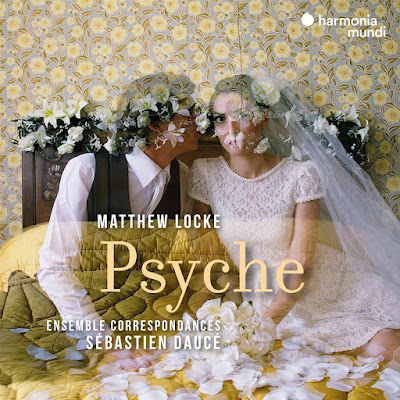

Matthew Locke: Psyche; Ensemble Corresondances, Sébastien Daucé; Harmonia Mundi

Reviewed 9 November 2022 (★★★★)

A lovely recording that showcases Matthew Locke's inventiveness in an imaginative reconstruction of his semi-opera Psyche from French forces, though the English language does not quite have the primacy it needs.

The problem with English opera and music theatre of the 17th century is that so little of it survives. It is difficult to get a good overview when we are reduced to fragments and a few surviving complete works. The score, by Matthew Locke and Christopher Gibbons for the 1653 masque Cupid and Death is the sole surviving score for a dramatic work from that era. Many of the music theatre works were the result of compositional teamwork, Locke was one of the quintet of composers who provided music for The Siege of Rhodes (1656), the breakthrough early opera by Sir William Davenant. Locke wrote music for subsequent Davenant operas, The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru (1658) and The History of Sir Francis Drake (1659). None of these, alas, survive.

After the Restoration, there was interest in music theatre and opera, and there were even attempts to establish opera in London. A French opera company under the direction of Robert Cambert, performed the opera Ariane, ou le mariage de Bacchus at the Drury Lane Theatre in March 1674. Cambert had moved to London with his pupil, Louis Grabu and it was Grabu who adapted the music for Cambert's Ariane and Pomone for London. But the operas were not much to the English taste. For the rest of the century, the English preferred that awkward mixture of speech and music that we now call semi-opera.

Inspired probably by Cambert's French opera, composers Matthew Locke and Giovanni Battista Draghi and librettist Thomas Shadwell collaborated on a new music theatre work, Psyche, with a libretto loosely based on Jean-Baptiste Lully's 1671 tragédie-ballet Psyché. Locke and Draghi's Psyche is arguably the first semi-opera to be created from scratch. It was premiered at the Dorset Garden Theatre, London in 1675. Happily for us, Locke published his music for Psyche, thus enabling performers to try and reconstruct the work.

On a new disc from Harmonia Mundi, the French Ensemble Correspondances, director Sébastien Daucé has recorded the Locke's Psyche, the first major outing on disc (I think) since Philip Pickett recorded it in 1995. Recreating the work is not unproblematic. Thomas Shadwell's word book was published, complete with detailed stage directions, but though Locke published his music that of Draghi has disappeared. It was Draghi who created the dances. Daucé has decided to replace the missing dances with something. Daucé feels that not enough of Draghi's other music survives to be of use, so Daucé has turned to Locke (with piece by Lully) to complete the work.

King Charles II had visited the court of his cousin, King Louis XIV during the Interregnum and seems to have taken a fancy not just to French music (Charles evidently liked music he could tap his feet to), but to the mixed genres of the ballet de cour and the comédie-ballet, which paired music to spoken dialogue and dance. These fitted in with English taste; the strong London theatrical tradition seemed to mitigate against the all-sung opera and the English developed their own genre, the semi-opera.

This means that we struggle to turn the music into a coherent dramatic form, the dialogue is missing and much of the music is in the form of instrumental pieces. Though Psyche is indeed comprised of numerous short pieces, Locke is skilful in the way he builds groups of pieces into coherent scenes. Daucé uses an orchestra of 30 performers with a remarkable range of instruments, and in the instrumental contributions there is so much to enjoy. Locke does not write for a grand orchestra in the modern manner so much as use subdivisions within the ensemble to provide colour and contrast.

Locke's music is richly imaginative and full of variety, he can write lively tunes as much as heart-wrenching ones. Daucé and his performers bring a strong range of colour to the music, mining their experience in French 17th century music to enliven this English cousin. It was to French music that the musicians of 17th century England often turned. Listening to this performance, we can hear how English music of the period fed into that of Purcell, though Locke has his own particular accent.

More problematic are the vocal contributions. Daucé uses an ensemble of soloists who contribute all the solos and join together for the ensemble numbers, like the grand final chorus and dance. The individual soloists all bring considerable style to the performances and bags of character, just listen to Renaud Bres' entry in Act One as Envy, which seems straight out of a Lully opera. Though rather oddly the one bit of Lully used in the recording is sung in Italian, which jars somewhat.

This highlights a particular problem on the recording, few of the singers are able to give us excellent English. Text is important in this music and whilst all concerned work very hard, the range of accents in undeniable. It is possible, William Christie has performed and recorded 17th century English music with singers of a variety of nationalities. But here, the sound and coherence of the English seems to have been less of a concern, and there is a lack of unanimity in the approach.

This is a shame, because Daucé's new version of Psyche is in many ways a delightful confection, lovely melodies, full of invention and superbly sprung rhythms. Above all it demonstrates Locke's wonderful inventiveness and highlights the way Blow and Purcell would draw on his example. We certainly don't have anything like enough Locke in the recording catalogue and for all its drawback this new disc makes a lovely contribution

Matthew Locke (c1621-1677) - Psyche

Caroline Bardot, Étienne Bazola, Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian, Renaud Bres, Nicolas Brooymans, Lieselot de Wilde, Marc Mauillon, Lucile Richardot, Antonin Rondepierre, Caroline Weynants

Ensemble Correspondances

Sébastien Daucé, director

Recorded Chapelle des Jésuites, Saint-Omer (France)

HARMONIA MUNDI HMM 905325.26 2CDs

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- The friendship of Hector Berlioz and Théophile Gautier in song at the London Song Festival - concert review

- Any successful society has music at its core: pianist Iyad Sughayer on his new music academy in Jordan - interview

- Superb musical performances and theatrical dazzle do not quite add up to a satisfying staging of Handel's Alcina at Covent Garden - opera review

- Finally getting the recording it deserves: Meyerbeer's first French opera, Robert le Diable, from Marc Minkowsky, Palazetto Bru Zane and Bordeaux Opera - record review

- Joy and Devotion: Stephen Layton and Polyphony in seven UK premieres including Pawel Lukaszewski's mass dedicated to Pope John Paul II - concert review

- Music for the Moment: Haydn, Fanny Mendelssohn & Jessie Montgomery from the Kyan Quartet - concert review

- A radiant performance from Caroline Taylor as the Vixen lifts HGO's account of Janacek's The Cunning Little Vixen - opera review

- Cross-border cross-pollination: Halévy's opera based on Shakespeare's The Tempest proves to be ideal Wexford territory, if not quite a forgotten gem - opera review

- Musical and dramatic riches: Wexford revives Dvorak's final opera, Armida, in an imaginative production with some superb singing - opera review

- Intriguing work in progress: Alberto Caruso & Colm Toibin's The Master in its first full staging at Wexford - opera review

- Beyond Orientalism: Orpha Phelan's imaginative new production of Félicien David's Lalla-Roukh at Wexford - opera review

- Barbara Hannigan conducts Stravinsky & Knussen as part of a collaborative project between the Royal Academy of Music and the Juilliard School - concert review

- Home

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment