerto for Double Bass and Orchestra, Op. 65 (1942), Chanson sentimentale (1929), Deux pleureuses, Op. 64 (1942), Koladky, Op. 60 (1942) Ukrainian Christmas Carols, Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, Op. 63 (1941), Four Dances from Esther, (Act III of the opera) Op. 76 (1946), Trio for Flute, Violin and Piano, Op. 75 (1946)

Katharina Naomi Paul violin, Natalia Gabunia violin, Ingrid Geerlings flute, Joris van Rijn violin, Anneke Janssen cello, Quirijn van Regteren Altena double bass, Amstel Quartet saxophones, Remco Jak soprano, Olivier Sliepen alto, Bas Apswoude tenor, Ties Mellema, baritone

The Songs of Thomas de Hartmann - For soprano & piano, and for vocal quartet [Amazon]

Settings of poems by Achmatova, Shelley, Zota, Ronsard, Zhukovsky, Pushkin, Joyce, Moreux & Gual

Three Romances, Op. 5 (1900), Four Melodies, Op. 17 No. 4 - 'Vision of Pushkin', To the Moon, Op. 18 (1915), Morning (1931), Bulgarian Songs, Op. 46 (1931), Three Poems by Shelley, Op. 52 (1936), Sonnet de Ronsard, Op. 54 (1936), Romance 1830, Op. 55 (1936), A Poet's Love - Nine Poems by Pushkin, Op. 59 (1937), Six Commentaries from ‘Ulysses’ by James Joyce, Op. 71 (1943), Pour chanter à la route d’Assise from À la St. Jean d’étè (1948), La Tramuntana, Op. 80 (1949)

Nina Lejderman, soprano

Claron McFadden, soprano

Vocal Quartet Judith Petra, soprano, Anjolet Rotteveel, alto, Alan Belk, tenor, Daniël Hermán Mostert, baritone

Elan Sicroff, piano

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

- A journey to Anatolia through the ears of The Turkish Five, pioneers of western classical music in Turkey - record review

- Charmes: an

alternative century of song from Olena Tokar and Igor Gryshyn with

music by Alma Mahler-Werfel, Clara Schumann, Pauline Viardot-Garcia and

Vitezslava Kapralova - record review

- 60th birthday celebration: Faroese composer Sunleif Rasmussen's works for recorder player Michala Petri survyed in this engaging and imaginative disc - record review

- Music of sundrie sorts, and to content divers humours: Byrd's 1588 Psalmes, Sonets & songs of sadness and pietie in its first complete recording from Alamire - record review

- Bringing audiences into closer contact with the poetry: tenor Ilker Arcayürek on the art of the song recital and his new disc of Schubert songs - interview

- Scholarship and enjoyment combine in Il Gusto Barocco's lovely fresh account of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos - record review

- Proud Songsters: a survey of English song by ten distinguished alumni of King's College, Cambridge on the college's own label - record review

- A Healing Fire: Greek

guitarist Smaro Gregoriadou in music by Bach, Britten, Gubaidulina

& Hetu played on instruments by George Kertsopoulos - record review

- Super-excellent Gabrieli and RVW on viols: National Centre for Early Music's Awaken festival - concert review

- He can chisel a mood from just a few bars: pianist

Peter Jablonski talks about his new disc of music by Alexey

Stanchinsky, and about exploring the darker corners of the repertoire - interview

- A musical microcosm of 2020: Isolation Songbook from Helen Charlston, Michael Craddock and Alexander Soares on Delphian - record review

- From Monteverdi & Cavalli to Abba: Rebirth from Sonya Yoncheva, Leonardo García Alarcón and Cappella Mediterranea on Sony Classical - record review

- Home

.jpg)

I think his. Wife also influenced a lot of Artist in New Mexico.thare Mark Hart.

ReplyDelete