|

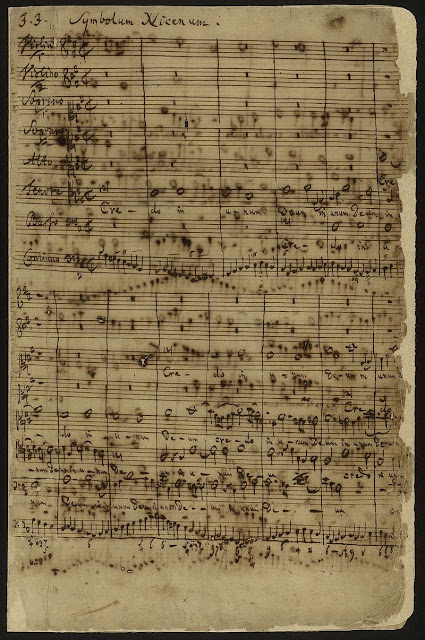

| Bach Mass in B minor - Autograph of the 1st page of Symbolum Nicenum, beginning with the Gregorian chant Credo in the tenor |

Reviewed by Ruth Hansford on Apr 2 2016

Star rating:

A fascinating lecture, and an energetic performance which struggled to find space on a crowded platform

Bach’s Mass in B minor was the centrepiece of the Kings Place Bach Weekend on Saturday 2 April 2016, curated by baroque flautist Martin Feinstein. Professor Timothy Jones from the Royal Academy of Music gave a fascinating lecture in the afternoon, and the performance by the London Bach Singers and the Feinstein Ensemble was in a packed Hall One in the evening.

The main question Jones asked was “Is the Mass in B minor ‘a work’?” He showed how Bach compiled the piece out of some of his earlier successes: the Kyrie and Gloria in 1733 and the Credo in 1748-49; the Sanctus was first performed in a church service but it was not intended for a liturgical context. It certainly explains why it never feels (to me anyway) as a unified work like the Passions, and why there are so many big finishes that invite applause in the middle of the piece – though it is often treated by today’s audiences as a proxy act of worship.

Bach had been the second choice for the post of Cantor at Leipzig, after Telemann. The job was one of teacher (not Bach’s forte) and arranger, but Bach got the job on the strength of his reputation as a court composer, which suited the aspirations of his employers at Leipzig for a while. By 1730 the local politics was beginning to work against him (this was a time when music mattered to politicians as something to be encouraged not bludgeoned to within an inch of its life…) and so Bach made discreet enquiries about Danzig and Dresden. To this end he got together a portfolio of his best instrumental and vocal work with the intention of presenting it to Dresden. He re-arranged material to suit the tastes of his prospective employers, Catholics with a taste for Neapolitan styles and operatic conventions and a roster of virtuoso instrumentalists and singers at their disposal.

Jones talked of Bach as a craftsman, as a canny businessman with an eye for posterity, and as a man of faith. He singled out the Confiteor – one of the few new compositions – as the most impressive movement in the Mass: incredibly complicated on the ear, though fascinating on the page, he speculated that we are not meant to hear every note Bach wrote, rather be overwhelmed by a wall of texture that turns into a labyrinth after the stretto and exploits the ambiguous qualities of the chords. Bach was interested in the musical expression of religious symbols – chaos into resurrection. One might also ask if it was meant to fascinate and flatter the performers as much as impress the employers. Also, more people would have seen the score than listened to a performance – Haydn and Mozart saw the score but Beethoven failed to get his hands on a copy. At the time there was little in the way of a printed music industry – that came later, as did the growth of choral societies to sing these works.

Hence Tim Jones’ assertion that this was not a ‘work’ to be performed, possibly rather a statement from Bach saying “this is how I see myself in the musical history of Europe”. His monument. The lecture did reinforce the sense of the Mass as a problematic piece, not meant to be performed in the way we hear it now and certainly not performed in a liturgical context.

On to the evening and the performance, which in many respects reflected the themes of the talk: the eclectic nature of the piece; the opportunities for individual singers and players to demonstrate their skills as soloists; the internal ‘big finishes’. There was no doubt it was fun and there was a huge amount of energy all round.

There was a difficulty, though: Hall One at Kings Place may well be a miracle of acoustic engineering, isolated from the noise and vibration from outside and crammed cleverly into a tight space with its elegant octagonal shape and stylish interior decoration. But for ten singers and almost 20 instrumentalists there simply is not enough elbow room. There are some optimal places for communicating across the stage and alas not everyone could be in them. The singers turned in towards each other for the sake of the ensemble but the audience lost the sound at crucial moments. The violins seemed to suffer especially from the lack of communication.

Would it have benefited from a conductor? Undoubtedly: it needed someone who was visibly in charge, though an extra person would have added to the problems of real estate on the platform. Above all, the sound, which was at times huge, needed somewhere to go. The voices were predominantly more grown-up and would have suited a more generous space.

Having said all that, it was quite obvious that these are all consummate musicians in their right. They communicated the immense variety of styles and moods: mezzo Clare Wilkinson and alto Tim Travers-Brown negotiated the low coloratura of their arias (the Laudamus te and Qui sedes respectively) and meant each phrase they sang; the bass William Townend was impressive in the Quoniam and his colleague Ben Davies wove sinuously around the oboes Katharina Spreckelson and Hannah McLauchlin in the Et in Spiritum sanctum. Tenor Gwylim Bowen’s plangent duet with Martin Feinstein was charming and the final aria, the Agnus Dei, beautifully still and thoughtful. Some of the smaller ensembles – with fewer instruments – worked well, as did the more rhythmic big choral numbers: the butch Ex resurrexit and the Sanctus with its stunning choral trills.

I would love to hear this done again in a more sympathetic space where the three trumpets, the timps and the natural horn can come into their own, and the problems of balance and communication across the ensemble can be resolved.

Kings Place is a good venue for a ‘curated’ event like this, with its many indoor and outdoor spaces for hanging out with friends, meeting random new people, or sitting with a book. But the in-house caterers missed a trick: they had a captive audience for the day but the staff didn’t seem to know much about table manners. Over-priced sandwich handed over in its wrapping, no cutlery or napkin and the plate handed over separately…? Paper cups for the coffee I guess is the norm, but a real one would be nice. There is plenty of street food around the neighbourhood; Kings Place should complement this with its indoor offer.

Reviewed by Ruth Hansford

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Mass in B minor BWV 232

Kings Place, 2nd April 2016

London Bach Singers:

Faye Newton, Mhairi Lawson, Penelope Appleyard, Angharad Gryffydd-Ones – soprano

Clare Wilkinson, Tim Travers-Brown – alto

Nicholas Hurndall-Smith, Gwilym Bowen – tenor

Den Davies, William Townend - bass

Feinstein Ensemble:

Catherine Manson, Miki Takahashi, Elizabeth McCarthy – violin

Jane Norman – viola

Christopher Suckling – cello

Kate Aldridge – bass

Martin Feinstein, Michaela Ambrosi – flute

Katharina Spreckelson, Hannah McLauchlin, Leo Duarte – oboe

Andrew Watts, Nathaniel Harrison – bassoon

Anneke Scott – horm

David Blackadder, Philip Bainbridge, Matthew Wells - trumpet

Robin Bigwood – organ

Bob Howes - timpani

Lecture by Prof Timothy Jones

Elsewhere on this blog:

- Smooth and intimate: The Kings Singers in Palestrina - CD review

- Engaging and playful: Bach Goldberg Variations - concert review

- Poetic Liszt: Praxedis Genevieve Hug in lesser known Liszt transcriptions - CD review

- Hidden in plain sight: A brief survey of LGBT relationships in opera - Feature article

- 70th birthday retrospective: Trevor Pinnock's engaging Journey - CD review

- Vivid & intense: Pop-Up Opera in the round in Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi - Opera review

- Bonkers fun: Gerald Barry's The Importance of Being Earnest - Opera review

- Evocative & engaging: Elena Langer's Landscape with three people - CD review

- Dublin version: Handel's Imeneo - CD review

- The Shepherd on the Rock in context: Music by Schubert his contemporaries from Elena Xanthoudakis - CD review

- Simply remarkable: The Passion from Streetwise Opera and The Sixteen - Opera review

- Trying a bit too hard? Saimir Pirgo Il mio canto - CD review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment