|

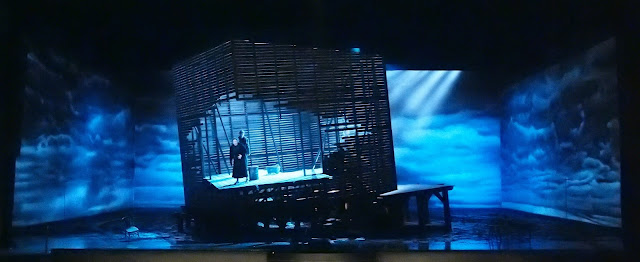

| Elysium - Den Norske Opera. Directed by David Pountney. Set and costume design by Leslie Travers - photo Erik Berg |

|

| Elysium - Den Norske Opera. Directed by David Pountney. Set and costume design by Leslie Travers - photo Erik Berg |

Incredibly ambitious

We started by talking about the Grange Park Opera production of Verdi's Don Carlo, which is being directed by Jo Davies. This will be the first time Leslie has designed this huge piece, and it is incredibly ambitious to fit Verdi's demands into the Grange Park theatre especially as the opera requires such a sense of scale in the designs, and Leslie finds that Verdi demands that with each scene change you jump directly into the next scene. He and director, Jo Davies, have decided to deliver all the different spaces Verdi expects, rather than using a single set.

Here Leslie brings up something which he comes back to a number of times in our discussions, the sense of scenic development in the piece and the way there is a sense of movement between scenes. I get the impression that Leslie is as interested in what happens between scenes as in the scenes themselves. It is clear that some thought has gone into it. The great Auto-da-fe scene happens just before the interval, so the rest of the design needs to work forwards and backwards from there. Leslie's designs use clever elements which are adaptable, and some of the scene changes are choreographed so they become part of the theatrical experience, which also removes the need for endless pauses. When we talked, they had just done the piano dress rehearsal and Leslie was happy that they had showed that all the changes could be achieve in time.

The design side of an opera is something of a mystery to most people

|

| Leslie Travers - photo Catherine Morgan |

For Don Carlo (which is being performed in the four-act version), the work opens with a funeral and Leslie feels that everything comes out of that architecture. He has brought a sense of scale and mass to the designs, using an abstracted essence of the architectural elements like the cathedral, rather than literal realism.

He immediately knew that he wanted to do something in the theatre

Leslie grew up in Hartlepool in NE England, where his experience of theatre was mainly restricted to what he saw on television. But as when he was 11 he saw the Royal Shakespeare Company performing in Newcastle and immediately knew that he wanted to do something in the theatre. At the time he was so convinced by the theatrical world conjured up on stage that he did not understand it as design. It was only in his later teens that he discovered theatre design, particularly with the work of designers like Stefanos Lazaridis and Nicholas Georgiadis. And for the young Leslie the most exciting designs for those for opera because of the sense of scale of the works and through the combination of the music. He was very single-minded in his educational choices, ultimately training at Wimbledon College of Art.

More of an education than work

But on leaving college Leslie admits he was unprepared for the outside world. He worked for a time in the model room at Covent Garden, and assisted a number of designers ultimately assisting Yolanda Sonnabend. His time with her was more of an education than work, as she taught him what he did not know including remedying his musical education. She would play music to him every day and test him on it! He also worked with other designers, not only learning how they worked but how they dealt with difficulties, thus he learned that it was one thing having ideas but it was quite another making them a reality on stage.

|

| Jenufa - Malmo Opera . Directed by Orpha Phelan. Set ands costume design by Leslie Travers - photo Leslie Travers |

Co-production also means producing designs for theatres with different technical setups and different degrees of sophistication in the theatrical machinery. This Leslie does not find limiting because he tends to avoid automation as it can go wrong and he usually relies simply on man power.

Verdi seems to expect the scene changes to happen by magic

Our discussions return to the subject of scene changes, which for Leslie should be part of the story. He is always careful to ensure that there are never any moments when the audience sees something that they should not be looking at. He is currently designing a production of Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro for the USA and the production will have no pause between Acts One and Two, and no pause between Acts Three and Four, something Leslie has found improves the momentum. For him it seems to make the piece seem shorter, with pauses the performance loses energy. This is something that he and Jo Davies have been careful to consider in the production of Don Carlo, ensuring the performance does not lose momentum. Though he admits that Verdi does rather make a challenge for the designer as Verdi seems to expect the scene changes to happen by magic.

|

| The Marriage Of Figaro - Opera North - Directed by Jo Davies. Set and costume design by Leslie Travers. Photo - Clive Barda |

As the production of The Marriage of Figaro will be travelling to four American cities, Leslie comments that it is going to be in his life for a long time as he will be present each time the production moves to a new house. He refers to this as 'such fun' and says it is quite surprising how the design for the house comes into life. He anticipates that he will be adapting the costumes for the different casts, and is concerned to take into account the different singers' personality and voice. He notes who has been cast and takes account of that, so that his costume is not imposing itself on the new singer.

Peter Grimes on the Beach

In the Autumn he will be designing Britten's Billy Budd for Orpha Phelan's production at Opera North, which will reunite Leslie with the tenor Alan Oke (who plays Captain Vere), and who sang the title role in the production of Peter Grimes on the beach at Aldeburgh. This was quite a brief, as the audience sat on the shingle of Aldeburgh beach and experienced the vagaries of the weather and the wind, whilst Leslie's brief was to design something against the sky which Britten had looked out at. There was also the simple thrill of taking Peter Grimes to Aldeburgh.

But you can't control the weather and for the first night there was a freezing North-East wind so that there was a genuine anxiety that the audience would leave because it was so cold. Instead a dogmatic British spirit came into play, and all 3000 stayed; there was no noise, just intense concentration. At the second performance it was foggy, 'like Götterdämmerung' and there was anxiety that the audience would not be able to see the show. On the third night, the weather evoked the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich and during Grimes' Pleiades aria the clouds parted and the result was simply magical.

The production was Leslie's first Peter Grimes and his colleagues thought he was 'crazy to do it' and that it would be a disaster, but for Leslie it was exciting because of the risk. Leslie found director Tim Albery superb in the way he handled the performance's unique problems and made it all possible. Leslie has never done Peter Grimes in the theatre and would love to do it; now he feels that enough time has lapsed, and he would see the piece in a different way. In the theatre the rules are different. But designing for the performance on the beach gave him an ambition for the piece and he would love to do it again.

'The pieces you should do are the ones that you don't like'

I was curious as to whether Leslie had favourite pieces, but he tries not to. In fact David Pountney gave him some advice saying that the pieces you should do are the ones that you don't like. And generally Leslie finds that he falls in love with a piece eventually.

|

| I Puritani - Welsh National Opera - Directed Annilese Miskimmon, sets and costumes by Leslie Travers photo Robert Workman |

Around 85% of his work does not leave the studio

I was interest also to find out what Leslie thought was the trickiest production to design, but he retorted that they were all tricky. He has recently designed two operas on vastly different scales, the grand Don Carlo for Grange Park Opera, and the premiere of Mark Simpson's Pleasure, a small scale piece performed and toured by Opera North. But for Leslie, despite the differences in scale, both required the same process and he feels you need to challenge your own work each time. He is quite brutal, ensuring he scrutinise properly the choices made, and why they were made.

|

| I Puritani - Welsh National Opera - Directed Annilese Miskimmon, sets and costumes by Leslie Travers photo Robert Workman |

With repertory pieces like The Marriage of Figaro or Don Carlo, Leslie has existing performances and recordings to fall back on to help get to know a work. But he tries to forget about productions he has loved and seen whilst doing the designs, though once a design is together he finds it interesting to see how others have solved the problems. The biggest problem is in seeing a production which is so wonderful and you need to forget it, and solve the problems yourself.

With new pieces it is far more a journey into the unknown

But with new pieces it is different, and he has just done two new pieces back to back; Mark Simpson's Pleasure at Opera North, directed by Tim Albery and Rolf Wallin's Elysium at Den Norske Opera, directed by David Pountney. With new pieces it is far more a journey into the unknown, and both pieces were incomplete when Leslie started work. For Elysium he was able to attend music workshops two years ago, which was his only chance to hear the music even though the piece altered substantially subsequently. Whole sections of the opera relied simply on Leslie talking through the work with the composer. But he finds it exciting to be involved in the conception of a new work. And this gives him the luxury of questioning the composer and librettist's choices, and also to be able to let them into his world. So that librettist and composer were involved in the visual development of the work in a way which they had not expected.

|

| Elysium - Den Norske Opera. Directed by David Pountney. Set and costume design by Leslie Travers - photo Erik Berg |

Each production throws him into somewhere new

Leslie does not think he has a particular style. He tries not he have prejudices, or to impose what he does on the director. Each director has a different process of working, and each production throws him into somewhere new. Elysium had a hard, high-tech feel whilst the forthcoming The Marriage of Figaro is abstract and lyric. But though he doesn't feel he has a house style, he admits that there are connecting elements. And it is not just the look, how the sets work is part of the narrative.

Regarding favourite theatres, he has loved working for Opera North, and finds them a great company, doing a huge range of work, with a lot of talent in the company. He has got to know them well and they have been supportive of the design process. At the age of 22, Opera North was the first company he saw outside London. Den Norske Opera in Oslo were also highly supportive of the design work for Elysium. It was Leslie's first job there, and the set and costume department really took on the challenge in a detailed and appropriate way, making it a really exciting journey.

Regarding his desert island works, Leslie would love to direct Wagner's Die Meistersinger and feels that he is now ready for Wagner. Doing Britten's Billy Budd is fantastic, and of course he would love to design Peter Grimes again. With Britten he finds it so hard to pull away from the music as it is so sophisticated.

Elsewhere on this blog:

- Master storytelllers: Robin Tritschler and Graham Johnson in Schubert - concert review

- Terrific celebration: Three large works by Colin Matthews - CD review

- Iconic but inconclusive: Mariella Devia at Rosenblatt Recitals - concert review

- Poetic rhetoric: Schumman's Cello Concerto - CD review

- Notes from the Asylum: Clare McCaldin in Stephen McNeff - Cd review

- Listening for silence: Steven Osborne in George Crumb and Morton Feldman - concert review

- Forty parts for forty years: Graham Ross & choir of Clare College, Cambridge in Tallis, Striggio, Swayne at Spitalfields Festival - concert review

- More than just Crucifixus: Antonio Lotti from Ben Palmer and the Orchestra of St Paul's on Dephian - Cd review

- Funny & filthy: Die Dreigroschen Oper at the National Theatre - theatre review

- Capturing hearts again: Ermonela Jaho's Zaza on disc with Opera Rara - CD review

- Richly imaginative: Mascagni's Iris at Opera Holland Park - Opera review

- Visions of lost worlds: Anne Schwanewilms on Schubert, Schreker and Korngold - CD review

- Home

%20TallWall%20Media_Oxford%20Song.jpg)

%20TallWall%20Media_Oxford%20Song.jpg)

%20TallWall%20Media_Oxford%20Song.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment