Reviewed by Robert Hugill on 16 March 2022 Star rating: (★★★★)

The striking juxtaposition of two major 20th century Hungarian voices, completely different in style but arising from the same background, in stunning performances

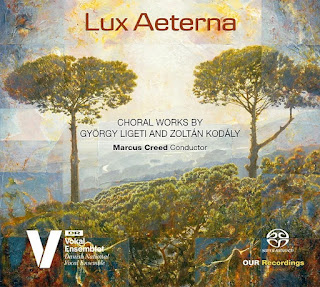

You don't tend to think of György Ligeti and Zoltán Kodály though both were Hungarian and effectively came from the same musical background. A striking new recording, Lux Aeterna, from Marcus Creed and the Danish National Vocal Ensemble on Our Recordings places music by the two composers side by side with Kodály's Matra Pictures and two shorter pieces alongside Ligeti's Lux Aeterna and Drei Phantasien nach Friedrich Hölderlin plus works that he wrote whilst still in Hungary in the 1950s.

Kodály was amongst Ligeti's teachers at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest, afterwards Kodály tried to get Ligeti interested in his ethnomusicological research, but this failed and Ligeti was appointed a teacher of harmony, counterpoint and musical analysis at the academy. Until Ligeti fled to the West in 1956, his knowledge of contemporary Western classical music was limited, though Ligeti did manage to have some modern music sent from Vienna and when he came to the West he was clear where his interests lay, he wanted to explore this new world. The relationship between the two composers was a somewhat tricky one, the Hungary of 1940s and 1950s was very different, culturally and politically, to place where Kodály grew up, and the age difference also caused problems.

The results of Ligeti's explorations of his new world are completely apparent in the shimmering textures of Lux Aeterna where the clouds of notes shift focus but never develop any feeling of impetus. The performance is brilliant and intense, with superb control of the microtonal textures by the singers and the ending, where the cloud of being drifts off into infinity, is magical.

Ligeti's two a cappella choruses from 1955, Night and Morning are perhaps the nearest he came to modernism whilst still in Hungary. Night begins as a quiet, repetitive invocation with opaque harmonies, building to a climax then dying away. It is full of colour and rhythm, though melody and harmony seem less important. Morning is full of vividly intersecting rhythmic lines, and we can sometimes hear the distant inflection of Hungarian folk music.

Folk music is a stronger presence in Ligeti's Songs from Mátraszentimrei from 1955, four folk-songs from the Matra mountains arranged for children's chorus (here sung by the women of the choir). Strong melodies, vivid rhythms and a willingness to place the folk melody against quite a bare background. These are vivid and delightful pieces.

In complete contrast, Ligeti's Drei Phantasien nach Friedrich Hölderlin from 1982 are one of his largest choral works. Written for the Swedish Radio Choir these are complex 16-voiced polyphonic works, though they eschew the micro-tones of Lux Aeterna. The words are almost unimportant, it is the textures that count though Ligeti does also use fragments of motif, near melody. The first is intense, complex and densely wrought, with shifting atmospheres and colours and fragments of high drama. The second is quite, intense and bleak with luminous moments contrasting with opaque harmonies. The final movement is all jagged edges, yet there is tenderness too. The vocal writing throughout stretches both the range and the technique of the singers, and they respond brilliantly.

Kodály's Esti Dal was written in 1938, at first sight it seems quite simple. But the folk-song is in fact sung by a soldier in a foreign country praying to God that he might survive the night, and as such would have had a profound message in 1938. Kodály creates a highly effective setting for the melody, sung with poise and clarity by the choir. Este is a far earlier work, written in 1904 when Kodály and his friend Bartok were just beginning to be influenced by the new French music. It feels highly romantic, but Kodály still places the Hungarian melody at the works fore, developing into something rich and intense, supported by lush harmonies.

Kodály's Matra Pictures dates from 1931 and consists of five movements setting narratives about village life. Everything from a love-sick swineherd who is also a robber, to young lovers, to a young man far from home to a village celebration. The melodies have strong outlines and Kodály's harmonies are haunting, even in the livelier numbers there is a sense of melancholy, and the final song with its vivid evocation of the sounds of village life is a real tour de force from both composer and performer.

The disc has a fine booklet note placing the programme in context, but the texts are just the original languages, you have to go to the record company website to get translations.

This is a fascinating disc, allowing us to see the vivid background against which Ligeti first developed and then rebelled. The two mature voices on this disc could not be more different, yet the programme allows us to see the continuity too. The performances from Marcus Creed and the DR Vocal Ensemble are simply stunning.

György Ligeti (1923-2006) - Lux Aeterna (1966)

György Ligeti - Zwei a cappella-Chöre (1955)

György Ligeti - Mátraszentimrei Dalok (1955)

György Ligeti - Drei Phantasien nach Friedrich Hölderlin (1982)

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) - Esti Dal (Evening Song) (1938)

Zoltán Kodály - Este (Evening) (1904)

Zoltán Kodály - Mátrai képek (Matra Pictures) (1931)

Danish National Vocal Ensemble (DR Vokal Ensemblet)

Marcus Creed (conductor)

Recorded DR Studio 2, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7-8 January 2020, 9-10 September 2021

OURRECORDINGS 6.220676 1CD [50:30]

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Surprising style, elegance and imagination: Auber Overtures volume five - cd review

- Guilty pleasures: Sondra Radvanovsky in the closing scenes of Donizetti's three major Tudor operas - record review

- Having recently recorded Lasse Thoresen's virtuosic cello concerto, I chat to Norwegian cellist Amalie Stalheim about new music, and the continuing importance of the Romantic repertoire - interview

- A room of mirrors: Emiliano Gonzalez Toro, Zachary Wilder and Ensemble I Gemelli - record review

- Bleckell Murry Neet: Traditional tunes from Cumbria in engaging modern versions for guitar and harp - record review

- Black Renaissance Woman: Samantha Ege and John Paul Ekins explore music by six remarkable women from the Chicago Renaissance - record review

- Fun, seduction & politics: Rimsky Korsakov's The Golden Cockerel from English Touring Opera - opera review

- A new opera, an unperformed 19th century opera, plus Weber & Bellini: I chat to Richard Tegid Jones of Rugby-based Random Opera Company - interview

- A joyful celebration of playing together: MiSST's 9th Annual Concert - article

- Urban dystopia: Guildhall School's double bill of Judith Weir's Miss Fortune and Menotti's The Telephone - opera review

- Elan and style: Grands Motets by Michel-Richard De Lalande from Sébastien Daucé and Ensemble Correspondances - record review

- Iceland: The Eternal Music - Graham Ross and the choir of Clare College explore the contemporary music of Iceland - record review

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment