|

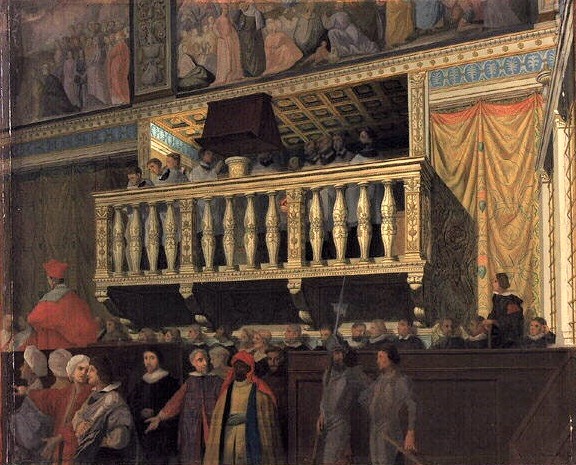

| The choir loft of the Sistine Chapel in the early 17th century (1848 copy by Ingres of a painting by Agostino Tassi) |

Inspired by the Sistine Chapel; Palestrina, Morales, Festa, Carpentras, Allegri, Josquin; The Tallis Scholars, Peter Phillips; Cadogan Hall

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on 26 January 2022 Star rating: (★★★★)

Music by Palestrina and his contemporaries showing off the richness of the treasures performed by the Sistine Chapel Choir

A whole host of musicians worked for the Sistine Chapel Choir, leaving a wealth of music that was written specifically for the choir. Often not well known, because the manuscripts were jealously guarded by the Popes, this is a repertoire usually known simply for a few highlights. At Cadogan Hall on Wednesday 26 January 2021, the Tallis Scholars and Peter Phillips presented Inspired by the Sistine Chapel, a programme of music written for the Sistine Chapel Choir. At the centre, of course, was the famous Miserere by Gregorio Allegri (c1582-1652), but there was also a wide selection of music from masses by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594), plus motets by Cristobal de Morales (1500-1553), Costanzo Festa (1495-1545), Elzear Genet (Carpentras) (c1470-1548), and Josquin des Prez (c1450/55 - 1521).

Running through the evening were a sequence of mass movements by Palestrina, all from masses written for the Sistine Chapel and showing the remarkable breadth and imagination of the composer's style, so we heard from Missa in te Domine speravi, Missa Tu es Petrus, Missa Papae Marcelli,, Missa Confitebor tibi Domine and Missa Brevis. All five movements were richly textured, the first three masses being six-part, the fourth being double choir and the final one, though four-part, adds a fifth voice in the second statement of the 'Agnus Dei'. And this was true of the motets too; the chapel choir might not have been large but they certainly seem to have relished richly written music and of course, the Allegri Miserere is written for ten independent parts.

We began with the Kyrie from Palestrina's Missa in te Domine speravi based on the very popular motet of the same name by Lupus Hellinck (1494-1541), which rather interestingly is thought to have been inspired by the prison writings of the martyred reformer Girolamo Savonarola. Palestrina's music was in many ways typical of the composer's style, beautifully crafted with polyphony that flowed with apparent ease, a gorgeousness of texture with a relish for multi-voiced complexity yet also clear and direct. And we had a rather beautiful Christe section with just four solo voices.

A motet by Morales came next; his Spanish nationality probably was an advantage under the sequence of Spanish popes at the period. His setting of Regina Coeli was vigorous with a strong rhythmic feel and a joyous textures. The Gloria was taken from Palestrina's Missa Tu es Petrus, based on the composer's well-known (today) motet, Tu es Petrus; a very apt text for a choir singing at the heart of the Papacy. The music's debt to the lovely motet was clear, you could hear it throughout, but the Gloria was in fact quite steady and sedate, with Palestrina using rhythm to enliven the text.

Costanzo Festa is not a well-known name, and he was one of the first Italian polyphonic composers to achieve renown. His motet, Quam pulchra es, setting words from the Song of Solomon, was sung by just four voices (SSAT) with no conductor. It received a poised performance, with lovely transparent textures and long intertwining lines. This was followed by a setting of Lamentations by the French composer Carpentras (Eleazar Genet). Carpentras had two stints working in the Papal Chapel, and when he returned for his second one he found that his music was still being performed, but in 'bastardised versions' so corrupted that he hardly recognised them, and he promptly published his music. His Lamentations, for six voices (with no sopranos) were sober and dark, with the polyphony enlivened by rhythmic vigour and the use of open intervals hinting at the relative earliness of the work. A terrific piece.

We ended Part One with the Credo from Palestrina's Missa Papae Marcelli, a richly textured six-voice mass that reputedly demonstrated that polyphony could include clarity of text (something the Council of Trent was keen on). The Credo was vigorous and direct, the words very clear. Even during moments such as 'Et incarnatus est' there was nothing showy about this music it was just finely crafted.

We opened Part Two with Allegri's Miserere. A work that, like Carpentras' Lamentations, would hardly be recognised by the composer if he had returned. Musicological work has revealed what Allegri's original might have been, but during the centuries this became overlaid with the ornamental lines beloved of the singers of the Chapel Choir. Errors in transmission mean that the version of Allegri's Miserere that is traditional today, the one with the Top C, is a long way from the original. But there is no doubting the music's effectiveness, and it received a finely crafted performance from the choir.

Whilst the sound-world that this piece conjures is a boy's voice rising aetherially above a choir of men and boys in an echoing church acoustic, the reality for much of the 18th and 19th centuries would have been very different. The top line (no top C but still high) taken by a mature, highly trained solo soprano castrato keen to show of his prowess in elaborate quasi-operatic ornaments, accompanied by a small ensemble, probably one singer to a part, and in a rather dry acoustic. The Sistine Chapel during the great period of the choir had all the lower walls hung with tapestries, so it is thought that the acoustic would have been rather dry! So, hearing the work sung one to a part by a group of mature adult voices in the sympathetic but dry-ish acoustic of Cadogan Hall was thus surprisingly authentic.

To follow this came the sumptuous Sanctus and Benedictus from Palestrina's Missa Confitebor tibi Domine, using eight voices to very rich effect with gorgeous textures contrasting with dancing Hosannas. Then came Josquin's Praeter rerum seriem, a motet that started with dark, sober music for the lower voices and developed into something sober and intense. As the music progress, Josquin changed the metre, but throughout the music was wonderfully striking.

Inter nos mulierum may or may not be by Josquin. It is attributed to him, but all the sources are late and it may well have been written by another poor composer associated with the Vatican and now lost to history. But the music had gorgeous richness to it that made it memorable.

We finished with an Agnus Dei from Palestrina's Missa Brevis, though in fact there is nothing little about the mass. Written for four parts and familiar to many singers, Palestrina brings in a special moment in the second statement of the Agnus Dei when he introduces a second soprano part in canon with the first. A poised, balanced performance that was pure magic.

The enthusiastic audience was treated to an encore, not from the Sistine Chapel this time - Purcell's Hear my prayer.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I'd be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- The Irish Double Bass: Malachy Robinson goes on a personal odyssey - record review

- Love, jealousy, death and a wedding: Handel's Aci, Galatea e Polifemo from Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment - concert review

- You have two ears and an opinion: artistic director Fiachra Garvey introduces this year's Classical Vauxhall festival - interview

- Decadence and refinement: Karina Canellakis conducts Scriabin's Poem of Ecstasy with the London Philharmonic Orchestra - concert review

- Winter Opera St Louis educates as it entertains - guest posting

- Pure joy: ECHO Rising Star recorder player Lucie Horsch & lutenist Thomas Dunford in music old & new - concert review

- Beyond Miss Julie: Joseph Phibbs on his opera Juliana setting Laurie Slade's updating of Strindberg - interview

- Opera scenes from the Young Artists of the National Opera Studio with the orchestra of English National Opera at Cadogan Hall - concert review

- Beauty and bleakness: Douglas Knehans' Cloud Ossuary from Brno Philharmonic Orchestra and Mikel Toms - record review

- The Art of Transformation: inspired by a Scottish Border ballad Alastair White's Woad is very much an opera for our times - record review

- A sense of ritual: Edward Jesson's Syllable, a work of complex musical theatre, is premiered by Trinity Laban Opera - opera review

- Still in cracking form: Verdi's Nabucco returns to Covent Garden - opera review

- Home

No comments:

Post a Comment